Reports about this presumably most extreme, innovative and fastest monohull ever to sail under the German flag are always snapshots. They only reflect a temporary state that may be outdated shortly afterwards - due to further developments or damage. The second leg of The Ocean Race made this clear once again.

Starting the race on new foils that had originally been built for a completely different ship, "Malizia - Seaexplorer" in the South Atlantic, around 3,000 nautical miles from Cape Town, suddenly presented her crew with a puzzle. Cracks in the shaft of the starboard wing mounted in the hull indicated that even the hastily installed replacement profiles might not be able to withstand the stresses of the swell. Will Harris, who had stood in as skipper for Boris Herrmann, who had injured his foot, spoke about the problem for the first time in a video from on board on 1 February. He seemed dejected and dismayed. The team, which had lost contact with the leaders in the calms, had actually wanted to finally put the pressure on in the south-east trade winds off the Brazilian coast.

"We have realised that we have a little damage to the starboard profile," said Harris, who has been part of the core "Malizia" crew for years. "So we have to be a lot more careful with it and hope it doesn't get any worse, because there's basically no way to repair it."

Even more serious: if the foil breaks, the Ocean Race would be over for the German team. This is because there is no longer a replacement that could be installed quickly. In an interview with YACHT just two days before the cracks in the aft edge became known, Boris Herrmann confirmed: "There is no alternative. These foils cannot be allowed to break." In the end, the foils held, "Malizia" was even in the lead after a race to catch up until shortly before the finish in Cape Town. There, the foils were reinforced again before the start of the third leg.

Many teething troubles with "Malizia"

It was not the first time that the Hamburg skipper's fans had to tremble and be strong. Even in the early stages of the Route du Rhum, Herrmann was plagued by a number of malfunctions: Firstly, the engine was a bitch, then a backstay blew out, whereupon the lashing of the Genoa 2 forestay came loose. Finally, the bolts on the upper foil bearing broke; the boat, which was actually optimised for heavy weather, came to a standstill just when it encountered its ideal conditions: a fresh, strongly gusting trade wind from astern with a swell of two to three metres. While Charlie Dalin, Thomas Ruyant and their pursuers logged 500 nautical miles, Herrmann sailed with his wings tucked in at slow speed, at only 15 knots, when the best were making more than 25 knots.

The transfer back from Guadeloupe to the start harbour of the Ocean Race was not without its problems either. When the technicians inspected the boat in Alicante, they found long cracks in the shaft of the foils with the naked eye. A subsequent ultrasound examination revealed even more extensive damage: cracks up to 20 millimetres deep in the full carbon laminate. The extended wings, which were around four metres wide and made from high-modulus carbon fibre by a robot using a state-of-the-art process, were therefore hazardous waste. Loss: around 600,000 euros.

These boats are very complex. They need a year or two to mature. Some things even the designers don't quite understand yet - like why the original foils are broken" (Boris Herrmann)

The fact that team director Holly Cova was able to find new foils at lightning speed proved to be a stroke of luck. The replacement pair with the crescent-shaped tips was actually intended for the Imoca of former Class 40 champion Phil Sharp, which is still under construction. His boat will not take to the water until early summer, which is why he could do without the wings.

They were designed by Sam Manuard, one of the hottest architects in the class at the moment. And as if by chance, they could be fitted into the hull structure of "Malizia - Seaexplorer" without any major modifications. Nevertheless, the open-heart surgery took several weeks and kept the composite specialists in the team busy non-stop over the entire festive period until the beginning of January.

Imocas are built around the foils

You have to imagine the foils as the chassis of a Formula 1 racing car, actually even more than that. Because the mast height and sail area are limited by the class rules, i.e. the "engine" is throttled, the hydrofoils are the most important component for the performance of the latest Imoca generation. Robert Stanjek, co-skipper of the French-German campaign "Guyot Environnement - Team Europe", says: "Boats today are basically built around the foils."

How early they lift the hull, how level and stable they make it slide over the water, how well they can parry wind shifts or gusts will ultimately decide who wins or loses. And of course: how reliably they work.

In this respect, the foil conversion of "Malizia" was a huge experiment. Would the new profiles, developed for a much lighter and more delicate boat, harmonise with the more voluminous hull? Would the performance parameters fit? How would the sailing characteristics change due to the fundamentally different wing shape?

Ten days before the start of the first leg of the Ocean Race, when the crew set sail for the trial run, there was a palpable sense of nervousness on board. The wind was offshore and only moderate at around twelve knots, but it should be enough to get the Imoca foiling. On a half-wind course, "Malizia - Seaexplorer" took off effortlessly, reaching speeds of 15 to 17 knots over long stretches and even 18 knots at the peak. During the second test in fresher conditions, she logged up to 28 knots. Boris Herrmann and his team even took victory in the In-Port Race, a kind of prelude a week before the official start of the Ocean Race.

The foils remain the problem area of "Malizia"

So all good? Foil conversion a success, boat in top form? As much as the start gave cause for hope, question marks remained. The new hydrofoils showed signs of wear on the shaft as early as the second test, which the team kept to themselves. To be on the safe side, the boat builders laminated two millimetres of carbon fibre between the upper and lower bearing in the foil box before the first start - as much as was possible so as not to impair the catching up and lowering of the profiles.

The new Imocas are so fast! One moment you can be ahead, the next behind. All it takes is a small mistake, a wrong decision when choosing a course" (Nico Lunven)

Even more worrying: so far there are only various theories, but no definite explanation for the breakage. The engineers at the VPLP design office, who designed the Imoca, are still looking for the cause; Avel, the manufacturer of the profiles, is also involved. The original foils were recently examined again using ultrasound. It could take "another two or three months before we understand what happened," says Boris Herrmann.

Only then can the team think about more durable, possibly even more efficient wings - provided the budget allows for another pair. This will be too late for the Ocean Race because the construction alone would take at least three to four months - assuming free capacity could be found, which is doubtful.

In the worst-case scenario, if the latest damage proves to be too serious, participation in the rest of the race could even be at stake. Foils, which have to withstand dynamic loads of more than 20 tonnes, cannot be repaired at will and can only be reinforced to a limited extent.

"Malizia" is made for the harsh Southern Ocean - but therefore also very heavy

End of the line in Cape Town? It is a scenario that cannot be completely ruled out - even if it would be extremely painful for the team and its hundreds of thousands of fans to quit the Ocean Race before the longest, toughest, the queen stage. Especially as "Malizia" was designed precisely for this - for the rough Southern Ocean.

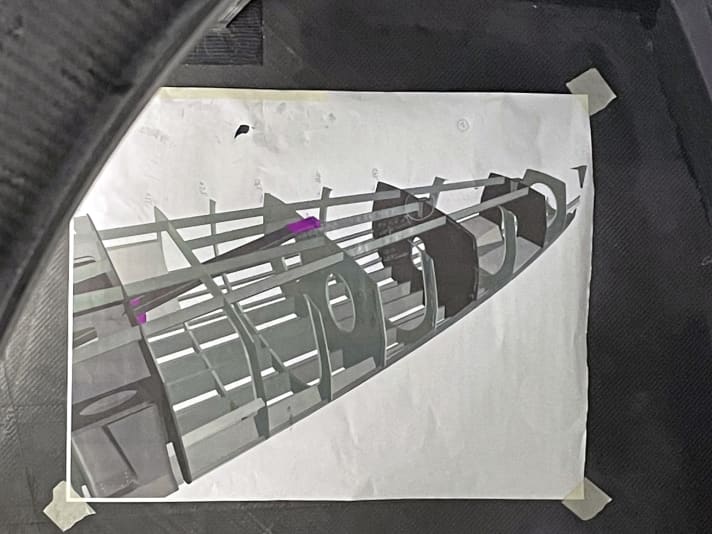

That's why she has so much freeboard, hence the most extreme bow section, but in return she has more keel jump: all measures to ensure that she doesn't drill into the back of lakes ahead if she is travelling faster than them. Hence the extremely robust construction with closely spaced bulkheads, stringers and frame frames, which make the hull practically indestructible. "Our strong, fat boat," says co-skipper and navigator Nicolas Lunven, a description that is somehow meant affectionately, but also sounds ambivalent. Because it's an open secret: "Malizia" is one of the heaviest of the new Imocas. Engineers both inside and outside the team suspect that the foil problems may also be related to this.

The boat carries the lightest possible ballast bomb on her forged keel fin. To ensure the capsize safety required and tested by the class, VPLP designed the aft crew cabin with windows reminiscent of a pilot boat. The superstructure, wider at the top than at deck level, provides additional buoyancy and supports the turning momentum if the boat should capsize. This increases the living space on board and at the same time helps to save weight in the keel - a win-win innovation.

There is a whole litany of such innovations on "Malizia - Seaexplorer". The cockpit, which is located directly behind the wing mast, offers full standing height and an ergonomically positioned winch platform that enables efficient trimming - a rarity compared to the rather cave-like sheds in which the crews work on "11th Hour Racing" or "Holcim - PRB", for example, always bent over, sometimes even crouching on their knees, with winches mounted just above the cockpit floor to keep the centre of gravity low.

Details that make a big difference

The German boat also sets standards in terms of all-round visibility. The pulpit above the cockpit is so generously pierced by windows that nobody has to go on deck to check the sail position or take a bearing of the sea ahead. In addition, cameras, infrared sensors and a broadband radar provide an additional overview in rough weather with a lot of overhanging water. The helmsman, who usually only steers using the autopilot, sits in an elevated position on fold-out composite seats in a kind of window dome that offers optimum visibility. In contrast, the cockpits of competitor boats look like dungeon cells.

On deck, behind the mast, every sensibly usable surface is covered with special solar cells from Solbian, which offer increased slip resistance. In this respect too, "Malizia" claims an exceptional position. Together with the two lightweight hydrogenerators on the transom, she is largely energy self-sufficient, meaning that when the sun is shining, she generates all the electricity consumed by the many electronic systems on board from renewable sources. The Lombardini diesel only serves as a backup and as propulsion during harbour manoeuvres and in emergencies.

The companionways on both sides are designed to be as seaworthy as the wide running decks and the carbon fibre handles on the aft cabin superstructure. They can be covered with a short, tunnel-like tarpaulin so that no water can find its way into the cockpit in rough seas, where it would quickly drain away through palm-sized bilge openings anyway.

"Malizia" can be steered like a dinghy

Standing or sitting in the companionway is a good place to keep watch when the weather is favourable. The boat is also steered from here during stage starts or in-port races. A V-shaped carbon fibre tiller, mounted in the middle and connected to the quadrant via long Dyneema strops, allows the helmsman to steer the 20-metre high sea racer like a dinghy - extremely directly, with only small impulses and without great effort.

We sail 99 per cent under autopilot" (Boris Herrmann)

Sitting on the same axis, there is also a V-shaped tiller below the cockpit ceiling, here with longer ends to reach up to the helmsman's seats. For tricky manoeuvres or to check the balance of the boat, it is therefore possible to switch to manual steering from below deck at any time. However, this is the absolute exception. "We sail under autopilot 99 per cent of the time," says Boris Herrmann. Steering a foiling Imoca yourself would be extremely challenging and in the vast majority of cases slower, because human sensors can no longer keep up with the latest technology.

No one can explain how sophisticated the control system is better than Axelle Pillain, who designed and installed it and wrote parts of the software herself. "In principle, there are two levels of self-steering," says the PhD mathematician, who sailed the Mini-Transat in 2019 and also acts as a stand-in for crew member Rosalin Kuiper.

"We have a Hercules H5000 system from B&G, which forms the basis, so to speak, and would also work on its own." Above it, however, is another, much more sophisticated control unit called Exocet, manufactured and programmed by Pixel sur Mer, a highly specialised high-tech company in Lorient. "It calculates the true wind angle in real time and allows the crew to set various parameters at the touch of a button, which are also taken into account and optimised by the course computer," says Axelle Pillain: "Boat speed, position and the apparent wind angle." The system then "plays" with the course within these set values, and if desired with almost brute force: faster, more sensitive and, if necessary, harder than even the most experienced helmsmen.

All modern Imocas are equipped with this technology or with the similarly functioning counterpart from Madintec, an IT company also based in Lorient, which specialises in steering foiling Imocas, Ultim trimarans and other high-end yachts. Their autopilot is called MadBrain, a nerve centre for all encoders that costs almost 20,000 euros in the highest configuration level and transmits steering commands to the rudder with an accuracy of a tenth of a degree.

"Malizia" is packed with sensors

"Malizia - Seaexplorer" not only represents the state of the art in this respect. It is also the boat with probably the most comprehensive collection of load sensors. The hull, foils, rudders and mast alone contain 150 fibreglass strain gauges that provide information on pressure and deformation. There are also load pins in the rigging, which can be used to monitor the tension on halyards, stays and shrouds.

Technically, their data could even be implemented as control variables in Exocet or MadBrain. If certain load limits are exceeded, the autopilot could, for example, drop out or start to glide. However, integration does not yet go that far on any Imoca. Nevertheless, the sensors are extremely important in order to give the crew any indication of when things are getting critical via alarms.

Especially in the initial phase last year, "Malizia" was constantly beeping as soon as she was foiling. In the meantime, the threshold values have been raised to such an extent that warning signals only sound rarely. When this happens, however, the crew's first glance is at the "load page" on one of the iPads permanently installed in the cockpit to assess whether or not action is required. Will Harris explains the importance of the complex measurement technology: "To be honest, an Imoca of the latest generation feels like it's going to explode at any moment in the wind. You're actually constantly thinking that you need to slow down." That's why the load values are indispensable. "You simply have to trust these figures. The boat hums, bangs and crashes deafeningly into the waves. But as long as none of these alarms go off, you can trust that everything is OK on board."

An Imoca feels like it's about to explode in the wind" (Will Harris)

It is a kind of ocean sport in which intuition and seamanship are still important, but are increasingly being supplemented, and in some cases replaced, by algorithms and measurement technology. "You now have to be a computer nerd to move these boats to 100 per cent of their potential," says Will Harris.

Surprising findings remain despite data volumes

Data not only plays a key role on board. On land too, when analysing performance and evaluating the boat on an ongoing basis, the sensors provide important and potentially decisive information. Specialists in the team scrutinise all the measured values that are uploaded via satellite radio. The architects at VPLP are also trying to understand the design better and better. In addition, data analysts from KND in Valencia are searching for further potential in the sea of megabytes.

But not everything can be modelled mathematically. "Certain findings are surprising," says Boris Herrmann - "such as the fact that we are faster on certain courses with the new foils." That's also the beauty: "that not everything can be calculated in advance by the computer, that the feel for the boat still plays a role," says the 41-year-old, who is one of the most eager innovators in the Imoca class, but has remained an instinctive sailor and sailor.

The new Imocas have become much more demanding with the increase in foils and, as a result, speed. This was already evident in Alicante in light to moderate conditions. Because it takes time to change the angle of attack of the hydrofoils using the hydraulics, the boats tend to take off with the bow in gusts - the skippers refer to this as "wheelies" in the style of motorbike racing. It looks and feels spectacular on board. However, such a take-off is not efficient, because after the usually rough landing, speed has to be built up again.

The howling of keel and foils is gruelling in the long run

But even if the boats get onto the foil cleanly and race almost horizontally across the water, simply keeping on course is not enough. Keel tilt, autopilot and mainsheet tension have to be constantly readjusted to maximise speed. The helmsman becomes a video game junkie, pressing a button every few seconds. The crew also rarely have a break because the main has to be tightened again as soon as it is hoisted.

Ideally, this leads to rapid acceleration, which can throw you off balance even in flat seas. A current Imoca jumps from 12 to 18 knots upwind at an angle of incidence of 65 degrees in barely more than the blink of an eye, and it needs just 3 to 4 Beaufort to do so. A good 22 knots are possible under these conditions, and even 25 knots in gusts, accompanied by the howling of the wing and keel fin, which lends the breathtaking increase in speed its own note, even if it sounds gruelling in the long run.

However, if you are careless, the sound and speed will drop just as quickly as soon as you miss a turn or a push. Only then does it become understandable why all skippers with ambitions of winning rely so heavily on foils, why the boats become more and more extreme. If you drop from 20 to 12 knots while the competition is still travelling in flying mode, or if you come out of the water later than them, you inevitably feel like you're standing still.

And yet there is the downside, which is perhaps not quite so noticeable in the Ocean Race sailed by crews of four, but all the more so in solo regattas: "The more powerful the boats become, the more fine-tuning is required," says Boris Herrmann. "The old Imocas were much more suitable for single-handed sailing. At some point, you simply had the feeling that they were sailing close to their performance potential and then you could let them run."

Foil swap a "happy accident" for Boris Herrmann

With the new foils, if they hold, "Malizia" has even won in this respect. They are "more tolerant", says the man from Hamburg, and require less meticulous adjustment. Upwind and on half-wind courses, they are even said to be slightly superior to the original foils because they not only generate lift, but also lift upwind. Boris Herrmann therefore refers to the breakage as a "happy accident". He only expects a certain loss of speed in light winds and generally on deep courses.

But even that is just a snapshot. How efficient "Malizia - Seaexplorer" really is can probably only be said with certainty after the Ocean Race, perhaps even after the Transat Jacques Vabre in November, when the foil problems have been completely resolved. "These boats are very complex. They need a year or two to mature," says Boris Herrmann.

At the launch last July, he said: "Now we have to wait and see how the construction proves itself. Maybe I've pushed the architects too far into a corner."

Technical data "Malizia - Seaexplorer"

- Designer: VPLP

- Torso length: 18,28 m

- Total length:20,12 m

- Waterline length: approx. 14.90 m

- Width: approx. 5.60 m

- Depth: 4,50 m

- Mast height above waterline: 29,00 m

- Weight: approx. 9.0 tonnes

- Sail area on the wind:approx. 280 m²

- Motor (Lombardini LDW 1003):30 HP