Ocean Race Europe: 50 per cent increase - all about the Imoca class

The modern IMOCA yachts are catapulting themselves into a completely new dimension of sailing. Even the 2020 generation sailed around 50 per cent faster than the Open 60 monohulls from 2015/16 under optimal conditions - in half wind and flat seas. Speeds of 25 to 35 knots are possible. And the development continues: the latest designs start to "fly" earlier and stay on the foils for longer, even in rougher seas.

50 per cent increase in performance

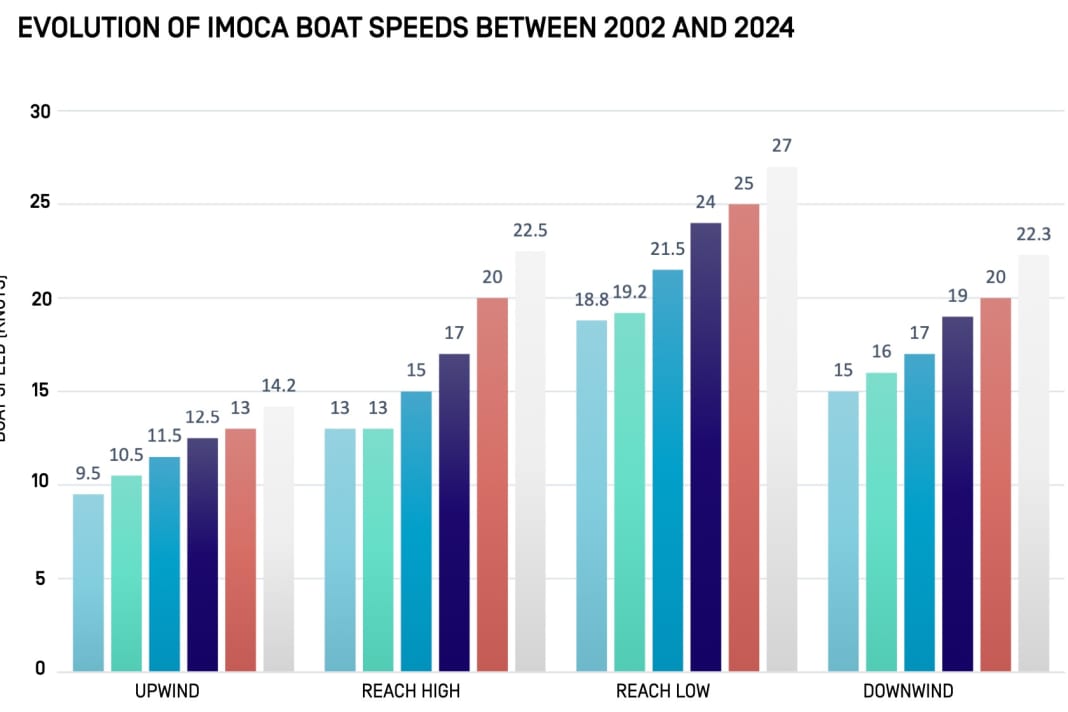

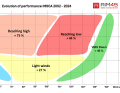

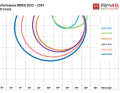

For a large-scale study, French sailor and performance expert Olivier Douillard analysed and compared the measured values of the best boats of all Vendée Globe generations since 2002. The result of his analyses: an increase in performance of almost 50 percent in the period examined! In addition to a significant improvement in top speed in almost all conditions and on almost all courses, there is another remarkable trend: the wind force required to reach a boat speed of 20 knots has dropped significantly over the same period. Whereas 20 years ago it took 30 knots, today only 14 knots of true wind are needed to achieve such speeds with an Imoca. You can find out more about the study here.

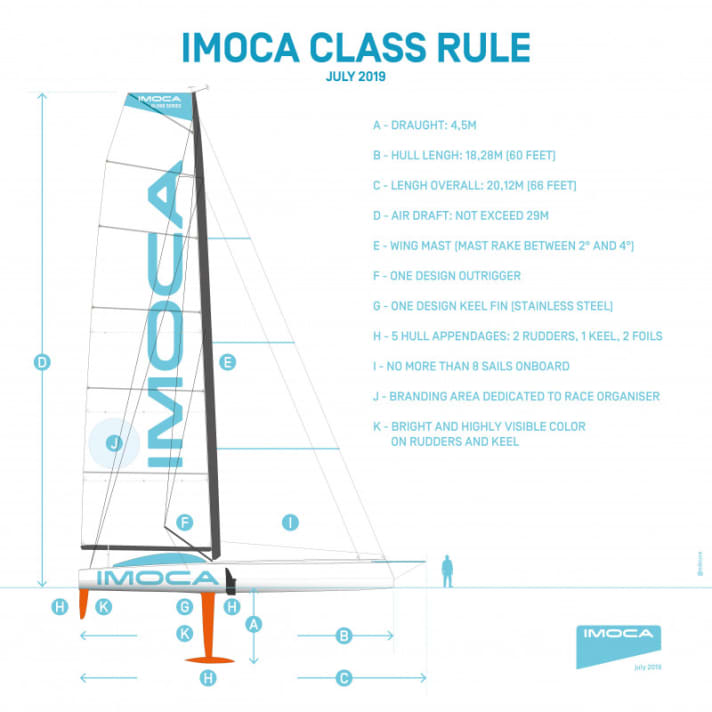

The class rules

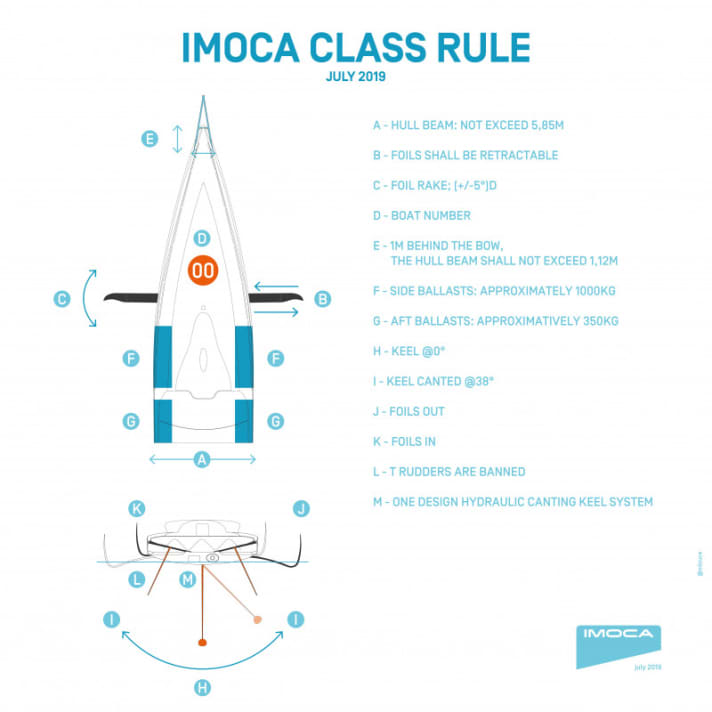

To prevent an arms race, the mast may only reach up to 29 metres into the sky and the keel a maximum depth of 4.50 metres. The ballast, whose minimum and maximum weight is also specified, can be swivelled to the side electro-hydraulically in order to use the weight more effectively. Even the angle is limited: up to 38 degrees to starboard or port, not one degree more.

20,000 to 35,000 working hours go into the development of a top boat, around 40,000 to 50,000 hours into its construction

In addition to the keel, an Imoca may use a maximum of four other attachments under water. In the latest designs, these are two rudders aft and two foils amidships - hydrofoils that lift the boat out of the sea at a speed of 12 to 14 knots, thereby helping to reduce water resistance.

These and other parameters are regulated by the class so that man and machine do not become a danger to themselves. Otherwise, designers, boat builders and skippers are relatively free in the design of the racing yachts. This is also what makes them so appealing - and their reputation as one of the most innovative classes of all.

In the beginning, before the first race in 1989, the technical rules were extremely simple. There were hardly any requirements. As a result, the International Monohull Open Class Association (Imoca for short) quickly became a haven for free spirits. This is still the case today, even if the degrees of freedom have been repeatedly restricted in recent years.

The design rules are an expression of a complex, sometimes erratic development. When almost anything was still permitted, there was a technical arms race at the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s that pushed designs ever closer to their physical limits, sometimes even beyond them.

As a result, spectacular failures became more frequent: Extremely narrow keel fins laminated from carbon fibre tore off, carrying ballast bodies weighing several tonnes at their ends, some of which were made from materials as exotic as tungsten. Masts broke in rows as they were designed to be lighter and lighter in order to develop less leverage. As the boats became increasingly wider and the superstructures ever flatter, some constructions remained keel up after capsizing, even in heavy seas. Several maritime emergencies forced skippers to be rescued by nearby competitors, helicopters or even naval vessels.

The cost of an Imoca

Another consequence of this inventiveness was a huge explosion in costs and an exorbitant drop in the value of boats from previous generations - neither of which was conducive to keeping the class attractive for less well-financed teams. Dizzying budgets in the millions combined with the growing risk of technical failures made it increasingly difficult for many skippers to find sponsors.

In order to mitigate these two trends, the Imoca class association, on whose committees the skippers have the say, but where designers, experienced team managers and marketing specialists also have a voice, gradually adopted new rules in a pioneering process from 2008 to 2013. Their aim: to enable innovation while avoiding excesses.

The members therefore decided to intervene at the design stage in future. To reduce costs, a standardised mast, a standardised keel and the necessary hydraulics were decided in 2013. In addition, they agreed on keel fins made of forged steel with a lead bomb, probably the safest and most durable solution to date.

A new Imoca building with foils costs 5-7 million

And yet: While a normal cruising sailor considers the keel of his yacht to be the most stable component that will last the life of the boat without grounding and hardly needs any attention, the underwater appendages of the Open-60s have to be regularly dismantled and serviced. They undergo extensive sonic or even X-ray examinations to check for the slightest damage to ensure that skipper and boat can sail as safely as possible. Nevertheless, there are always failures, at least in the hydraulics for tilting the keels, which is why all newer boats must have a device for fixing the keel in the neutral position.

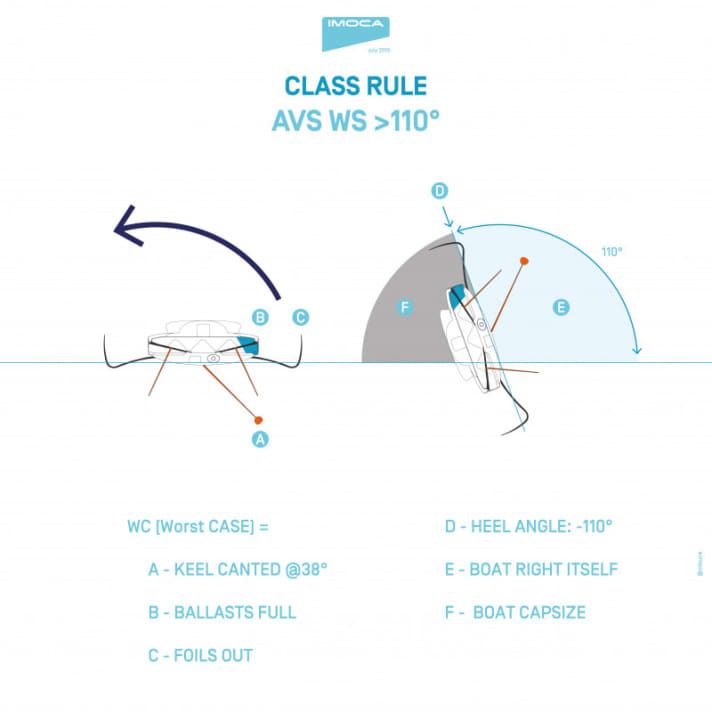

In order to solve the problem of yachts drifting upwards after capsizing, it was decided that the ships must right themselves up to an angle of 110 degrees. To do this, they undergo an elaborate test procedure:

The large teams have 35-50 permanent employees for the construction of a boat.

After completion, all new Imocas are moored in the harbour basin with the rigging upright and brought into a lateral position by a crane until the mast is horizontal above the water surface, at 90 degrees to the vertical. Electronic tension scales then statically measure how high the righting moment is at the top of the mast. Computer simulations are then used to determine other safety parameters that are important for approval. This and the subsequent calculations take several days. The shape of the hull and deck is also taken into account - this is one of the reasons why "Malizia" has a superstructure that extends all the way aft; this is intended to support the turning of the hull after capsizing and thus helps to save weight in the keel bomb.

There are also many other requirements set by the class. For example, the number of sails that may be on board during an Imoca regatta is limited: no more than eight sails are permitted. Even the maximum mast drop is limited. After the Vendée Globe 2020/21, it was regulated to between 2 and 6 degrees, which is intended to help minimise the bow dropping in the Southern Ocean when the boats are sailing at high speed into the back of large waves.

The same applies to the water ballast systems. Previously, some teams had up to eight trim tanks, which could be filled in seconds using valves while travelling. Now there are a maximum of six. The reason for this is that filling the tanks upwind causes the boat to develop a lot of additional righting moment, which can overload the structure and the single mast. The stern tanks are filled for room sheet courses where the wind blows from astern in order to lift the bow out of the swell via the leverage effect and prevent it from diving away.

The hydraulic cylinder of the tilting keel can withstand 40 tonnes of pressure

However, the foils have been the centre of attention since 2015. This is now the fifth generation of aerofoils, narrower and more expansive than before. There is a dimensionless upper limit for the area calculation that must be adhered to. However, the designers have come up with impressive and very different shapes.

They catapult the Imocas into a whole new realm. Even the 2020 generation sailed around 50 per cent faster than the Open 60 monohulls from 2015/16 in optimal conditions - with half the wind and flat seas - an unprecedented gain in ocean racing. Speeds of 25 to 35 knots are then possible.

And there is no end in sight. Because now the designs will start flying even earlier, and they should stay on the foils for longer, even in rough seas.

The Imoca members could not resist the temptation to optimise and further develop this new, exciting technology. After the brute performance of the boats had to be reined in for a long time, and after the previous generation of foilers had to undergo major structural improvements, it now looks as if a new evolutionary stage has been reached: flying earlier, longer, faster. Once again, the class underlines why it has such a legendary reputation - for being the world's most high-bred racing yachts on the offshore scene!

Limit dimensions of an Imoca

- Depth: 4.5 m max.

- Torso length: 18.28 m max. (60 ft.)

- Overall length with bowsprit: 20.12 m max. (66 ft.)

- Mast height: 29 m max.

- Profile mast: Carbon fibre wing profile, rotatable, maximum aft tilt adjustable from 2 to 6 degrees, one-design component

- Deckssaling: Carbon fibre, one-design component

- Keel fin: Steel, one-design component.

- Bomb: Lead, weight between 2.2 and 2.85 tonnes

- Underwater attachments: maximum 5 - 2 rudders (foldable), 1 keel (swivelling), 2 foils (retractable and rotatable)

- Sail: maximum 8 pieces, one mainsail, 7 headsails, aramid fibre laminates

- Colour: Rudder and keel in signal colours so that the ship can be seen more easily by rescue services when floating upwind in a storm

More about Boris Herrmann and the "Malizia - Seaexplorer":

Jochen Rieker

Herausgeber YACHT