This article is part of a sailing special. The contents:

Companies such as Dimension-Polyant, Bainbridge and Contender have various technical tricks at their disposal for the production of classic woven canvas. The most important is the arrangement of the yarns in the fabric. All sailcloths are produced in the so-called plain weave, which means that the warp and weft yarns cross over each other evenly and alternately.

If the warp threads running in the longitudinal direction of the fabric are identical to the transverse weft threads, the result is an almost uniform fabric that is almost equally resilient in the longitudinal and transverse directions. This is almost because, due to the design, the warp threads do not lie straight, but run alternately above and below the weft thread. If the fabric is subjected to a load, it stretches slightly more in the warp direction. If the material thickness in the warp or weft is now changed, the structure of the entire fabric changes. The more material is added in each direction, the more stretch-resistant it becomes.

A high jib with a short lower leech is given more strength parallel to the leech with a so-called weft-orientated cloth, while a headsail with a long lower leech is better produced with a warp-orientated cloth. Sails between these extremes are sewn from "balanced" material. These areas of use can be found in the names of all manufacturers' products: Bainbridge and Dimension-Polyant call them "Strong Warp" or "Strong Fill", Contender refers to the low- or high-aspect area of use in the product name, while balanced cloths from Contender and Polyant bear the abbreviation AP ("all purpose"), Bainbridge calls it "Balanced".

More on the subject of sails:

Now the cloth manufacturers can do much more than just vary the thickness of the yarns. What is almost invisible to the sailor is the quality of the polyester used and the weave density of the cloth. One thing is clear: hardly any sails of standard original equipment quality are made from branded sailcloth. Poor yarn quality and imprecise weaving are subsequently concealed with a comprehensive but less durable final treatment of the cloth. This makes it difficult for the layman to distinguish it from a high-quality material when it is new.

Various methods can lead to a good canvas

Basically, the tighter a sailcloth is woven, the better it is, so the yarns per centimetre of cloth width count. However, it is almost impossible to obtain these material specifications and, due to the very atypical units of measurement, only something for insiders. Only Bainbridge and Contender provide information on this in their product sheets: For example, yarns with 300 denier strength (1 denier = 1 gram per 9000 metres) are used in the warp direction for the Strong Fill with a fabric weight of 329 grams per square metre, while yarns with 850 denier are used in the weft direction. Contender uses a combination of 200 denier in the warp and 600 denier in the weft for the comparably heavy High-Aspect (322 g/m2). This means that the latter fabric is finer because more thinner yarns are used for a comparable basis weight.

However, this comparison also shows that the technical details of competing products do not necessarily have to be similar, but that playing with different yarns allows for numerous solutions.

One development, for example, is to virtually reverse the weaving process between warp and weft. Instead of the warp thread winding around the transverse weft, Bainbridge, Dimension-Polyant (Pro Radial) and North Sails have now succeeded in weaving a cloth with a straight warp thread. This means that the material is particularly stretch-resistant in the longitudinal direction and is suitable for radially cut sails, for example.

Hybrid fabrics: Pentex, Dyneema and others

Polyester sails no longer make up the lion's share of production in today's aftermarket, even if their mechanical durability is still superior to that of laminate sails.

If it is already possible to weave yarns of different strengths together on the loom, the obvious next step is to combine simple polyester cloth with high-strength fibres to reinforce it. These blended fabrics, also known as hybrid fabrics, are still too heavy for regatta sailors despite their high-tech content, but they open up new possibilities for cruising sailors. Dimension-Polyant was a pioneer in this respect when it launched "Hydranet" on the market. This was the first time that Dyneema had been successfully woven into sailcloth. The robust material is popular with blue water sailors.

For example, the "Square" fabric, also from Dimension-Polyant, is much easier to work with. Here, ripstop-like yarns made of Pentex are woven at regular intervals, a material that is particularly popular with standardised classes because it conforms to the rules. This allows the weight per unit area to be reduced by a few per cent. The mix of fibres with different levels of stretch in one fabric is still controversial. Such hybrids are still niche products that are only processed by many sailmakers on demand.

The right finish for the sails

But weaving alone is not everything. It takes a coating to turn a soft fabric into suitable sailcloth. This finishing of the cloth is often referred to in brochures as a "finish" and involves two steps. The first is the so-called calendering. The fabric is pressed between two heated rollers; this heat and pressure treatment hardens the structure. During "resinising", the subsequent coating process, the gaps in the fabric are filled with a plastic cocktail that is mixed differently depending on the requirements. In the most extreme case, such a hard finish can harden the fabric to such an extent that it holds its shape very well, but destroys the underlying fibres when it is broken. White breakage is an extreme form of premature sail ageing.

Sailmakers therefore recommend medium to soft end treatments for use as a touring sail, so that the sail can be folded and reefed without any problems, but is also not damaged too quickly during chilling.

However, this durability is bought at the price of poorer tread fidelity. Fabric after-treatment is also a Trojan horse, because with a lot of resin, even the worst fabric becomes a respectable product at first glance - and in the first season - hardly distinguishable from premium quality by the layman.

What surface weight is required?

The sailmaking scene is international, and so the various suppliers use several units of measurement to represent the surface weight of sailcloth. The most common is the simple indication in grams per square metre, but it is also measured in ounces. This is not a classic unit, but the sailmaker's ounce (smoz). It refers to an area of 28.5 to 36 inches in length. The conversion factor in grams per square metre is therefore 42.83.

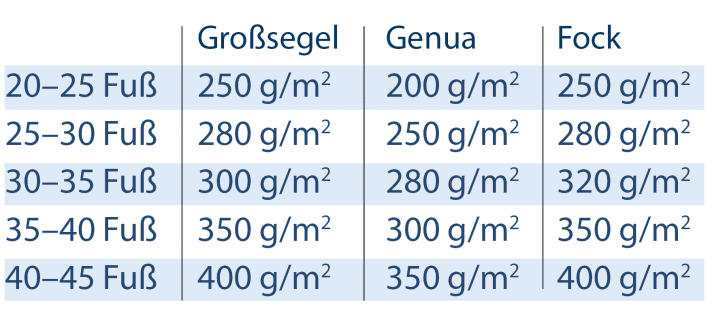

But how heavy should the sailcloth be in order to be suitable for your boat? This is a question that cannot be answered without further information, as the weight of the boat, area of use, type of sail and durability requirements all play a part in the decision. Some of the data is usually available to the sailmaker - if you have been a customer for a long time, you rarely have to say much about your usage behaviour. In general, higher cloth weight can compensate for poorer weave and yarn quality to a certain extent, but the resulting additional costs should be invested in fundamentally better quality.