High on the wind in the Småland fairway. The wind picks up, the anemometer soon shows 20 to 25 knots on average, and in the gusts the wind even rises to 30 knots. The mainsail is already in its second and final reef. Actually, the jib still has to come down and the storm jib put on.

The first thought: turn round! But then we realise that this is not a good solution. The weather conditions are not expected to improve over the next few days and we are due to arrive home in Maasholm in two days' time.

Yesterday I came from Skåre in Sweden and entered the supposedly sheltered Småland fairway south of Møn to spend the night in the island harbour of Bogø opposite Stubbekøbing. And now this! The plan was actually to moor in Omø harbour this evening before nightfall. But this plan is now a long way off.

Single-handed sailors are on their own

These situations would certainly be more relaxed with a crew. Not only because there would be more helping hands available, but also because you could simply exchange ideas and discuss things.

But that's just the way it is, and after all, I chose it that way. I watch my wind pilot, my second "man", for a while, then cast off the jib halyard and crawl towards the bow.

One hand for me, the other for the manoeuvre. Unless the wind is specifically forecast to drop, I always prepare the next smaller sail in the harbour. In my case, this means that the storm jib is already attached and tied to the sea railing. The jib now only needs to be recovered, the halyard and sheets shorn onto the storm jib, the stays of the working jib cut off and the sheet secured to the railing.

Now crawl back, set the storm jib, tighten the sheet, and yes, it feels much better.

Three hours of wind and sea shake my boat and me upwind. The course is changed from Omø to Bisserup. This brings with it the prospect of a mooring in the light. And suddenly, in the land cover, east of Bisserup, things are going well again. The sea has calmed down, the wind has dropped to 20 knots and I can even reach my originally planned destination of Omø again. Later, I reef out again and switch to the jib.

Suddenly everything is marvellous again. I reach my destination in daylight, as planned in the morning. And looking back, the three hours of strong wind aren't too bad either.

Single-handed sailing is not always voluntary

It's a good feeling to be able to cope with situations like this without outside help. Of course, it's easier with a well-coordinated crew. And of course, shared suffering is only half the suffering on board. On the other hand, you first have to find those with whom you can master difficult situations better. In most cases, the circle of potential co-sailors with whom you would like to be in the same boat when the going gets tough is limited to a small group. And not all of them have time when you need them.

While sailing practice is important before day trips, single-handed sailors are also concerned with mental issues before long distances

As a family crew, we try to consistently spend strong wind and bad weather days in a sheltered harbour. This is made possible by the strategy of sailing longer distances alone. This is because the longer we sail in one go, the greater the risk of encountering bad weather en route.

Once the destination has been reached, for example the sheltered waters of the Swedish archipelago, the rest of the family joins them.

We have done this on many trips, including an Atlantic crossing, and everyone is very happy with the concept. Over the years, I have familiarised myself with the subject and have now become a real fan of single-handed sailing.

Single-handed sailing is something special

It is a kind of feeling of freedom to be able to assess and control the ship, the elements and ultimately myself. Being on my own and still being able to overcome all problems and enjoy beautiful moments in solitude always fills me with a deep sense of satisfaction.

Admittedly, single-handed sailing is a broad term. Of course, there is a difference between sailing from harbour to harbour on the Baltic Sea and spending days and weeks in complete solitude across an ocean.

While the skills required for daysailing alone focus on techniques that you need to have on hand, the long passages also emphasise mental issues. It makes a difference to acquire tricks and tactics for harbour manoeuvres and heavy weather days or to solve problems in advance that arise from being alone for days and weeks coupled with a lack of sleep.

While it has always been my ambition as a skipper to have the boat under control even in tough conditions, I couldn't answer the question of how I would cope with the constant loneliness before my Atlantic crossing.

Mental problems with single-handed sailing

And who can do that - our lives are characterised by daily encounters with other people. Under normal circumstances, hardly anyone finds themselves in the situation of not seeing or perhaps even speaking to anyone for days or even weeks. How are you supposed to know what that feels like?

I was lucky. I was able to enjoy most of my journey. However, it should not be concealed that there were also phases of deep depression. The question of why I was actually doing this to myself overshadowed the trip several times. Heavy weather, darkness, lack of sleep - you have to be prepared to get through it all, if only for the feeling of having made it.

In hindsight, however, it was worth it for me. Sailing alone across the Atlantic will always remain in my memory as a very special experience that I wouldn't want to have missed.

Preparation is important

Anyone setting off alone on such a long voyage should already be practised and not have to worry about the actual navigation of the ship. Mooring in strong winds, reefing, changing sails in tough conditions, repairing and improvising - you not only have to be happy to do all this, you should also be able to do it in unfavourable conditions.

However, what will inevitably be part of the cruise preparation is an intensive examination of the respective ship, its technical equipment and possible improvements for operation by the single-handed crew.

The ability of the skipper is more important for single-handed operations than the particular design suitability of his vessel

It is often said that the single-handed capability of a sailing yacht is characterised by special design features. But this is not necessarily true. When sailing without a crew, the skipper himself and what he is comfortable with is much more relevant than the boat.

Is there an ideal single-handed yacht?

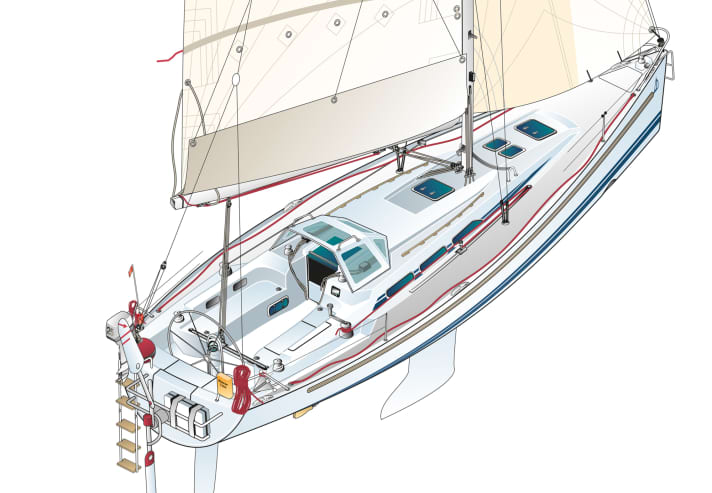

The deflection of all halyards, outhauls and reefing lines into the cockpit, which is often desired by sailors, has the disadvantage that their many deflections generate a high level of friction, in addition to the churning that they quickly cause there. Anyone who has set or reefed the sails from the cockpit and mast on comparably sized ships knows how much more difficult it often is in the deflected version.

The simpler, the better, is my personal credo, which applies not only to the line guide, but also to the electrics and electronics. Everything that is built in will inevitably break at some point. On the high seas alone, you're happy when equipment is manageable and easy to repair or replace.

Of course, opinions differ widely on this point. Some people still sail around the world with a sextant and towed log. However, the majority of sailors today are travelling on boats with a collection of instruments that NASA would have been envious of just a few decades ago.

Even though I don't belong to either of these two camps, my heart beats more for the sextant faction. But these are all questions that everyone can answer for themselves according to their own preferences. There are no clear pros and cons.

Is an autopilot mandatory?

The situation is different when it comes to the autopilot. This is firmly at the top of my equipment list for single-handed sailors. If you want to be particularly well-equipped, you are even recommended to ensure redundancy. On my boat, this is provided by a wind steering system and a tiller pilot, which is designed for much larger boats. This means that my boat continues to be steered reliably when I'm below deck or working on the foredeck.

Depending on the sailing area, and especially if you are also travelling at night, you should have an AIS device installed, or at least a receiver. Especially when it comes to sleep, you will be glad if you can read the "closest point of approach" or the "time to closest point of approach" on the device.

Informed in this way, the decision may then be made to let one or two freighters or fishermen pass for safety's sake before going to the berth. The acoustic alarms available as a result should not be underestimated.

Single-handed sailors lack hands in the harbour

However, single-handed sailors face special challenges not only when underway, but also and above all during harbour manoeuvres. As mundane as it may sound, centre cleats and two large ball fenders are essential for me. There is hardly a mooring manoeuvre where they don't make my life much easier.

For all my mooring manoeuvres in boxes, the aft lines are led through the centre cleats to the back of the winches. This allows me to steam into the lines and calmly sail to the jetty with centimetre precision. Then the lines are set, and while the engine remains engaged forwards, I go forwards and set the forward lines.

If I want or have to go alongside, one large ball fender comes quite far forward, the other quite far aft. A line with a maximum of two metres of slack is attached to the centre cleat on the corresponding side.

The jetty or quay wall is then approached in such a way that, after stopping, there is an opportunity to moor ashore at the height of the centre cleat. A very short slip over the centre cleat is then made there.

The boat is now only hanging on a very short line at its widest point, but only swings up to one of the ball fenders and is fixed for the time being. Now it can be moored in peace.

For me, making ready to enter the harbour with sail hoisting, attaching lines and fenders only takes place on calm water. If this cannot be found outside the harbour, it is done in the harbour, only with the fore line on a windward bollard or jetty.

If I don't have anything to tie up temporarily, I use the following tricks: stop, lock the tiller, engage the clutch backwards. The boat now slowly turns into the wind with its stern and remains fairly stable. I also like to use this manoeuvre to wait for the opening in front of bridges or on similar occasions.

There are lots of little tricks that single-handed sailors can use to make their lives easier when travelling. But what will get them the furthest is to practise often and find out whether they really enjoy single-handed sailing, because only then will it all make sense.

Tips for single-handed sailors on seamanship and mental health

- Prospective single-handed sailors should get to know the boat they will be travelling with in all wind and weather conditions and check whether they are safe on the water even in challenging conditions. It helps to have fellow sailors on board for practice, who can intervene if necessary.

- Falling overboard when sailing single-handed in the open sea usually means certain death. Even a lifejacket won't help. It is therefore important to anticipate the ship's behaviour and movements and, if the conditions require it, to secure yourself with the lifebelt.

- Sailing manoeuvres such as reefing and changing headsails must be practised and mastered in your sleep.

- Repairing the equipment on board and improvising shouldn't be a big challenge.

- Preparation is a prerequisite for success. This includes finding out about the weather conditions. If strong winds are forecast, appropriate sails should be prepared.

- When planning the trip, also develop a plan B. Clarify the questions of where you can sail under jib, whether another destination on the day of departure might be more suitable than the one originally planned. One or more harbour days should also be included in the time budget.

- Driving at night has its charm, but also its very special challenges. And you can quickly end up in the dark unintentionally. So practise driving at night in pairs or threes.

- If possible, plan longer trips so that foreign harbours can be reached in daylight. If necessary, start at night.

- Deal with sleep management in good time. This is more difficult on the busy Baltic Sea than on the expansive Atlantic. Hallucinations are the rule after long periods of wakefulness. You also have to be able to deal with this. Plan recovery phases in good time, at anchor or underway with correspondingly short sleep phases. Realistically assess how long there is no danger of colliding with other ships. Test beforehand whether you really wake up from the alarm after 15 minutes of deep sleep. Try out under supervision how long you can stay fit enough with this intermittent sleep.

- Enlist the help of others if necessary. If there is a lot of wind in the harbour, make it clear that you are travelling alone and could use a helping hand. This can be done by shouting or signalling.

Converting a yacht for single-handed sailing: