He is, once again, at sea. Just as this issue went to press, Jean-Pierre Kelbert started the Cap Martinique Race, his fifth transatlantic regatta and third solo race across the pond, on the first weekend in May. The wiry Breton, who everyone just calls "JP" and whose initials characterise the JPK brand name, is, as always, one of the favourites. He owes his exceptional position to his unerring instinct for wind and waves, but also to the outstanding potential of his yachts.

In other words, that of most of his boats; almost all of them, to be precise - except for the one we are talking about here. That is different.

The majority of JPKs have been among the most universal and successful ocean racers for years. Initially, however, in the early 2000s, they were only known to insiders. However, since the historic first overall victory of a double-handed JPK 1010 in the legendary Fastnet Race 2013, the small, fine shipyard from Lorient has been regarded as the reference in IRC measurement when it comes to long-distance regattas and suitability for small crews. No wonder, really, with a boss who is also passionate about speed sailing in his private life.

Initially barely recognised by the competition, JPK has now firmly established itself

In the late 1980s, Jean-Pierre Kelbert was twice European surfing champion. When he had reached his sporting zenith, he founded JPK Composites in 1992 and specialised in building lightweight boards, which won many national and several world championship titles in addition to surfing records in the following years. Ten years later, he switched to yacht building - and promptly repeated his success story.

Initially barely recognised by the competition or at best denigrated as a "garage company", JPK has now firmly established itself. The boats are built in modern shipyards using a process that is far superior to the usual series production standard. The production areas cover a total of 4,000 square metres. They are located in Larmor-Plage, just one kilometre away from the most important ocean sports centre in the world, the former submarine harbour "La Base" in Lorient, which is home to many Ultime and Imoca skippers, including Boris Herrmann's Team Malizia, the German-Japanese racing team DMG Mori, Sam Davies, Isabelle Joschke and other acclaimed stars.

Also interesting:

If you consider the history of the shipyard, its sporting successes and its proximity to the international offshore scene, then the JPK 39 doesn't quite fit the picture. Because although the mast and railing supports are anodised in a slightly martial black, a 1.80-metre-long carbon buspipe towers over the stem at the front and two tiller posts are fitted in the cockpit instead of double helm stations, this is definitely not a regatta boat.

The name suffix "FC" alone promises a "fast cruiser"

A fixed windscreen spans the cabin superstructure, which is glazed all round in a similar way to deck saloon yachts. Three hull windows on each side allow a view to the outside from all compartments. However, below deck at the latest, where the crew will find a walnut interior that may not be opulent but is nevertheless inviting, you know you have arrived on a cruising boat. "It's a cruiser/cruiser," Jean-Pierre Kelbert emphasises mischievously to differentiate the design from the generic term racer/cruiser that is usually used for his models. A pure tourer, in other words. But according to the shipyard boss, "you can of course also have fun with it".

The name suffix "FC" alone promises a "fast cruiser", a speedy cruising boat. And this is how the JPK 39 fits into the shipyard's programme: as a hybrid with an unmistakably sporty heritage. It is the smaller of only two models with a comfort character. There is also the JPK 45 FC, which made its debut five years ago and is similar in many ways, not least in the cabin design - an otherwise rather subordinate discipline of designer Jacques Valer.

He is better known for exploiting the last loopholes in the IRC formula. Together with Jean-Pierre Kelbert and his right-hand man Jean-Baptiste Dejeanty, who is also a designer, Valer has created a saloon that you would want on every boat.

Unusual transparency thanks to generously dimensioned surface-mounted windows

It is not so much the layout that is unrivalled: The navigation and longitudinal galley are to starboard, the U-shaped seating area to port, with a room divider in between, which is also good for support when the boat is in a position. What is more impressive is the unusual transparency thanks to the generously dimensioned superstructure windows to the front and both sides.

At sea or at anchor, you can keep a constant eye on what is going on around your boat. This is both a safety-related and simply beautiful added value, which also provides plenty of natural light below deck. Only two aspects stand in the way: The boat heats up considerably on days with long periods of sunshine - partly because the number and size of the deck hatches is limited. In addition, from the outside, you have to live with the 15 millimetre thick Plexiglas strip, which gives the JPK a certain independence, but also a visual impact, especially as it tapers sharply towards the stern. You may find this modern, but it does not look discreet. Judged from the inside out, however, the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages.

Because both the deck and the superstructure have a markedly negative step, the boat offers sufficient headroom where you need it most, despite a moderate freeboard. The other dimensions are also impressive. The storage space in the standard version we tested adds up to 3.5 cubic metres, even without the technical room on the starboard side, more than half of which is easily accessible in cupboards or lockers. Compared to the average for performance cruisers between 36 and 40 feet, the berths are downright generous. A veritable double bed can even be created in the saloon if you order the lowerable table (extra charge).

The JPK 39 is also very light compared to the competition

In some details, the construction number one must be credited with a certain nonchalance in its workmanship. In the wet room, for example, the shipyard places beautifully veneered doors flush on a GRP inner shell, without frame timbers, without height levelling, without a visual connection. The gap that remains between the inner shell of the ceiling panelling and the sides of the hull is simply covered with loosely clamped black foam strips, which is light and practical, but on closer inspection is not aesthetically pleasing.

These limitations should not distract us from what really counts. Because that's what the JPK is exceptionally good at. The hull and deck are a complete sandwich construction, apart from the solid laminated keel suspension. The inner and outer laminate layers are bonded to a 25 millimetre Airex foam core using a vacuum infusion process, which offers very high strength values at a low weight.

The bulkheads are built in the same way and glued to the hull and deck and also laminated over. This also applies to the floor assembly and the furniture foundations, which also have a stiffening function here; they are firmly attached to the hull.

At 5.6 tonnes, the JPK 39 therefore remains very light. A comparable vehicle in terms of dimensions, but with a more luxurious interior X 4.0 displaces 8.1, the Dehler 38 SQ still 7.5 tonnes. Only the slightly smaller models are below this First 36 with 4.8 and Pogo 36 with an unladen weight of 4.2 tonnes. This has a very positive effect when sailing. Without wishing to diminish its inner values, it is this discipline in which the JPK is most convincing. Even in light to medium winds - exactly the conditions that cruising sailors appreciate the most.

Not overly spirited, but in keeping with the character of a brisk cruising boat

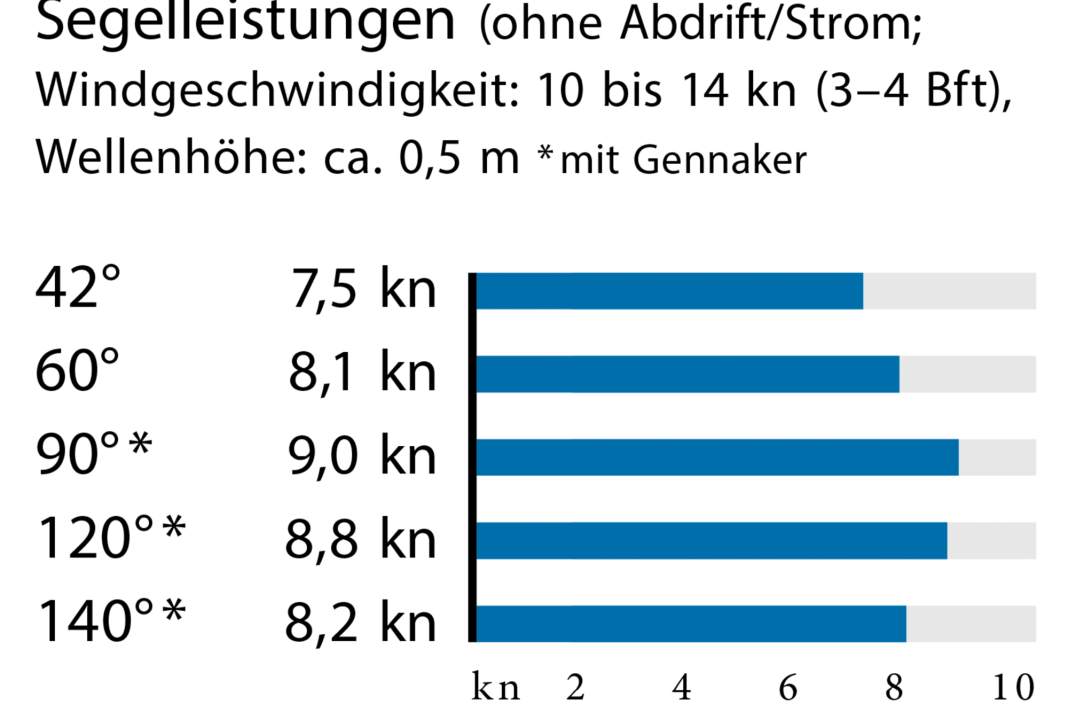

Two Beaufort is enough to prevent any thoughts of the built-in diesel engine, especially as it is acoustically rough and quite loud. In 6 to 8 knots of wind under main and genoa, the Frenchwoman averages 6.5 knots through the water. She is already sailing at around 45 degrees.

In 10 to 14 knots of wind, she logs 7.5 knots; the tacking angles shrink from around 90 to a very good 80 to 84 degrees. When a front comes through and it builds up to 20 to 24 knots, the JPK 39 proves its high degree of stability. This is not only due to the high ballast ratio of 34 per cent and the low centre of gravity, but also to the large width in the waterline. This means that she can still carry full rigging with a hard backstay, a flatter genoa centre of gravity and a lowered mainsheet traveller. The stiffness is particularly noticeable on half-wind courses. It remains predictable and under control even in conditions where rockered constructions become nervous or even bitchy.

On average, we reached 12 knots through the water during the test, with a peak of over 13 knots. This may not be overly spirited; the Pogo and First 36 sail faster and accelerate more brilliantly. However, it fits in with the character of a fast cruising boat that carries its crew with vigour, not demands it.

Rightly Yacht of the Year 2022

For most owners, what will be more important than top speed is how early and therefore how long the JPK starts planing. Under the large top gennaker with a sail area of 138 square metres, 12 knots of wind are enough for her to reach a sustained speed of 9 knots. This creates a highly attractive equilibrium of forces that seems almost effortless. Properly trimmed, the helmsman can let go of the tiller for minutes in this floating state. The more luxuriously furnished but heavier competitors can no longer keep up.

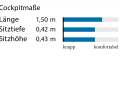

And it's not just the speed or the relative ease with which it can be called up. The JPK also impresses with its highly efficient cockpit design. In principle, Jacques Valer and Jean-Baptiste Dejeanty have transplanted the workplace of their regatta yachts into the stern of the sports tourer.

The helmsman sits on the side deck behind the 1.50 metre short thwarts and a good half metre in front of the traveler, which is bolted all the way aft, so that the mainsheet does not interfere with manoeuvring. There he has direct access to the tiller, as well as to the backstay, traveller, main and genoa winches. The headsail can be easily redirected to the windward winch for solo operation.

This concentration is fun because the JPK can be operated almost blindfolded after a little familiarisation. Individually adjustable footrests also ensure a secure hold. There is only one drawback to the arrangement: there is quickly quite a lot of rooting between the tiller seats. On the other hand, the front part of the cockpit remains largely untroubled by sheets and control lines.

For a crossover model that, by definition, demands a willingness to compromise, the JPK really doesn't show its hand anywhere. This is why it won the coveted boatbuilding Oscar in its class at the end of January 2022 against top-class competitors. She does everything right in terms of sailing and almost nothing else wrong. Chapeau, JP!

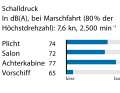

The measured values for testing the JPK 39 FC

The JPK 39 FC in detail

Technical data of the JPK 39 FC

- Designer: Jacques Valer

- CE design category: A

- Torso length: 11,65 m

- Total length: 11,72 m

- Waterline length: 11,00 m

- Width: 3,98 m

- Draught/old: 2,15/1,80/1,30-2,70 m

- Mast height above WL: 18,07 m

- Theor. torso speed: 8.1 kn

- Weight: 5,6 t

- Ballast/proportion: 1,9 t/34 %

- Mainsail: 44,0 m2

- Furling genoa (110 %): 38,0 m2

- Machine (Volvo-P.): 21 kW/28 hp

- Fuel tank: 90 l

- Fresh water tanks (2): 180 l

- Faeces tank (1): 50 l

- Batteries: 1x 100 Ah + 1x 75 Ah

Hull and deck construction

GRP sandwich with Airex foam core, vacuum infusion process, laminated with vinylester. Sandwich bulkheads. T-keel with cast iron fin and lead bomb

Equipment, price and shipyard

- Base price ex shipyard: 296,490 € gross incl. 19% VAT.

- Standard equipment incl.: engine, sheets, railing, navigation lights, battery, compass, sails, cushions, galley/cooker, bilge pump, toilet, fire extinguisher, electric coolbox, waste-holding tank with suction system

- For an extra charge: Laminate sails (main and genoa), genoa furling system, sail clothes, anchor with 60 m chain, fenders/ mooring lines, antifouling, clear sailing handover

- Guarantee/against osmosis: 2/2 years

As of 05/2024, how the prices shown are defined can be found here!

Included in the price:

Extendable carbon fibre bowsprit, 3D lifting point adjustment for genoa sheets, two-blade folding propeller, panoramic glazing in the saloon

Electronics as required

Owners can choose between NKE or B&G for the instruments and autopilot. Customised configurations are possible. There are no standard packages in the price list.

Batteries depending on requirements

In the basic version, the battery capacity of just 100 Ah is barely sufficient for longer trips. However, two lithium batteries with 100 Ah each are available for an additional charge.

Motor with extra power

Instead of the rather tightly designed Volvo Penta, the test boat came with the more powerful but rustic 38 hp Nanni. Surcharge.

Rig made to measure

The JPK is available with a black anodised aluminium mast or Axxon carbon rig. Shrouds and stays optionally made of wire, Dyform or rod.

Shipyard

JPK Composites is based south of Lorient in Brittany: ZA de Kerhoas, 56260 Larmor-Plage. Tel. (0033) 2 97838907, www.jpk.fr

YACHT review of the JPK 39 FC

Anyone ordering a JPK 39 Fast Cruiser today will have to wait three years. No wonder! In the 38-foot class, Europe's yacht of the year 2022 is one of the most universal performance cruisers - thanks in part to the superstructure's functionally successful all-round glazing.

Design and concept

- + Ideal sports tourer

- + High-quality GRP construction

- + Good view from the lounge

- - Expensive; no dealer network

Sailing performance and trim

- + Easily retrievable potential

- + Early gliding ability

- + High stability

- + Very good one-handed suitability

Living and finishing quality

- + Practical cabin layout

- + Good usable technical room

- + Comfortable berth dimensions

- - Partly simple surfaces

Equipment and technology

- + Well dimensioned fittings

- + Torsion-resistant structure

- - Rudder deflection on test boat restricted to starboard

The article first appeared in YACHT 11/2022 and has been updated for the online version.