This article is part of a sailing special. The contents:

What percentage of a cruising yacht's lifespan is spent sailing? Even if winter is excluded, the figure is probably in the low single digits. Even on summer holidays, a yacht is lived on more than it is sailed. Consequently, many boats are optimised with this in mind: they offer a lot of living comfort. The sail wardrobe consists of two furling sails, that's it.

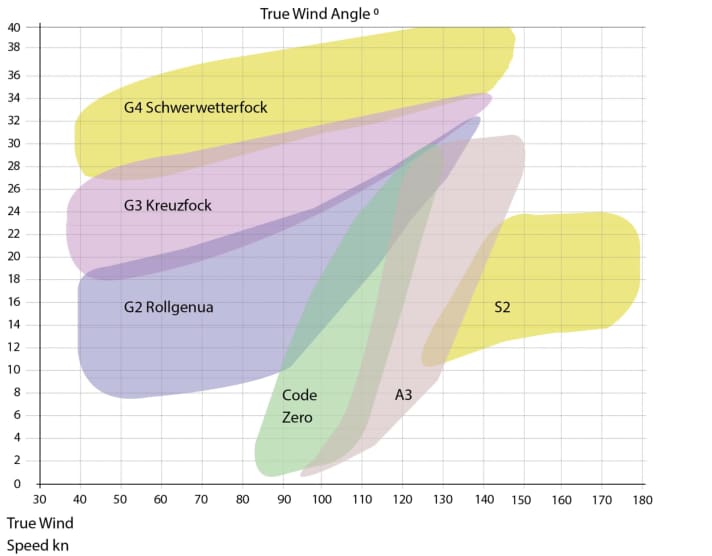

At the other extreme are regatta yachts that have five different genoas in the sail load alone and several more gennakers or spinnakers, plus staysails and other special sails. The right cloth for every wind and every course. Then it's easy to get ten sails and more, after all there are also code zeros and heavy weather sails. Here again, the question is: do so many expensive sails fit into the budget, and does the crew really want to keep lugging bags of sails onto the foredeck and constantly changing the sails?

The middle way between a material battle and an undersupply of sailing gear is advisable

This is because boats with only two sails usually don't perform in light winds. The reason is simple: problems in too much wind are much more daunting than the idea of starting the engine in less than ten knots of wind. This is why many furling sails tend to be undersized. An unreefed sail has the best stability. If the sails are ideal for light winds, i.e. wind speeds between five and eleven knots, you will often have to reef them and therefore usually have to accept a less than ideal stance.

This is because the profile always shifts when furling, regardless of whether the genoa or furling mainsail is used. In most cases - of course it also depends on which leech is furled - the sail then becomes too bulbous, which is ultimately undesirable in strong winds.

In addition, the unfavourable profile also has a detrimental effect on pressure distribution: more pressure in the leech causes the sail to age more quickly. The profile distorts, and the sail then also performs worse when unreefed. Smaller sail areas, which only need to be reefed later and therefore usually less frequently, are therefore a simple solution to increase the service life of the cloth. The disadvantage is less sailing fun and more engine hours in light winds.

A technical solution is offered by laminates with low-stretch fibres and special thickenings in the luff, which improve the stability of the reefed sail. This maintains the sail profile for longer. However, laminate sails also cost considerably more, and it is always better to have a cloth that is suitable for the wind strength and angle.

The decisive factor is the yacht's utilisation profile. So the first question is: Which sails do I need?

If you only sail your daysailer on sunny days in a light wind area, you may be well advised to use a large spinnaker, but you don't need a heavy weather jib. If you are not afraid of a long cross from southern Sweden to Kiel in 20 knots of wind, you will benefit from a suitable headsail. If the yacht is only used for short trips to the anchorage, two furling sails may suffice. A few miles can then also be managed with reefed, less than ideal sails.

A code zero and several gennakers can be a great addition to the existing sailcloth selection and provide more sailing fun on deeper courses. However, if you realise that you don't want to change sails on the foredeck and are happy with a furling genoa that is unfurled or unfurled at slightly lower speeds, they are still the wrong choice.

The choice of sails is very large. The easiest place to start is behind the mast, with the mainsail. Apart from the cloth and cut, the choice is limited to the number of reef rows and equipment details. Of course, it can also be more or less exposed. However, the rig type is usually the limiting factor here. A squarehead only works with masts without a backstay.

Bertil Balser from North Sails recommends two reefs, which then take away a little more sailcloth. "You usually tie in the first reef and then go straight into the second reef shortly afterwards. With 15 per cent less cloth in the first reef and 25 per cent in the second reef, the range of use increases," says the expert. He advises against a third row, as the fittings for the reefing line are then usually missing and have to be retrofitted at great expense. There is no need for this except on long-distance yachts that are travelling far from a safe harbour. Here, too, the decisive question for everyone is: Can I even go out in 30 knots of wind? If not, there is no need to have extra sailing gear for this eventuality. Short, sudden strong wind events such as a 40-knot shower can also be weathered with a small corner of the furled genoa. If you are worried about your sails, simply furl them completely.

The right headsail

Things get exciting with the headsails, where the choice is immense. Even with genoas that are sailed on a stay or furling system, four different sails or even more are conceivable. Starting with the Genoa 1, the foresail with 140 to 155 per cent overlap, up to the G4 with 85 to 90 per cent as a heavy weather jib. In addition to the utilisation profile, the type of boat and the fittings must also be taken into account when making a decision. For rigs with outboard shrouds and wide spreaders, a wide overlapping Genoa 1 may not be suitable, whereas a flat gennaker or a slightly lower cut Code Zero may work.

This does not quite give you the height of a Genoa 1. However, widely overlapping headsails are usually a hindrance on a cross anyway, as the long sheet paths require more work. In this case, a headsail with only a small overlap is generally preferable. For example, a genoa 3 with 110 per cent as a cross jib. While top-rigged boats with huge headsails used to be standard, most yachts are now equipped with a 9/10 rig and the headsails are smaller.

A self-tacking jib or cross jib can be practical, but the hoisting point must also fit. If the rails do not extend far enough forwards, this would mean that the clew would have to be positioned very far above the deck in the case of a non-overlapping headsail. This would not only result in a loss of performance, but would also be very impractical. This is because the outhaul would be inaccessible when furled.

The multifunctional turbo Code Zero

Code Zeros close the gap where the genoa is no longer as effective but the course is still too sharp for the gennaker, i.e. between 100 and 120 degrees true wind. However, this does not mean that they only work in this range. They are usually sailed on a furling system with a special anti-torsion cable, which makes setting and recovery easier. Nevertheless, Balser warns against treating them like a genoa. When motoring against 20 knots of wind, the furled Code Zero should not be left standing, it is not designed for that. There is too great a risk that it will partially unroll and be destroyed. These sails therefore require foredeck work and stowage space. This is because the anti-torsion cable together with the sail twine cannot be rolled up very small.

In addition to handling, the fittings are also important. In order to be able to sail a code sail on more acute courses, a lot of tension must be applied to the luff, as it must not sag far. This requires a 2:1 ratio halyard and low-stretch cloth.

But even with this type of sail, different profiles are possible. Bertil Balser recommends discussing exactly which course and wind range it should be suitable for with the sailmaker beforehand. As an all-rounder for cruisers, he recommends a Code Zero with a 65 per cent centre width.

There is no perfect sail selection for cruising sailors, but there is an approximation

There is also a large selection of gennakers. Here, however, the fundamental question usually arises: gennaker or spinnaker? Sure, they are two different types of sail, but the spinnaker is unbeatable on a long downwind run. Above 20 knots of wind, however, an unfurled furling genoa can also do the job of an S4, i.e. a small strong-wind spinnaker. However, the gennaker is often preferred anyway, as it is easier to handle. An A2, i.e. a deep-cut large gennaker, can do many things that a spinnaker can do, but it cannot manage the last 20 degrees to the downwind course. An A3 can be ridden higher, between 110 and 150 degrees. This means it can do a lot of things that a Code Zero can do, and if there is also a spinnaker on board, the flatter gennaker is unnecessary.

Sailchart: the application areas of different headsails

A good option is to look at the existing sail wardrobe to see on which courses and wind forces there are gaps (see sail chart above). For example, if a cross jib is missing on the wind at 15 to 22 knots or a spinnaker is already on board, but there is a gap between half and full wind that a code zero or flat gennaker could close. If a genoa 1 is on board, a code zero may not be necessary at all. In the end, sailors decide for themselves in which conditions and courses their sails work well. Just because the sailmaker specifies a genoa 2 between 40 and 130 degrees in eight to 24 knots of wind doesn't mean that it can't also work perfectly when unfurled at 170 degrees and 25 knots. The recommendation is therefore to try out your own sail wardrobe in different conditions and to test good combinations of different headsails and reefing levels in the main. If a new sail is then to be made, explain to the sailmaker exactly what it is to be used for. Then even small additions will have a big effect.

Parasailor, trysail & Co.: special cases

Special room wind sails for long distances in the trade wind are not part of the normal sailing wardrobe. There are double genoas that can be furled and reefed together, but can be unfurled in both directions like two sails. The parasailor is a type of spinnaker, but without a boom and very stable thanks to a wing, without much trimming. It can also be a good option for cruising sailors for long distances, but is more expensive than a spinnaker.

Special storm sails consisting of a small jib and trysail are mandatory for offshore races, but not absolutely necessary on cruising yachts. Normally you can make it to the next harbour with a heavily reefed genoa or under engine power. Very few people sail in storms. Heavy weather cannot always be avoided on blue water yachts, so storm sailing makes a lot of sense. There are many options: the best, but most expensive, is a storm jib on a separate stay. However, there are also cover sails that can be pulled over the furled genoa. Ideally, the trysail has its own track.

This article is part of a sailing special. The contents:

Michael Rinck

Redakteur Test & Technik