Some owners, especially those with a small crew, generally like to avoid reefing: if more than 4 Beaufort is forecast, they only motor or don't sail at all. Charter companies have also been observing this trend for years: Above wind force 4, the diesel is started, and below 3 as well. Convenience is on the rise in many places.

Apart from the fact that this unnecessarily restricts you in your trip planning and you miss out on the very uplifting feeling of sailing a yacht that is perfectly adjusted to more wind effectively and really fast, the safety aspect also plays a role. A thunderstorm or rain squall can catch anyone out, and despite modern technology, the weather forecast is often wrong, for example because downdraughts, cape or jet effects are added to the gradient wind.

It is an enormous gain in safety if the skipper and crew are clear about what procedures to expect when reefing is necessary. Which sails are reefed first and how much. How to balance the boat perfectly. This reduces the amount of time crew members have to spend on the dancing foredeck or at the mast in rough seas. A necessary step in the development of a good skipper and his crew.

On the water, however, you often see other things: yachts pushing along with killing sails and far too much lay, extremely wrinkled furled mainsails and headsails, wildly flapping leeches, sun shots.

The different types of reefing:

When is the right time to reef?

A first question for many crews is when a reef is necessary. An old truism says: if you think about it, it's usually already due. This is certainly a bit of an exaggeration, but it illustrates well the reluctance that some people harbour against reefing.

Reefing on the upwind course

The fact is, a yacht gives clear signals to the helmsman on the upwind course and up to the half-wind course if it is carrying too much surface area. Rudder pressure and position increase. If the boat starts to luff uncontrollably, the reefing point has usually already been exceeded. With the enormously wide sterns of modern cruising yachts, a central rudder is then levered out, the current breaks away and the inevitable result is a sun shot. This is one of several reasons why double rudder blades are becoming increasingly popular. The smaller but angled blades are in an optimal vertical position when they are in a more favourable position, they are less inclined and less air is sucked in.

Reefing the furling mainsail

Many modern boats are no longer very effective beyond 20 degrees due to the shape of the hull. They run less height, the drift increases and the material is subjected to high loads. And on top of that, it is uncomfortable to sail with an unnecessarily large amount of leech and also a safety issue, especially for older crews or those with small children.

Reefing a mainsail with mast slides

However, it does not have to be reefed immediately with increasing pressure and position. The reefing time can also be postponed a little: The first step is to flatten the sail profiles. More backstay tension flattens the mainsail and at the same time reduces the sag of the genoa. The lower luff extrusion flattens the lower part of the mainsail. The mainsail traveller can be moved slightly to leeward. If you use the trim control to the full, you can sometimes successfully delay the reef until the next destination.

Easy: Reefing the genoa downwind

Many people make it unnecessarily difficult for themselves with the simplest manoeuvre. It is important to choose the right course before starting to reef. If the yacht is in the wind when reefing, as is still taught in many textbooks, the cloth flaps wildly and can endanger the person on the foredeck. In addition, the flapping of the sail puts so much pressure on the fittings that furling is hardly possible. In fact, the furling line is often torn when the genoa is furled, in which case the only solution is to retrieve the sail, which is much more time-consuming.

Therefore, the genoa should be dropped to a downwind course for reefing or recovery, if the sailing conditions allow. The genoa is then covered by the mainsail and has hardly any pressure. In addition, the forestay loses tension, which relieves the load on the fittings and makes it easier to turn.

As a general rule, if you can no longer pull by hand, you should not attempt to do so using a winch. If the force applied by hand is too high, this indicates faulty fittings or other faults. The entire operating chain of the genoa should then be checked. However, you will not notice this with an electric winch and run the risk of tearing something with its force.

Headsails with staysails should also be changed or recovered before the wind if possible.

Tips for trimming the sails:

Reefing with aft wind

It is more difficult to judge when to reef in aft winds. Most yachts can handle more sail area than upwind on these courses. A rule of thumb is to reef at the wind force at which you would also reef on an upwind course. Another indicator is the speed: if this does not increase despite the increasing wind, the yacht has reached its hull speed and is no longer going any faster. Too much sail area is therefore useless.

However, too much sail area can usually be used on courses with a stern wind. Most yachts are forgiving of this. However, you should be sure that it doesn't freshen up even more. Here, too, it is better to reef too early than too late. This is important because reefing itself can otherwise be dangerous. Conventional mainsails in particular cannot usually be reefed before the wind; they have to be luffed. However, only then can you really feel how strong the wind is actually blowing, and this can be much stronger than expected. Then the main will beat wildly and the handling will become more strenuous. It is therefore advisable to seek the protection of cover, such as a cliff, for this manoeuvre if the area allows.

Reef as a precaution

If it is already clear before casting off that a reef will be unavoidable, it is advisable for small crews in particular to consider calmly tying in a reef in the harbour before setting sail. It is much easier to reef outside than to be battered at sea by the first gusts after setting the sheet, even before the crew has acclimatised to the wind and swell.

In which order do you reef?

If all this no longer helps, the question arises as to whether the mainsail or the headsail should be reefed first or both together, as many sailors have probably learnt to do. This depends on the wind, the type of boat and the cloths used. To decide which should be reefed first, the sailor needs to know the boat a little: Is it a yacht where most of the power comes via the mainsail or via the headsail? In modern rigs with their smaller furling headsails, around 100 per cent, and higher, leaner mainsails, the latter is often reduced first. If the headsail does not have thickening foam strips on the luff, it is often better if even the second reefing stage only takes place with the main.

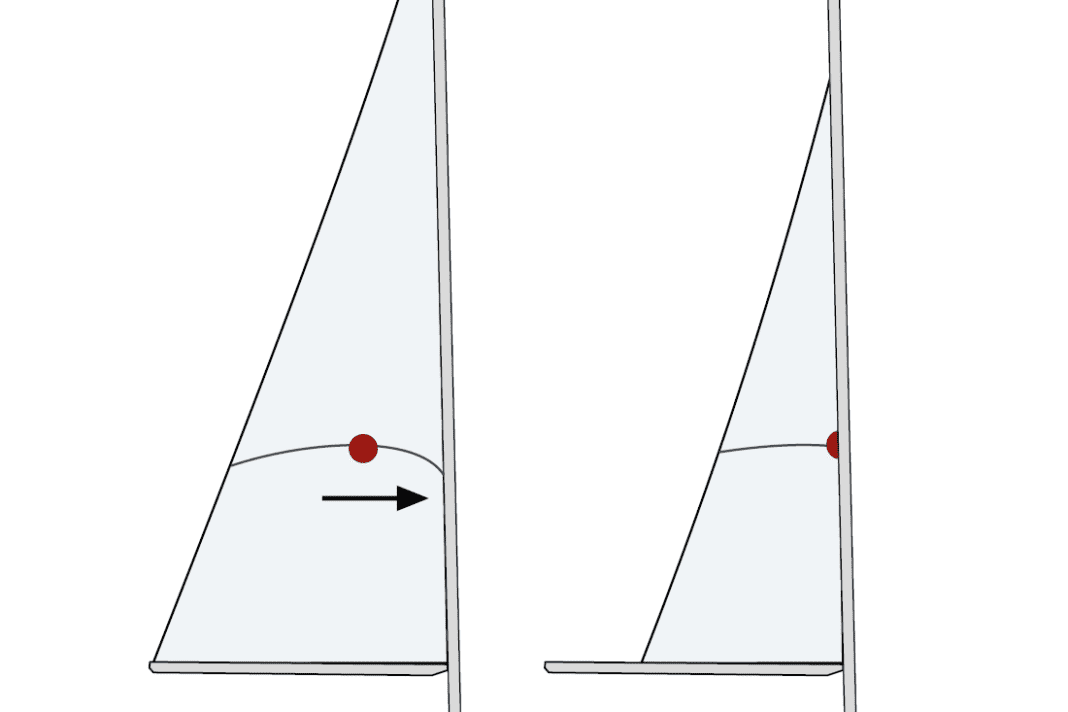

Pay attention to the sail profiles

This is especially true if the boat has a main with sliders. Then the sail shape is maintained and reefing does not have any serious disadvantages for the profile. This is precisely the problem when furling the genoa: the roll of cloth on the stay creates a poor inflow and the profile of the sail is no longer correct. In addition, the cloth is subjected to higher loads as the pull goes directly into it and no longer just onto the reinforcements provided for this purpose on the clew and tack.

On deep courses downwind, the order "first the main, then the headsail" makes more sense anyway, as a reduced headsail behind the main is often worse than the other way round.

The situation is different for many older boats. Some older yachts have huge, widely overlapping headsails. These are "genoa boats", so to speak, and there were designs with up to 140, 150 per cent sail area of the genoa. On such boats - the old Albin Ballad is a good example of this - the first step is to reduce the foresail area. Ideally, of course, this is done by using a smaller sail that is also on board. But many owners don't have this option because they don't want to change sails on the foresail. Accordingly, the genoa is gradually furled on such boats. Yachts with foresails above the 125 per cent limit are often in this category.

Occasionally you also see crews who take the main off completely and only sail with a headsail, at least when they don't have to cross. This is perfectly possible, but it puts one-sided strain on the rig and the masthead may be bent forwards. To counteract this, the backstay must be tightened - if this is possible. If the spreaders are heavily swept, this works in a similar way, provided there is enough rig tension in the basic trim.

Article on the subject of rig trim:

Owners and charter crews should follow these guidelines. How a boat sails when reefed often needs to be tried out first, especially if the wind is so strong that the main and headsail both have to be reduced beyond the first reef.

Prepare the reefing correctly

Whether the manoeuvre actually works smoothly is above all a question of preparation. What exactly does the skipper have in mind, what sequence of events is important? What course does he set, how rough is the weather, what safety measures are necessary on the forecastle? The tasks must be assigned to individual crew members and they must know what is important for their part of the manoeuvre. For example, it would also be conceivable for the helmsman to announce particularly high waves for the crew on the forecastle and try to manoeuvre around them if possible. Possible risks or problems should also be pointed out, for example if the crew is using e-winches, which can easily have the power to tear the sail if the manoeuvre goes wrong.

Prepared in this way, the first strong wind day can come - and even be fun.