In this article:

Legerwall- What does that actually mean?

A lee shore describes a dangerous situation in which a ship gets closer and closer to a lee shore due to onshore winds, ground swells or strong currents and runs the risk of becoming stranded if it is not able to cross free or gain distance with the help of the engine. When anchoring, it is also possible for a ship to run aground after a wind shift and increasing wind forces. For example, if the distance to all sides of a bay has not been sufficiently calculated or the anchor breaks free.

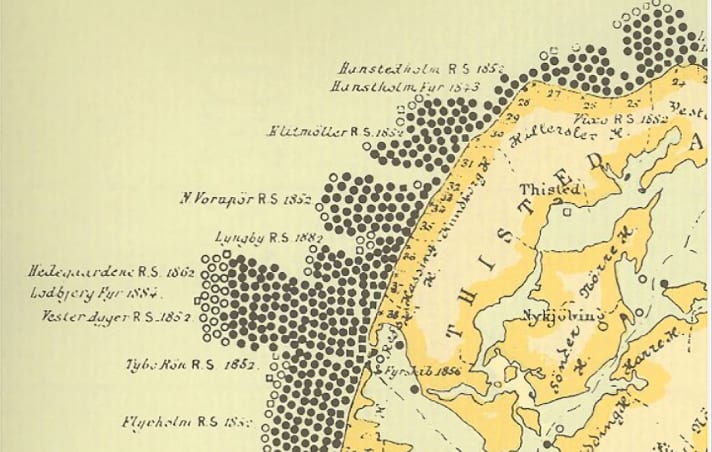

For the historic tall ships with their powerful superstructures and typical square sails, the leeward bulwark posed a particularly high risk, as they offered a lot of windage and did not have good cross characteristics. In addition, the navigational possibilities for precise positioning were much more limited in the past than they are today. As a result, the German or Danish west coast, for example, with its offshore islands, sandbanks and reefs, became a deadly trap for countless ships.

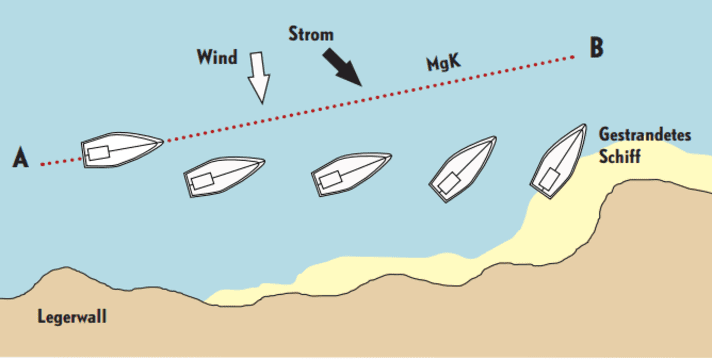

Nowadays, the dangers lurk elsewhere. For example, if the helmsman of a yacht only ever orientates himself to the next buoy without taking a look aft. Depending on the offset caused by wind and current, the ship then gradually drifts further and further out of the fairway - which may go unnoticed for a long time. In such a case, we speak of the infamous "dog curve", as shown in the diagram below.

This is how quickly dangerous situations can arise

September 2021: A single-handed skipper rushes towards the southern approach buoy of Marstal with set sheets in 22 knots of wind from the southwest. The wind is too good not to savour it for as long as possible. Shortly before the buoy, the main is lowered and the engine started. With the genoa and engine running, we luffed up and set off on a half-wind course. "At the second pair of buoys, I started to pull in the furling genoa," recalls the sailor. "That's when the mishap happened: the reefing line got stuck, and the next thing I knew, the sheet, whose figure-eight knot had come undone, was rushing through. It not only ended up in the water, but also in the propeller!" His ship immediately drifted towards the shallows to leeward, unable to manoeuvre.

The skipper reacts quickly and throws the stern anchor, which he always has to hand. This enables him to save his ship from a serious grounding. Only the front part of the keel has already dug into the silt. The rudder, which is orientated towards the anchor, is still floating freely in the water. Time to take a breather - and to radio the volunteers from the Danish Sea Rescue Service (DSRS).

In the end, this dicey situation turns out well. However, this is not always the case. Recently, there have been more and more cases of yachts running aground and getting stuck or even stranded, sometimes with catastrophic results for the ship and crew.

Causes of leeward wall situations: inexperienced skippers and overconfidence

Ulf Kaspera, Director of the Federal Bureau of Maritime Casualty Investigation (BSU), confirms that the majority of reported accidents involving recreational craft can be attributed to lee shore. "Especially during the coronavirus boom and the associated increase in inexperienced skippers, there was a significant increase in groundings and strandings. Many skippers had either not been on the water for a long time, or they were overconfident after buying their first boat or with a freshly printed recreational boating licence."

In addition to overconfidence, lack of preparation, unfamiliarity with the area and technical failure are the most common causes. In 2021, the BSU was notified of a total of 65 cases in German waters involving recreational boats under engine and sail in connection with groundings, 20 of which were charter yachts.

This year, too, there were numerous strandings on the leeward coasts of Germany and Denmark. One Curious case made headlines in mid-September when a Russian stranded on the North Sea coast of Jutland was taken care of by German tourists and eventually asked for asylum in Denmark. His original plan was to sail to North America.

The list of DGzRS rescue missions includes many more such accidents: On 14 September, a single-handed sailor's journey ended on the west side of Juist. The man was rescued ashore by the surf. On 24 September, the four-man crew of a British gaff-rigged ketch was rescued from danger off Norderney after their ship ran aground. A trimaran had already run aground in the mudflats near Mellumplate on the Outer Weser on 6 August, whereupon a woman who required medical assistance had to be rescued.

Small problems become a chain reaction

But even experienced crews can be affected if, for example, an initially minor technical mishap in strong winds triggers an unfortunate chain reaction that can no longer be controlled. In this year's Golden Globe Race, the crew member who had been at the helm for 30 hours and completely exhausted Guy deBoer on its passage through Fuerteventura, the ship fatally decides to pass upwind of the coast. Overtired, he apparently falls asleep - only to run onto a rock a short time later. He was almost thrown overboard on impact. The 66-year-old, who was ultimately rescued unharmed, was self-critical afterwards: "It was a bad decision not to pass Fuerteventura downwind. I had to pay dearly for that!"

Harbour entrances can also turn into veritable cauldrons in onshore winds due to high, breaking waves and strong cross currents. In 2017, for example, a disastrous yacht accident occurred off Rimini in Italy when a Bavaria 50 was thrown onto the jetty. Four crew members were washed off board and drowned, and the keel, rigging and rudder of the ship broke. A fierce bora with winds of over 40 knots had taken the experienced crew by surprise, so they decided to head for the harbour with radio support from shore. However, a combination of engine failure and a foresail that could not be unfurled led to disaster.

The German training yacht "Meri Tuuli", an X-Yachts 442, was also doomed by a harbour approach in 2013. The crew had tried to reach Figueira da Foz in Portugal in onshore winds. However, a high wave from astern caused the boat to list and the mast broke. During the subsequent rescue operation, a police officer and a crew member who had already been rescued lost their lives after a rib that had been rushed to help also foundered. The yacht and rib were later washed up on the beach. The images from back then still send a shiver down your spine today.

Harbour entrances can become an obstacle

However, the danger does not only lurk in distant waters such as the Adriatic or Atlantic. There are also harbour entrances in the Baltic Sea that become an obstacle that should not be underestimated when there are a lot of waves. In Kolberg in Poland, for example, where the harbour entrance is located in a river estuary, huge shock absorbers are fitted to the long jetty to prevent the worst from happening. Basically, however, every harbour entrance or entry can turn out to be a challenging manoeuvre in unfavourable weather conditions. You should therefore always be well prepared.

Courageous manoeuvres, an optimal entry angle that takes wind, waves and current into account, as well as good timing are the most important prerequisites for reaching a safe berth in the harbour without damage. The entire crew must also be instructed and secured with life jackets and life lines.

Some harbours are closed when the weather conditions are appropriate or are expressly recommended to be approached with extreme caution, if at all. If in doubt, it is safer to weather out on the open sea and wait for better conditions. Or to take a longer route in order to head for a more accessible harbour.

In August this year, a storm front proved that anchoring or mooring at a supposedly safe mooring buoy can end in a nightmare when the winds from the sea increase. This had travelled from the west across Corsica to northern Italy and cleared entire bays. Numerous yachts ended up between the rocks and on the beaches.

Does the insurance cover Legerwall accidents?

You can hardly protect yourself against such an unannounced severe hurricane, it is force majeure. However, if onshore, stronger winds are forecast and the skipper reacts inadequately, then there is not only the risk of losing the boat, but possibly also trouble with the insurance company afterwards. Charter skippers risk losing their deposit and may even face recourse from the charter company's hull insurance. This can quickly add up to enormous sums.

A good skipper's liability insurance, which also covers gross negligence, and of course careful seamanship, will protect you from this. After all, when in doubt, it's also about your own well-being and that of the crew. In addition to assessing the weather forecast, this includes finding a safe anchorage, checking the anchor gear and organising anchor watches.

When sailing off a lee shore, on the other hand, it is important to keep as far away from the coast as possible. To do this, you need to find out about the area beforehand and take care both at the chart table when navigating and at the helm when steering. Otherwise, it is easy to overlook shallows or coastal currents - which can be dangerous.

Even more caution is required if there are no alternative routes due to narrow channels. This is the case, for example, in island-rich areas such as the Danish South Sea. Or on the North Sea in the area of the tidal flats between the Wadden Islands. Tidal currents are an additional complicating factor there.

The anchor is the last resort

It is therefore advisable to keep the engine running when things are likely to get tight so that you can react as flexibly as possible at all times. And be careful with all lines: if one gets into the water and gets caught in the propeller, you will quickly suffer the same fate as the skipper in the case described above. The last resort is often a quickly dropped anchor, which hopefully holds the boat before it runs aground.

Professional skipper Leon Schulz advises: "A dragged anchor, whether at the bow or stern, which can be dropped as quickly as possible if necessary, is part of good seamanship. It can literally be used as an emergency brake before a serious grounding or even stranding occurs." He therefore also recommends never skimping on an anchor. Schulz: "In my opinion, light plough anchors are not much good and have no place on board a seaworthy yacht!" Before such an emergency anchoring manoeuvre is carried out, you should of course try to get out of the dangerous situation. The sails should therefore always be clear for quick hoisting if they have previously been recovered under engine power, for example.

If the boat does run aground, this does not necessarily mean the end. Depending on the nature of the seabed or in reasonably moderate wind conditions, there is often still a good chance of freeing yourself under your own steam. Then it's time to release the sheets to take the pressure off the sails and try to get back into open water with the engine running in reverse. The crew may be able to help by shifting onto the fouled boom to heel the boat. This manoeuvre can also be supported by an anchor cast to windward, the line of which is retrieved with a winch.

In strong winds, however, these measures are superfluous and the only option is to radio the sea rescuers. You shouldn't wait too long to do this either.

How to avoid or free yourself from Legerwall

- Lee instead of windward: If possible, always choose the coast facing away from the wind. If something goes wrong, there is more time to adjust to a new situation.

- Plan B:If there is no other option than to sail close to windward on a coast, for example in narrow shallow water passages, always have a plan B or even plan C in mind - and familiarise the crew with it.

- Allow for currents:Pass a windward shore with concentration and foresight - the slightest mishap can lead to disaster in a flash. If currents go unnoticed, on the other hand, this can have serious consequences.

- Anchor clear to drop: A modern and sufficiently heavy anchor should be on board and clear for dropping. This buys time in an emergency.

- Weight and long chain:If only a light anchor is available, tie additional weights to the anchor or chain. A long anchor chain also adds weight and flattens the angle of pull.

- Chain and leash:Always attach the anchor chain to the boat with a line so that it can be cut quickly and easily if necessary. The line also serves as a shock absorber and protects the boat.

- Small sails, greater safety: It is easier to cross with a reefed main and small headsail. Therefore, reduce the sail area in good time when the wind picks up.

- Keep sails clear for setting:Don't just rely on the engine. If it fails unexpectedly, it must be possible to set sail at lightning speed.

- Sparks: It is better to call the sea rescuers for help sooner rather than later. The safest way to do this is by radio. Especially as other ships in the vicinity can also listen in and help.

Book tip

50 tips for cruising

- from Leon Schulz

- Delius Klasing Verlag, 336 p., 24,90 Euro

- Order here >>