It is a dark, merciless night as the coal-black "Guyot" hammers through a gale-force North Atlantic storm. A small but brutal depression off the US coast is testing Team Guyot on course for Newport with winds of up to 60 knots. The influence of the Gulf Stream makes for a nasty cross sea. Nevertheless, there is cautious optimism on board. Skipper Ben Dutreux, navigator Sébastien Simon, co-skipper Robert Stanjek and Annie Lush, the most experienced person on board on her third circumnavigation, know that they only have to hold out for another hour or two. Then the low will be over.

Read also:

Co-skipper Robert Stanjek goes on watch with this hope after a demanding few hours. On the way to his bunk, he takes one last look at the wind display: 56 knots. With three reefs and no headsail, the eight-year-old "Guyot" has made good time so far at a reduced speed of 15 or 16 knots. Stanjek hands over the mainsheet and thus also the helmsman's responsibility to Seb Simon and falls into a restless doze. The hammering of the boat in the raging sea shakes him again and again. Then he nods off again. Until a scream makes him jump in shock: "Broken mast!" Accompanied by desperate cries of "Oh, no, no, no, oh, no" from Ben Dutreux, he hurries off.

Robert, how do you remember the mast-breaking moment in the stormy night on stage four?

Robert Stanjek:I had tried to sleep. You always wake up in between when it's really rattling. Then you're gone again. I didn't notice the mast breaking. I woke up to the call "Dismasted". There was only an hour to go and we would have been out of the storm ...

How did you react?

With good crisis management. Ben and I got dressed. I went straight to the repair bag and brought the big tools on deck. We took a quick look at the situation. The rig was completely broken. 25 metres of mast were floating in the water, a four and a half metre stump was lying on deck. Everything was still connected by the mainsail, the tangled headsails, backstay and all the lines. We had to make a quick decision. The mast had to move away from the boat in a six metre wave. If it hits the side of the boat at an obtuse angle, everything is in danger.

Did you agree on the procedure?

It was the first time that I had seen the French somewhat paralysed. The shock was due to the situation. They tried to think about what they could do to save themselves. I was able to make it clear to Ben that we had to cut immediately.

Was there collateral damage?

Not a big one. The mast damaged our starboard foil at the tear-off edge. Both rudder blades took a knock. Two bulkheads also broke in the storm. We're not sure whether this is directly related to the mast breaking or whether it happened beforehand. Our compass can read three-dimensional forces that have entered the hull. When the mast broke, we had 9g.The ship weighs almost nine tonnes. An incredible force was at work. It's possible that these two bulkheads broke immediately beforehand and the mast came down as a result. But you can't hear it in a storm like that.

The disappointment and frustration in the team was almost greater than the damage ...

At that moment, I thought it was completely impossible that we could come back into the race a second time after the delamination on the Cape Horn leg, the turnaround, the repair, the re-entry and now this gigantic knockout blow. I thought that was it for the Ocean Race.

You continued sailing under jury rig and engine. When did new hope emerge?

We looked at options in all directions. Then I got a call from Marc Pickel, who I know well from the Olympic star boat days and as an experienced boat builder from Kiel. Marc said: "Come to Kiel, we'll repair your boat at the Knierim shipyard and I'll help you organise it." He was very moved by our broken mast. He believed in it and convinced me.

A bold, but also very ambitious plan.

Yes, the boat had to be transported from Hamburg, the mast provided by 11th Hour Racing from France to Kiel. Marc put together an outstanding, experienced team of boat builders. They were like an old band that got together again and gave a top concert for six days in a crazy atmosphere. They were led by Killian Bushe, who had already built four winning Ocean Race yachts. Knierim Yachtbau and so many people supported us in Kiel. Our French team members were very impressed that something like this also works in Germany. It was a tough but also inspiring two weeks with at least ten U-turns: We can do it, we can't do it, we can do it ...

What were the problems?

One day it was a transport licence for a low-loader from Hamburg to Kiel. The next, it was the money again. We had to start without knowing whether we could manage it financially, otherwise we wouldn't have made it to Aarhus in time. Then the shipyard said that it wouldn't be possible to repair the damage to the bulkheads in time. But there were always other opinions on top of that. An incredible sense of solidarity developed among the Ocean Race teams and the race organisers. A wave arose that made us take responsibility for seeing it through. Jens' motto was: "We have to make the impossible possible once again."

What did you have to repair in the almost 1,000 hours of work at the end of the rescue mission?

The tasks were varied and extremely demanding due to the short time available: the two bulkheads - the Achilles heel at the beginning of the timeline. Also the foil and the two rudder blades. Plus two other minor damages in the ship, including the keel box. The mast blank from France had to be refitted with customised standing and running rigging as well as the electronics.

The Ocean Race's decision to support you with collateral, among other things, only came late in the evening of 1 June ...

Everything was knitted with a hot needle. Redemption came after a marathon of negotiations with Jens and Ben on a Thursday evening - a week before the Aarhus start. It meant: new private deposits and additional financing with the bank with strong Ocean Race support.

Your second comeback was completed one day before the start of stage six ...

We received a very touching welcome in Aarhus. We then fought and fought and fought on stage six. The fly-by in Kiel was emotional, wonderful, the reward for many ordeals. At the end of the leg, we finished in fifth place again. But then we had a little run, not only achieving the best 24-hour distance on stage six, but also winning the speed races in The Hague and the harbour race - a nice hat-trick.

Did the positive trend persuade Ben to take the wheel at the start of the final stage?

I had already handed over the wheel once at the Inshore race in Brazil. That didn't go so well. After that, we had a more intense discussion, which was necessary so that we could focus on our strengths in the crew again. But the helmsman has a high media profile, which I think Ben - strengthened by his victory in the harbour race - also wanted for the start of the stage. That tickled his ego. Fair enough. I offered to do the tactics, but he wanted Seb to do it. Annie and I were supposed to work out the manoeuvres in the boat. Which is why I can't say much about the crash moment, because I'd just taken off the mainsheet for the tack and put on the jib sheet. We were already in the next manoeuvre.

In a kind of "blackout", your team overlooked 11th Hour Racing's "Malama" and impaled her with the bowsprit. By luck, nobody was injured ...

I wished for a hole in the ground where I could disappear. Seen from a distance, the whole thing had two levels: firstly, the disaster that we took 11th Hour out of the final. Secondly, the fact that we cut off twelve days of excitement from the Ocean Race. If we had experienced a sailing thriller right up to the last minute, it would certainly have been important for the marketing of the follow-up edition. We were very grateful and relieved in Genoa that the jury's decision led to a well-deserved victory for 11th Hour Racing. The other teams were very friendly towards us there. That shows the enormous social side of the Ocean Race. Nobody is left behind.

How did you deal with the crash and the blame within the team?

We didn't talk about it enough. Ben did say that he would take full responsibility, but ultimately there was no real discussion.

As a team, you often gave the impression of an alliance of convenience. It seemed as if the French and the German-international group of Offshore Team Germany never quite got together ...

This had less to do with the French and Germans and more to do with solo sailors and team sailors. The French solo sailors had the all-important technical Imoca expertise that we didn't have. But they also had difficulties articulating their thoughts, delegating or sharing things. They quickly found themselves travelling alone and then also in French. Especially when things got tricky. That wasn't always good and also happened in other areas of the team. It was difficult to find a reasonable compromise between the different philosophies.

Do you have any other examples?

The downline for the foil broke on stage four. We were in a good position during a fast phase of the race. We should have reflected: Will we reach our shore manager? What do we need to repair? Should we continue sailing with a 20 per cent speed reduction until a more favourable repair window appears? Instead, I couldn't see as quickly as the foil boxes were open. The French tried to pull in a new line, but unthreaded the broken one the wrong way round. This caused the oversized eye splice to get stuck in the constrictor clamp. As a result, we lost the safety line for the new sheet and were unable to feed it into the system for the time being. This was not well thought out and at the wrong time. In the end, we got back on course with a huge loss of miles.

You, Annie and, on other stages, Phillip Kasüske didn't have a chance to assert yourselves more strongly?

Ben owns the boat. He is the skipper. The second man with technical responsibility was Sébastien Simon with his Imoca background. Decisions like this are made quickly, quickly, quickly. Once the child had fallen into the well, they realised that they had reacted too hastily. The action was symbolic of many a decision. They are simply solo sailors. Nevertheless, we were always a good team.

You finished sixth in the Star boat at the 2012 Olympics and then switched to offshore racing. You toiled for almost eight years to realise your dream of the Ocean Race premiere. Has it become a nightmare?

I wouldn't put it like that. But there are certainly painful gaps in this circumnavigation. So it is "unfinished business". But there are also wonderful moments and positive emotions. I saw my picture of this on stage four, when we hadn't even reached the halfway point: huge black mountains of clouds with a silver rim - silver linings. The term fits well with our campaign. We are still ocean racers. We made it to the starting line in difficult global times. This competition is multi-layered. It doesn't stop the moment you break something. It shifts to logistics, financing or technical areas in order to come back again. We have written a different story than planned. The way we resolved the situations is also an achievement.

You couldn't solve the delamination of your hull floor, which forced you to turn back on the historically longest royal stage. It was the stage you wanted the most ...

Yes, and it had started so well. Before the start, race director Phil Lawrence had called us together for a briefing and said: "We've already lost two sailors on this leg. I want to see you all in Itajaí." If you looked at the media beforehand, it was like a competition to see who could find the scariest headline. That also increased our respect. But we were well prepared.

Nevertheless, you had to give up three days after the start ...

We had started the race strongly and were in second place behind Holcim - PRB. The weather forecast looked like the boats in front would even be able to extend their lead. We then ended up in the first, very strong low-pressure area. We were travelling very fast in waves six or seven metres high. The forces acting on such a half-foiling, half-flying boat were insane. I have rarely experienced such movements in a boat.

Around 4 a.m. on 1 March you had a change of watch ...

I got out of the bunk, took ages to get dressed because I was flying through the ship. I came out, Annie went down. They had previously gone from reef three to reef two. She gave me a look that told me to push, that we were going back to reef three. I discussed this with Ben, but reefing always means losing time. Annie stuck her head out of the companionway and said: "Guys, the floorboard downwind is delaminated." She was referring to a not very reinforced area in the bottom of the hull, about three by one metre in size. It's a Kevlar honeycomb sandwich. If these materials, each of which is very flexible in itself, separate, then you no longer have any structure. It lifted six to eight centimetres and made a very crumbling noise. It was pretty scary in the storm.

How did you decide to turn back?

We called our Shore team. These are two people who are available 24/7 and never get on an aeroplane together. The decision came half an hour later: turn back! It was a shocking setback.

As a team, you had the smallest budget, the least experience and a boat that was eight years older than the competition - how would you weigh these factors in relation to the many setbacks?

There is something to be said for the fact that we had too little experience as a team in some places when you compare us with a crew like that of 11th Hour. I think it's also true in comparison to Holcim - PRB. Boris also has an incredibly experienced army of people. They have all done a great job with their new boats, which actually take a year or more to develop. Despite different expectations, there were few failures. Sometimes it was very tight, like with Malizia. If they had broken their foils a week later, they wouldn't have been ready in time for the race. Or their crack in the mast due to the halyard being torn out - they were also on the verge of turning round. Sometimes you just have that tailwind and the crew to sort out a situation like that, and sometimes it doesn't quite work out (laughs). There's not so much in between for things to go well or you have to turn round and make a plan B.

What good memories will you still take with you?

We took a picture with 50 or 60 German people in Alicante before the start. I think it's great that we can now bring so much new Ocean Race experience to Germany through them and many others. It should also be noted that there was the biggest media response of all the countries in Germany. Jens, our team and certainly our dramas contributed to this. And of course Boris and Team Malizia. I thought it was great that he invited me to sail on "Malizia" in Genoa.

As Offshore Team Germany, do you have your sights set on a new Ocean Race attempt to close the gaps?

Let's take a deep breath. It would certainly make sense to utilise all the experience, what we have learned and what we have experienced in both good and bad times in a second campaign. If we make a plan, it has to be finalised before Christmas. The Ocean Race Europe 2025 offers a low entry threshold. We could try something there. But before that, there is reflection, rest and the ORC World Championship in Germany.

This might also interest you:

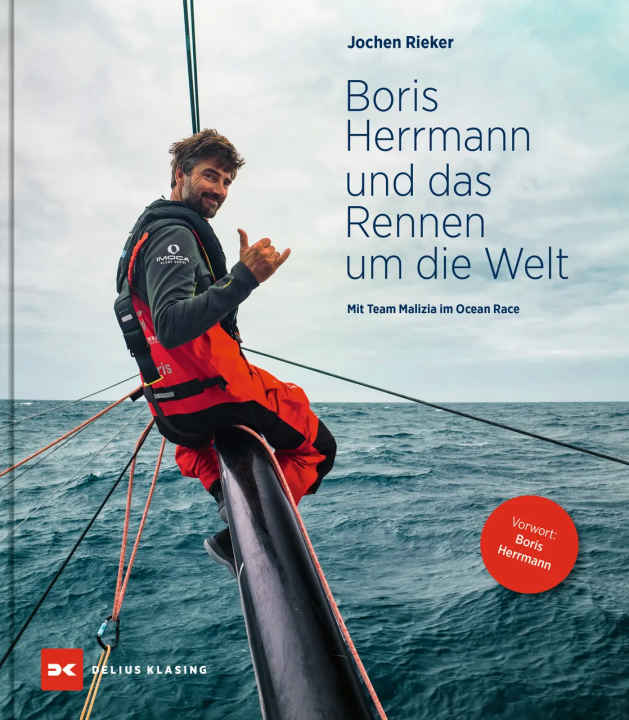

The book about the race

"Boris Herrmann and the race around the world"

With this illustrated text book, you will be up close and personal: at the christening of the new high-tech yacht "Malizia Seaexplorer", at the first tests of the racing projectile, at the growing together of the team, at all the highs and lows of the prestigious sailing race around the world! In addition to spectacular sailing pictures from the race and directly from on board, the official Ocean Race book also contains a personal foreword by Boris Herrmann.