The crew of four young Frenchmen will never forget 1 November 2022. They were sailing three hours west of the Spanish-Portuguese northern border when a brutal bang shook the yacht at around 10.30 in the morning. "Orcas," thinks Augustin Drion. He takes it calmly at first. "They just play around for a few minutes and then disappear again," says the 29-year-old marine biologist.

The crew switches off the engine and instruments, as urgently advised by the Spanish authorities. But instead of calming down, the killer whales, including a young one, attack the sailing yacht more and more aggressively. Augustin slowly becomes uneasy about the orcas' behaviour as they repeatedly ram the rudder blade and shake it with all their might.

Suddenly, he hears the cracking of bursting material below deck. As he and the skipper rush inside the ship, there is an 80-centimetre-long crack in the hull aft of the rudder coker. Seawater gushes into the stern bunk while the whales work the rudder a hand's breadth below them.

A video taken by the crew at 12.05 p.m. shows water sloshing over the saloon table and kitchenette and the skipper transmitting "Mayday". The crew is busy below deck packing drinking water, documents and food until a Swedish skipper turns the four of them away. Around 40 minutes after the first mayday, the French yacht sinks before their eyes.

In a conversation with Augustin Drion a few days after the yacht sank, he mentions that the skipper had the old rudder replaced with a new one before crossing the Atlantic. Was it possibly so heavily dimensioned that the destructive force of the four to seven tonne orcas was transferred to the hull via the rudder?

What we know about the orca attacks

What sounds like a detail from Frank Schätzing's novel has become reality. Since a yacht was first attacked off the Strait of Gibraltar in the summer of 2020, attacks on yacht rudders have been repeating themselves. Wolfgang Michalsky is a surveyor in Huelva, Spain, and has been analysing damaged yachts for forty years. He views the development with concern: "It's not just the number of orca attacks that is likely to be significantly higher than previously assumed. I expect around five hundred yachts to be damaged in two years."

According to my observations, the severity of the damage caused by the killer whales is also increasing."

"Officially, two yachts have sunk as a result of orca attacks. According to my research, however, the total number of yachts that have sunk is probably higher."

Currently, around three per cent of all crews that pass the Iberian Peninsula on long voyages report minor to serious damage due to encounters with orcas.

Analyses of the hundreds of vessels damaged by the attacks show that 80 per cent of them were conventional sailing yachts, the vast majority between eight and 15 metres long, although some were as long as 35 metres.

But it is not just sailing yachts that are affected: The remaining 20 per cent are fishing boats, multihulls, motor yachts and inflatable boats.

The number of orca attacks is growing rapidly

In 2020, three animals were identified as exhibiting the unusual behaviour towards yachts, and by autumn 2022, around 16. According to all research, however, the number is even higher.

Until now, they have all belonged to the Orca Iberica group, around 50 animals that live off the Strait of Gibraltar for most of the year - with the exception of a few weeks in winter.

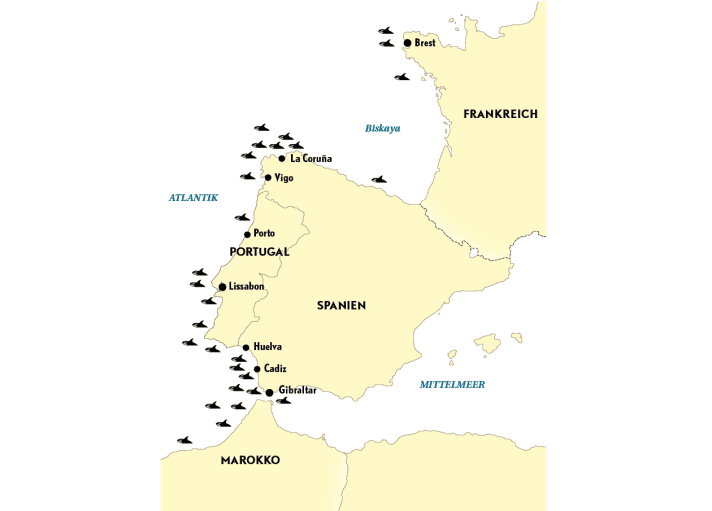

The attacks also spread from the original hotspot off the fishing harbour of Barbate to the entire western continental coast. The northernmost attacks were reported off Brittany, the southernmost on fishing boats and yachts off the Atlantic coast of Morocco.

However, the majority of cases occur in several hotspots off the Iberian Peninsula, such as Barbate or A Coruña in the north, and in 2022 also off the southern Portuguese port of Sines, the Tagus estuary and the Portuguese border region in the north. Orcas only very rarely stray into the Mediterranean.

Hotspots for attacks on sailing yachts

The orca attacks have a pattern

As different as the attacks are, the details from the above report and the stories of many of the skippers interviewed are very similar: the surprising suddenness of an attack, the intensity of which the skippers compare to a grounding. The number of animals involved is usually between one and four, almost always including a juvenile.

Orcas interact with pleasure boats in a variety of ways: forcibly stopping them, turning them up to 360 degrees with their heads, thrashing the hull with their tail flukes. However, the aim of all these actions is clearly to search for the most vulnerable part of the yacht: the rudder blade.

Why do orcas attack sailing yachts?

There are countless theories as to why killer whales choose the rudders of sailing yachts, and there are more every day. They range from revenge for the death of a baby orca injured by a sailor to aggression, increasing competition for food with fishermen in the Strait of Gibraltar, gambling and hunting, and even brain diseases as the reason why the animals no longer avoid proximity to boats as they did ten years ago, but actually seek them out.

In fact, the level of pollution of the oceans with the "dirty dozen", those twelve environmental toxins such as PCBs, which can be detected in water and soil even decades after they were banned due to their longevity, is alarmingly high - especially in the Mediterranean and particularly west of the Strait of Gibraltar. As orcas are predators without predators, non-degradable substances accumulate in the bodies of whales that live up to a hundred years. High mortality rates among newborns, reduced fertility and miscarriages have long been documented as a result of PCBs and other substances and are not only bringing the orca population off Gibraltar to the brink of extinction.

The most common theory is that the increasing human interaction, especially in the busy Strait of Gibraltar by freighters, fishermen, leisure boats and fast-moving ferries, has exceeded all limits and caused the Orca Iberica to fight back.

Orcas are amazingly intelligent

Orcas are very familiar with coastal life. After humans, they are the most widespread mammalian creature on the planet. Like humans, they are coastal dwellers. Conflicts are predetermined - with fishermen who hunt for tuna off Gibraltar like the killer whales and who often become the hunted themselves.

The sound of a running winch, which the fishermen use to haul a tuna from the depths on longlines, is the "time for dinner" signal for the orcas, as they pounce on the fish wriggling on the line. Often only a shredded carcass arrives at the surface instead of a sushi-grade tuna.

Anyone who takes a closer look at orcas knows that the animals know what they are doing. Orcas have a tremendous amount of brains."

Says biologist Fabian Ritter from WDC, the German branch of Whale & Dolphin Conservation. "Their brain is strikingly similar to that of humans. But it is twice as big as ours and weighs five kilograms, which is more than three times as much. Orcas have had this brain for several million years, whereas we have only been working with ours for 200,000 years. We are dealing with a very old intelligence. And we should always be amazed at what they can do."

In fact, people are amazed when those affected report the ingenuity of the orcas in their attacks. Thomas Kreuer from Düsseldorf took the encounter with killer whales, which destroyed his rudder mechanism within minutes off A Coruña, very calmly. But the hour he spent being towed by the Spanish sea rescue service was the worst of his life. Three orcas on one side and three on the other played ping-pong with the yacht, ramming into each other's boats from left to right.

Video summary of orca attacks

US sailor Brandon Sails also experienced horror minutes long after his rudder blade was destroyed by an orca attack: "The orcas were gone. Except for one. Its head was sticking out of the water a few metres from the boat, as if it was following every movement of the people on deck. At that moment, I realised the full extent of their intelligence. He was a guardian who was supposed to watch out and alert the others as soon as I started the engine and moved on."

If the orcas are approaching, you should flee in the opposite direction as quickly as possible"

Experiences like these have been documented many times. They show that there could also be astonishing and unexpected connections with the behaviour of killer whales. And some that leave us speechless. The Portuguese sailor Arthur Skipper, for example, an experienced dog trainer, is still convinced that he has found a way to communicate with the animals during their attacks and to calm them down.

How should you react to orca attacks?

In previous years, there was a period between mid-December and mid-February when the number of damages caused by orca attacks was close to zero. Based on his statistical analyses, John Burbeck from the British Cruising Association, for example, raised the question of whether the winter months might not be the best time to sail the Orca Alley, as British sailors have come to call the route around Western Europe due to the killer whale incidents.

But everything will be different in 2023. At the end of January, a Spanish sailing crew cast off their lines in the fishing harbour of Barbate to cross the Strait of Gibraltar and head for the marina in Tangier, Morocco, four hours away. At around 3 p.m., they are still an hour away from their destination when suddenly, 30 metres off the port side, an orca with a sharp hook heads for the stern of the yacht.

A crew member had the presence of mind to capture the scene on video. "There are two of them!" the viewer can see one of the crew members warning excitedly. It takes less than ten seconds before the animals are at the helm, as if there were no other target for them. One of the sailors reaches into the plastic bag in the stern and scatters sand into the yacht's wake. Everything happens very quickly. Then the video shakes and the recording stops.

He will later report that there were three orcas, two larger and one smaller. "We started throwing sand down. Our video stopped because two of us were throwing sand with both hands. First they disappeared, then they came back. We had about 20 kilograms of sand with us and you have to keep throwing.

I would say it works, but you need a lot of sand, much more than we had with us. As soon as the sand was gone, they immediately returned to the rudder. We then set off four firecrackers 30 seconds apart, but that didn't really work either. The orcas hit the rudder three times with momentum, but after what felt like two to three minutes they were gone."

Experiences of 40 skippers

Was it only a brief attack? Was the defence against the orca attack with sand successful? Was the crew simply lucky because the orcas had already fulfilled their "quota" of demolished oars that day? Among the 40 skippers interviewed in detail, there were only a few where active defence through noise, reversing or other measures was able to deter or scare off killer whales.

Resistance is as unreliable a means as its opposite. The recommendation of the Spanish and Portuguese authorities: "Stop the journey immediately, switch off the echo sounder and engine", only led to success for a few respondents.

Whale experts also disagree. Renaud de Stephanis, who has been researching marine mammals for two decades and tries to mediate between affected fishermen, sailors and whale conservationists, is currently experimenting on converted sailing yachts with funding from the Spanish authorities and researching sustainable methods to keep the animals away.

He recommends the exact opposite and never tires of emphasising: "Dumping sand doesn't help. If orcas approach, you should flee in the opposite direction as quickly as possible."

Contradictions such as this make it clear that we are a long way from being able to make reliable statements about causes and reliable defence measures.

One thing is certain: anyone planning a cruise from the German coasts to the Mediterranean should familiarise themselves with the phenomenon of orcas just as intensively as with the weather on the Atlantic coast. New apps such as Orcinus or reports on the website of the British Cruising Association help to keep track of the current location and the latest incidents.

Whatever causes these intelligent animals to attack the rudders of sailing yachts: What they do is also a message to us, not only as sailors but also in our everyday lives, to think about how we treat the oceans.

Or, as marine biologist and whale researcher Jörn Selling puts it: "I feel sorry for the sailors. Perhaps you are paying with your sailing boats for what others have done to the orcas. But perhaps you are the better ambassadors to bring about positive change."

The author Thomas Käsbohrer

After his professional life as a journalist, author, film-maker and publisher, the sailor, who lives with his wife on Lake Starnberg, spends several months a year travelling the coastal waters of Europe on board his "Levje". He has already written numerous books in the process. For his latest title "The enigma of the orcas" (millemari, 24.95 euros, also available as an e-book and audio book), Käsbohrer interviewed a large number of experts and 40 skippers about their encounters with killer whales and the question of why they attack yachts.