When most people think of Galicia, the first thing that comes to mind is pilgrims walking the Way of St James to Santiago de Compostela. If you are a sailor, you might also think of the blue water crews who have just crossed the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic Ocean and who make one or more stopovers here in the far north-west of Spain.

But the area near Finisterre, the end of the world, as the Romans once called the peninsula jutting out into the sea, is also a worthwhile destination for owners and charterers. It is certainly one of the most beautiful, protected and unspoilt sailing areas in Europe and is neither overcrowded nor overpriced.

The Galician coast

In cultural terms, Galicia only belongs to Spain to a limited extent. The region is Celtic in character, similar to Brittany. The national musical instrument is the bagpipe! People have always sailed from Scotland via Ireland and Cornwall to Brittany and on to Galicia. And back again. That connects them!

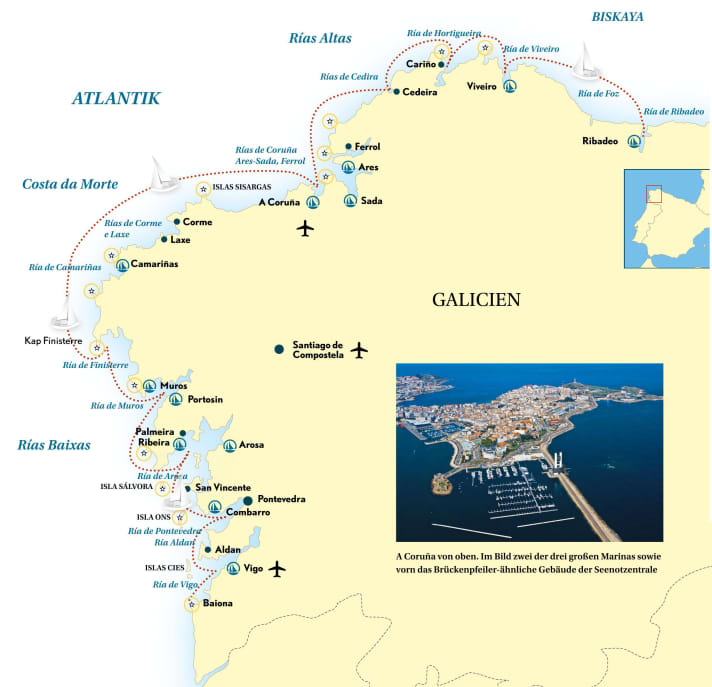

Sailors will find a varied sailing area along the rugged coastline. Here are the rías that cut deep into the land, offering perfect protection and therefore ideal for family sailing trips. Then there is the Atlantic, which constantly rolls in from the west and gives you a good idea of ocean sailing. There are numerous attractive destinations within a short distance between Bilbao and Vigo. In most cases, you sail from one estuary to the next. In the north, the distance from Bilbao to A Coruña is 260 nautical miles, in the west from A Coruña to Vigo less than 120 miles.

The shipbuilding and fishing city of Vigo, with just under 300,000 inhabitants, and the industrial metropolis of A Coruña, 150 kilometres to the north, with 250,000 inhabitants, are also the two largest centres in the region. Santiago de Compostela, the capital of the autonomous community of Galicia, has a population of just under 100,000.

Sailors are very welcome in Galicia

In addition, countless picturesque fishing villages adorn the coast, some of which are still unspoilt by tourism. This in turn is characterised by green, pine-covered hills, at the foot of which sandy beaches appear again and again.

As a holidaymaker, but especially as a sailor, the locals give you a friendly welcome, just like in the old days. Nobody needs to fear tourist rip-offs here, the dinghy is always left unlocked on the jetty. The other holidaymakers you occasionally meet are usually Spaniards from other parts of the country. They like to flee the heat inland to the Galician coast in summer and enjoy the much more pleasant temperatures here.

This is also the reason why the region is still spared from mass tourism: sunshine is not always guaranteed and the Atlantic is not particularly warm here due to the southerly current caused by the Portuguese north wind. The bathing temperature rarely climbs to 22 degrees.

The sailing area of Galicia is a paradise for beginners

Thanks to the current and the continental shelf just a few dozen miles away, where the water depth quickly increases to several kilometres, fresh cold water is constantly flowing in from the depths of the Atlantic. So it sometimes takes a little effort to hop overboard at the anchorage.

Unless you have travelled to one of the rías. In some of them, the water can warm up a little more. Above all, however, you are usually well protected in the narrow bays, which are often surrounded by rocks. On the north coast, in the area around A Coruña, these are the Rías Altas. You then sail along the Costa da Morte, past Cape Finisterre as the westernmost point. Shortly afterwards, the popular Rías Baixas between Finisterre and Vigo, which cut deep into the interior, are reached.

The fjords of Spain, as they are also known, are something of a sailing paradise for beginners and all those who prefer relaxed, short, sheltered stretches from one fishing village to another. Cape Finisterre offers general protection from waves and wind, shielding the coast behind it from the swell of the Atlantic. At the same time, this landmark at the end of the world represents the only major navigational challenge.

A Coruña is the perfect starting point for sailing trips

Coming from the north, it is usually pleasant sailing. The north-easterly wind blowing along the Costa da Morte invites you to leave mile after mile in the wake under genoa alone on a rough course. However, if you want to head in the opposite direction from the Rías Baixas back to A Coruña, it is better to wait for calm weather. As a rule, this means motoring northwards with little wind and swell. Unless, for once, a westerly breeze materialises.

A Coruña is per se an ideal starting point for varied cruises in the region. The city lies at the entrance to the Golfo Ártabro, which is divided into three smaller rías: the Ría de Coruña, the Ría de Ares-Sada and the Ría de Ferrol. Together, they are perfect for short detours from the city into beautiful nature.

At the world's oldest lighthouse still in service, the "Hercules", we continue to the Costa da Morte. Many sail purposefully to Cape Finisterre and then head for the sheltered Rías Baixas. However, they miss out on some of the highlights of the "Coast of Death". Because even here, on the dramatically jagged and cliff-lined shores, two wonderfully charming rías wind their way inland. On their banks are small towns and numerous anchorages.

Dangerous shallows at Cape Finisterre

You can also anchor south of the small Isla Sisargas and then take a trip to the island, which is only populated by seagulls. But beware: once the chicks have hatched, the otherwise peaceful birds become quite aggressive.

Strictly speaking, the Way of St James ends at Santiago de Compostela Cathedral. However, many traditionally continue their journey to Cape Finisterre, where they throw their hiking boots into the Atlantic. At the far end of the headland, however, sailors don't have to watch out for flying shoes so much as a shoal that needs to be avoided. Rumour has it that it grows from year to year - because of the many hiking boots.

There are some nice anchorages and a small, free floating jetty in the nearby Ría de Finisterre. The village of Finisterre and the short walk to the lighthouse of the same name are nice, albeit quite touristy. After all, Finisterre and Santiago de Compostela are the only two places that are visited by large numbers of non-Spanish tourists. The weather in the Ría Finisterre is also determined by the weather conditions in the Rías Altas and on the Costa da Morte. It is therefore usually a few degrees cooler here than in the Rías Baixas.

Galicia and its countless rías

The two fishing villages of Muros and Portosin make up the Ría Muros, with Muros being the more picturesque. Portosin has better direct connections to Santiago de Compostela airport and is therefore an ideal harbour for a crew change.

To get from the Ría de Muros to the next Ría called Arosa, you can either sail around the island of Sálvora completely or - if you're not afraid of archipelago sailing and fancy a bit of a thrill - take a shortcut through the rocks: The Canal das Sagres leads right through the shallows and is therefore orca-safe, not least in late summer.

When there is a swell from the Atlantic, the waves break spectacularly around the ship, while the navigator tries to do the same as the local fishermen and skilfully steers between Sálvora and the mainland. The island is one of three nature reserves. Anyone wishing to anchor or go ashore in front of it must first obtain a general permit and then a specific permit for the day in question. The information can be found on the Website iatlanticas.es.

Has an incredible amount to offer: the largest estuary in Galicia

The Ría Arosa is the largest in Galicia, dotted with countless anchorages, villages and small towns. The many restaurants offer fish, squid and mussels at very reasonable prices. Don't miss the pimientos de Padrón from the Galician town of the same name: small mini peppers fried in salt. They can be accompanied by the Estrella Galicia beer brewed in A Coruña or white wine made from the Albariño grape in the region.

Then, perhaps with a stopover in the enchanting village of San Vicente, we head into the next estuary. The water in between is calm, as it is also shielded from the Atlantic: The offshore Isla Ons, which is also protected, acts as a natural breakwater.

And here, too, you need the same authorisation to enter the island as for Isla Sálvora. However, as the anchorage drops off quickly, a visit is only recommended if you have a very long anchor chain on board. And it is best to leave the spot before nightfall.

The Ría Aldan is an absolute insider tip

It is better to sail into the Ría de Pontevedra and either anchor off Combarro at the very end or moor at the guest jetty there. The typical stone-built granaries resting on pillars with millwheel-sized stone plates are dotted around like little houses in the gardens. This prominent design prevents rats from finding the grain. Although the rodents can climb vertically up the stone pillars, they cannot get any further into the granary upside down.

A stroll through the historic village is always worthwhile, especially as sardines and squid are cooked on wooden grills right by the water.

The small Ría Aldan lies at the southern end of the Ría de Pontevedra. Unlike the large rías, it does not extend eastwards, but southwards into the country. As it collects the water flowing southwards like a cone, it can warm up considerably. This is why the Ría Aldan probably has the highest bathing temperatures. And although it is open to the north and therefore to the main wind direction, you can anchor in its apex in a sheltered spot. For some inexplicable reason, the waves are not reflected here. All in all, an insider tip for Galicia sailors!

Mussels also thrive in the clean waters of the rías. However, sailing is allowed between the breeding centres

Between the estuary of Pontevedra and the southernmost estuary, the estuary of Vigo, lies the third protected island that is well worth a visit! It is the Isla Cíes, for which you also need a permit. You should definitely get one, the island is so beautiful that it is not missing from any brochure about the region.

Off the long sandy beach, the anchor holds well on the sandy bottom. The dinghy then heads for the shore via a channel marked with red and green buoys. Pull the dinghy far enough ashore if the tide is still rising. A wonderful walk to the lighthouse is then almost compulsory. From there you can enjoy an almost intoxicating view over the Rías Baixas.

If you have caught a day with some swell and therefore don't want to stay overnight off Isla Cíes, no problem, Praia de Barra is just opposite. This stretch of beach, which is frequented by nudists during the day, is always quiet when the wind blows from the north. And by the evening at the latest, the sailors are also among themselves here.

The end of the cruise does not mean the end of the world

Finally, there is the southernmost estuary, that of Vigo. At its very centre, it opens up into a huge lagoon just outside the city gates. The neighbouring, much smaller Baiona is particularly attractive. There are two marinas and a large, beautifully situated anchorage. Baiona is best known for the fact that Christopher Columbus' smallest ship, the "Pinta", was the first to make landfall here after his first voyage to America in 1492. It was therefore the inhabitants of Baiona who were the first Europeans of modern times to learn of the continent on the other side of the Atlantic. Today, a replica of the "Pinta" adorns the harbour.

The cruise along the coast of Galicia from estuary to estuary ends here, but the world - contrary to what the Romans believed - does not. Crews exploring the area on their own keel are drawn further along the coast of Portugal. Or in the opposite direction across the Bay of Biscay to France. Charter sailors bring their boat back to base and then return home by air. For some, however, it will certainly not be a farewell forever.

6 tips for the perfect Galicia cruise

1. arrival

On its own keel, Galicia is an ideal holiday destination for anyone who wants to move their boat to the Mediterranean. Or who are travelling to the Canary Islands. Around 1,000 nautical miles lie ahead of you from Germany. Spread over three sailing summers, these are feasible distances. The English Channel and the leap from Brittany across the Bay of Biscay to A Coruña are challenging. Alternatively, you can sail along the coast of western France and northern Spain.

2nd charter

The range of rental yachts is manageable. There are charter companies in Vigo, Sanxenxo and Baiona. There is also an RYA training centre in Baiona (juliovernenautica.com/en). The area is easy to reach by plane; there are three airports in Galicia.

3. orcas

Killer whales that target the rudder blades of sailing boats also make the headlines off Galicia. As a rule, the animals do not appear on the coasts of Galicia on their way north until August. From October onwards, they head south again and pass through the region a second time. So if you sail in Galicia before mid-August, you probably won't see any orcas. After that, it is better to sail close to the coast, even if this means taking a diversion. The whales have not yet turned up in the shallow rías.

4. navigation

The area does not pose too great a challenge to navigation skills. The only thing to watch out for are the wooden rafts of the mussel farms. You can sail between them. Anchorages are often found in front of long, empty beaches. The bottom is often sandy. Pay attention to the tidal range when anchoring. It is up to four metres. The tidal current, however, is negligible.

5. weather

The forecasts for the sea area are reliable; the weather is determined by the Azores High and the low pressure system over the Iberian Peninsula, which is stationary in summer. In summer, the wind usually blows from the north during the day and calms down in the evening. The air temperature reaches 25 to 28 degrees Celsius, dropping to 20 to 22 degrees at night. Unlike on the Mediterranean coast, cloudy or rainy days are not uncommon on the Galician coast, even in summer. When the wind shifts to the south-west, warm, humid air is transported from the Atlantic to Galicia. There it cools off the coast, causing fog to form.

6. literature & maps

- Standard cruising guide "Atlantic Spain and Portugal" by Henry Buchanan, Imray-Verlag, 55 euros

- Very detailed information about the area is available online from local sailor Pablo Veloso Garcia at galiciasailing.com

- Good nautical charts from NV-Verlag: "Atlas ATL1 - English Channel to Vigo", 75 euros