Oh my! It's best not to talk about a model boat in connection with the Colin Archer construction that Klaus Steinlein from Bermatingen on Lake Constance built himself. "It's not a model boat, it's a flawless ship!" is his confident view. It is intended to give the impression of a real yacht, especially from a distance. In fact, there are hardly any details on board that go beyond the functional. There are no portholes or a scaled-down anchor windlass. And above all: the supposed model boat can be sailed, even if only with one person on board.

The ship looks like a model, but is not one

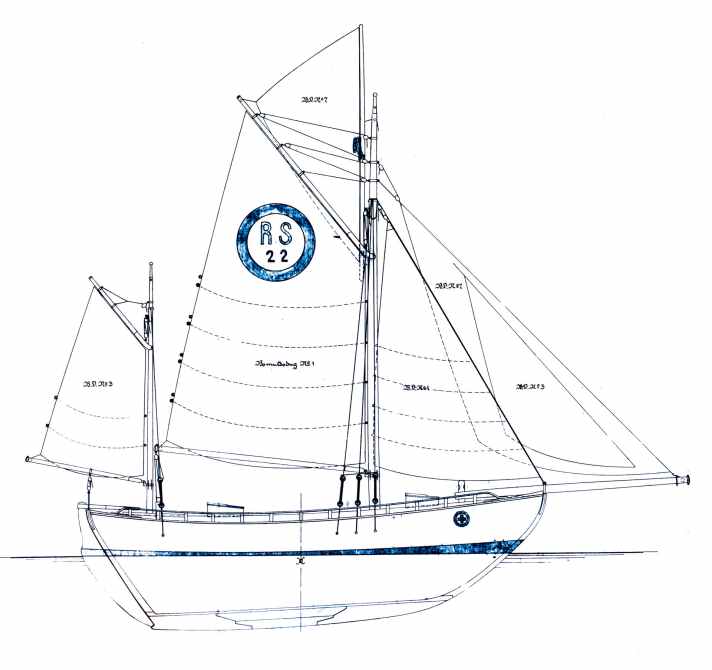

However, Steinlein's classic is small, or to be more precise, this characteristic double-ender with its hull length of 3.56 metres is one of the tiniest of its kind, possibly even the smallest manned representative of the legendary Colin Archer ships ever, the tiny, perhaps tiniest two-master.

Other interesting classics:

One step down from the jetty and you're on board. Caution! "It's best to only put weight amidships, the hull is already quite slender, there is practically no initial stability," warns the self-builder. The bonsai boat is a long keeler, yes, but only a tiny one. Only the ship is scaled down, the crew is the original size. Encouraging look from the builder. So don't hold on to anything, but take a quick step down into the cockpit and settle down on the cushion. Now the boom can swing freely above the head of the only possible crew member.

The yacht and construction idea immediately bring to mind the Mecca of all captains of mega cruise ships, ultra-tankers and giga container freighters: it is located north-west of the French Alpine city of Grenoble, 663 metres above sea level, 200 kilometres from the nearest coast. At the "Port Revel Shiphandling Center", four-strip captains train ocean liner encounters in canals, entering locks in swells and crosswinds or the "Williamson Turn", a kind of skidding turn for hundreds of metres long commercial ships - looking out of exactly the same deck hatches with coaming and with 1:25 scale units. Container giants thus shrink to 15 metres, yet displace 15 tonnes. Their "engines" are also to scale; the captains have to make do with electric motors with a power output of just 0.3 horsepower.

The classic is a miniaturisation based on a large model

Klaus Steinlein's small ship project is just as much like a trial and error, a test on a smaller scale, as a test of his boat-building skills for something bigger. And after all, his ocean-going construction has so far only travelled on inland lakes, his private "Port Revel". Steinlein's divisor is 4, so his classic "Mini Colin Archer" measures 3.56 metres instead of the 14.25 metres of the original plan, from the sturdy bow to the bold stern with its characteristic second, tapered stem. The reason for the reduction in size: the whale-like shapes of the Colin Archer pointed gates had and have simply taken a shine to him. That's what a yacht should look like, and it should be self-built! But the plans for these sturdy ocean-going yachts are always for larger chunks. The money for a full-scale model was not available at the time, not to mention the building site and the time required.

Klaus Steinlein was studying aerospace engineering in Munich 40 years ago when he caught the Colin Archer virus. The infection sent him into a fever that infected an entire fan community. The clinical picture: having to own such a classic at all costs. Those affected heard a kind of siren song of the greatest shipbuilding harmony - attempts at treatment were futile.

The designer is impressed by Colin Archer models

"I've always liked the mini twelve-wheelers. Then, on a sailing trip off Norway, I discovered a crucial book," says the self-builder, explaining his initial infection: "Colin Archer - the seaworthy Double-Ender" by John Leather. "There are quite a few plans in there and how they came about." Steinlein visited the Norsk Maritimt maritime museum in Oslo and took photos of the Colin Archer models there, especially of the details. "I then sent a letter from home to the people at the museum asking for plans."

He got them, had glass slides made of the blueprints and projected them onto the garage wall, an inexpensive and practical method at the time to achieve the desired 1:4 scale. For his GRP negative mould, he assembled frames made of spruce overhead on a straight slipway, with a crooked tour. "I often had to move my mini boatyard. So I stripped a shopping trolley of its four wheels and screwed them under my slipway so that I could move it." The first boatyard location was the parents' garage in Munich.

He planked his positive mould there from strips just five millimetres thick. "For lack of money - thicker ones would have been better in hindsight. Then I filled and sanded and sanded and sanded. You can sand it forever, it never gets really smooth." The semi-finished product was then delivered to a boat builder. He needed some space and simply manoeuvred it out of the hall. "The rain wasn't good. I had to fill and sand and sand again."

The mini glider has special features

Brief perplexity on board the now 30-year-old classic long keeler. How does the steering work? "Like the rudder of an aeroplane," explains Klaus Steinlein, as if everyone had already sat in a pilot's seat. Mini twelve-wheelers are also steered by foot. Using genoa rails and an ingenious cable guide from glider construction, the control cables running port and starboard from the body to the aft remain taut in any length setting. The feet are placed on pedals, pressing right means travelling to starboard. Oh my! The kick-out is far too strong at first, you can't pedal like you would when riding a bike.

Fortunately, the harbour exit off Fischbach on Lake Constance is not scaled down as in Port Revel and offers enough space to get into the open water, initially staggering and with a drunken course of the newly trained foot helmsman.

Once you've got the hang of it, you'll soon be able to hold your course sensitively and steer into the wind. And now it becomes clear that this is not just single-handed sailing, but even zero-handed sailing. Both hands are free, resting comfortably on the side decks, towing when heeling in the turquoise waters of Lake Constance or operating the, well, control centre consisting of six comb clamps between the chest and mast. When tacking, the jib and jib sheets have to be released from the comb cleats and placed on the new leeward side; they are practically a few finger widths apart.

The classic is easy to sail

The mainsheet and mizzen sheet can still be guided when dropping and luffing - sailing can be so simple! The mini Colin Archer is balanced on its tiny rudder blade and sails swiftly through the wind. In the gusts of the offshore breeze, the classic lies on its cheek with its topsail set. There's nothing to ride out, the bum slides to leeward. Within a short time, the initially uncomfortable heeling gives way to propulsion.

How fast? It soon seems irrelevant, so carefree and weightless is the sailing off the shore. It gurgles and gurgles under the helmsman's bum, feels like a rushing ride, bubbles whir aft at the hull window. A good four knots are measured for the record. But it would be inappropriate to make distance with this classic as long as distances and harbours are not also miniaturised.

The balanced rudder position is the result of careful calculations. "I knew how heavy the ship could be. I then had to calculate the displacement curve and determine its centre of gravity." Basically the same as in aircraft construction: weighing the most important components, counting squares in frame cracks and working out formulas. Steinlein: "I had a drawing board with the ship's plan and so I did the displacement calculations with my 85 kilogramme body weight, which is much heavier than the crew on the original yacht. So the ballast had to be placed further forward to compensate. From today's perspective, I have to say: well done!"

Building the mini Colin Archer requires many hours of labour

For the ballast, Steinlein poured plaster over the future site and moulded the resulting concrete parts. "Then I melted tyre lead and car batteries into it, a total of 180 kilograms. It was a mess." With a total displacement of 421 kilograms - with crew - this results in a ballast content of 38 per cent - the original, which is four times as long, has a ballast content of around 50 per cent. It was possible to build the boat lighter here, as it doesn't have the double rigging or the cabin fittings. Nevertheless, two frames had to be used for the finalisation, a beam walker now supports the plywood deck, painted ink strips indicate the rod deck joints and the colean paint applied at the time has not had to be renewed for 30 years. "I didn't have much social contact during this time; last year, the construction was already intensive."

The poles took three attempts. "In the beginning, I thought round timber would be suitable and bought two pieces for flagpoles. But it turned out to be knotty and warping wood." In the second attempt, Steinlein glued pine, but it was too heavy for him. "Then I used spruce from a cross-cut without a core, which is lighter." Three shrouds like the original, here made of 2.5 millimetre fine stainless steel wire, hold the masts in place with loops around the entire profile.

The mini classic stands out everywhere

The first mooring was an Ammersee buoy off Breitbrunn. The rowing boat Steinlein rowed out in was bigger than his yacht. He later moved the classic to buoys on Lake Starnberg and Lake Wörth - and it attracted attention everywhere. Even on Lake Constance. "Especially when there's a lot of wind, the water police often come by, usually travelling a little parallel - maybe they want to see if I'm okay. And if there's a lot of wind, I'm fine!" Even when the boat is heeling heavily, at most the side decks get wet. A hand pump is fitted, "but I've never used it before".

The wind is moderate today, but Lake Constance is still gushing through the openings of the railing with the horizontal wooden end, which is characteristic of Colin Archer constructions. Bathers swim towards with interest, swans seem to turn away in irritation, stand-up paddlers wave cheerfully. Sailing with this bonsai yacht feels safe and right - more length, displacement or sail area, no one needs any other yardstick at this moment. The yacht is - it's hard to believe - actually a success.

Steinlein remained loyal to wooden boats, managing an H dinghy, a gaff-rigged 15 dinghy cruiser, and has just completed the five-year refit of his 22 skerry cruiser. Even major work no longer worries him today. "For example, the forestay spar on my dinghy cruiser has knots that have become loose over time. I took them out and shafted them. That was hardly possible 60 years ago, you would have had to throw the spar away."

All work on board is carried out by hand

The wind is blowing from the harbour entrance, so it's time to cruise in with the imposing jib boom, which, even when scaled down, can alternately drill into the boats lying between the dolphins or the sheet piling. Later, Klaus Steinlein gives a tour of his basement workshop and explains the cones he has developed himself, which he uses to crimp brass tubes as line lead-throughs on the coaming so that the lines don't fray. "You just have to do a few tests to find out how much the tube needs to protrude. A bit of Uhu plus, sandpaper and varnish - a great thing."

On the shelf is a remote-controlled model sailing boat with a Flettner rotor. "I just wanted to try it out to see if it would work - and it did!" The smooth cylinder is driven by an electric motor to generate propulsion. The direction of rotation must be reversed at every turn.

Steinlein had tested the Mini-Colin-Archer at the time, but in return the boat also tested him. He passed his private boatbuilding exam a long time ago. So far, he has not overstretched himself with his projects and has been able to "scale up" his experience, as the start-up world refers to growing to scale today.

The walls up the stairs to the study room are adorned with numerous photos of his half-models, "winter works". One of them is another characteristic double-ender - the mini Colin Archer? "No. Now it would be my dream to build this pilot boat double-ender scaled down to six metres, which I now dare to do," says Klaus Steinlein, who has now rented a permanent hangar space in nearby Friedrichshafen, where he changes planks, renews paint and removes wooden masts in his spare time. In a way, his "Shiphandling Centre" is the equivalent of the French captain's school.

Technical data Mini-Colin-Archer

- Torso length:3,56 m

- Width: 1,21 m

- Depth: 0,57 m

- Displacement:0,42 t

- sail area:7,6 m²

- Ballast content:38 %

- Scale: 1 : 4

- Soaking: 1990

- Quantity: 2