Cape Horn - a name like thunder, a synonym for hardship and danger. The weather conditions are brutal: cold, wet and sudden changes in the weather make the place one of the most inhospitable corners of the seven seas. In winter, there is a risk of collision with icebergs. Due to the prevailing westerly wind drift, the passage from east to west can be a hell of a ride. Cape Horn is home to the largest ship graveyard in the world. Over 800 ships sank there and 10,000 sailors found their watery graves in the area. It is the most significant of the three great capes. A myth that still frightens and fascinates people to this day.

Cape Horn gets its name

The first ship was lost before it had even reached the Cape: a fire broke out on the "Hoorn", in which a Dutch expedition crew led by Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire had sailed safely to Patagonia, during repairs shortly before reaching its destination and destroyed it.

The two captains Schouten and Le Maire came with the task of finding an alternative route to the East Indies Spice Islands, as both the route around the Cape of Good Hope and the Strait of Magellan, which had already been discovered in 1520, were controlled by the Dutch East India Company.

The city of Hoorn had financed two ships for the planned excursion, which was to break their monopoly: the "Hoorn", which gave the cape its name, and the "Eendracht", on which the crew continued their journey after the loss of the other ship. In addition to the famous cape, Schouten, Le Maire and their men mapped other previously unknown islands. But it was the discovery of the passage around the southern tip of the American continent that put them in the history books at the end of January 1616.

Cape Horn remains impregnable for a long time

Until the beginning of the 19th century, the area around Cape Horn remained a relatively little-travelled shipping route. The wind, currents and, above all, the fast-approaching storms were too dangerous, and the square-rigged sailing ships that were common at the time were too sluggish and could not really be used to cross.

Countless captains have failed in their attempts to round the Cape. Captain William Bligh tried for four weeks in 1788 with his "Bounty"; then the never-ending storm forced him to turn back. Although 10,000 nautical miles longer, the route to Tahiti around the Cape of Good Hope seemed a better alternative.

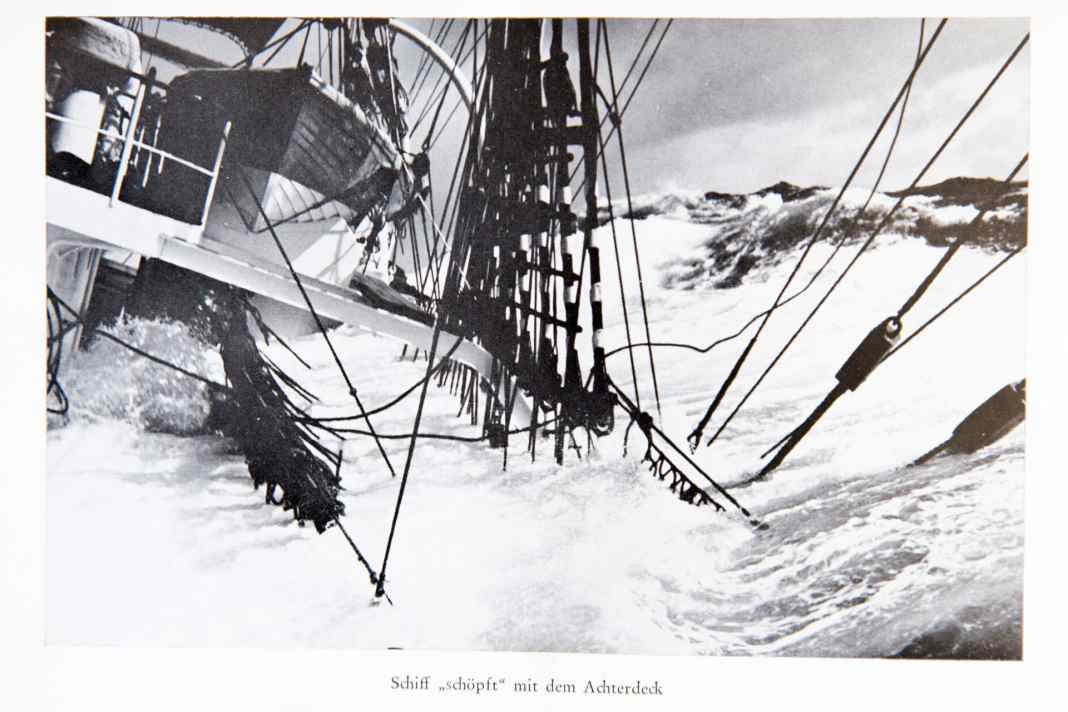

Those who nevertheless managed to get their ship and crew round the Cape from east to west in the icy winter often paid a high price.

The longest circumnavigation - counting from the 50th to the 50th parallel - was completed by the full-rigged ship "Susanna" in 1905: it took her 99 agonising days. When she arrived in Caleta Buena, nobody expected her to make it; there were only eight men left on deck, the rest of the crew lay in their bunks with broken limbs, typhoid or scurvy. Nevertheless, miraculously no one died on this hellish journey.

The fate of the "Admiral Karpfanger", on the other hand, remains uncertain to this day: the four-masted barque presumably collided with an iceberg in 1938 and sank. Only a door and a few pieces of wood were later washed ashore in Tierra del Fuego. Not a single one of the 60 crew survived.

The legendary record around Cape Horn

The route around Cape Horn gained in importance with the start of the saltpetre voyages in the 19th century. European shipping companies deployed cargo ships that loaded saltpetre on the coasts of Chile. This was in demand in Europe as a fertiliser and for the production of explosives. The so-called Flying P-Liners of the Hamburg shipping company F. Laeisz became world-famous on these voyages. And so it was a Laeisz ship that still holds the record for the fastest rounding of the Cape from east to west: In 1938, the four-masted barque "Priwall" raced round America's southernmost island in just five days and 14 hours.

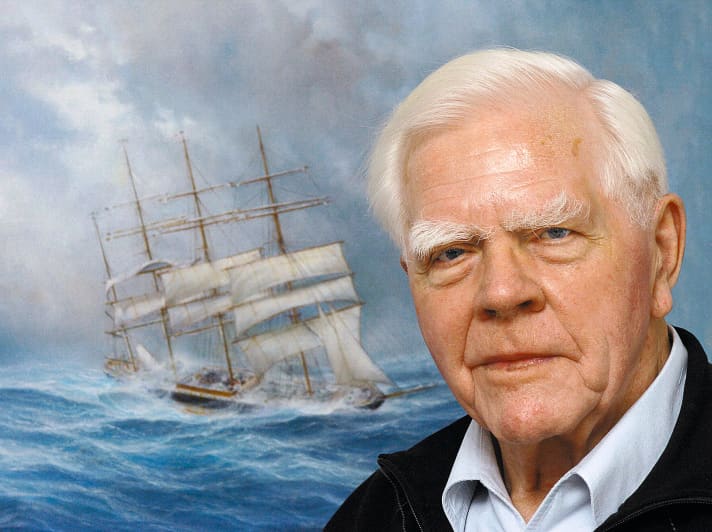

When the future captain and marine painter Hans Peter Jürgens joined the "Priwall" as a ship's boy a year later, the conditions were far worse. He was told by his captain that God had created Cape Horn in wrath. With burst fingers and skin chafed by oilskins, he serves in the yards. His only goal: to survive. A sailor's adage burns itself indelibly into his memory: "If you want to grow old, avoid Cape Horn and hoist the sails in good time."

The last cargo ship to pass Cape Horn without an auxiliary engine was the "Pamir" in 1949. This marked the end of the great era of cargo ships; steamships and motorised vessels replaced the legendary Flying P-Liners. In addition, a safer route from the Atlantic to the Pacific had been available since 1914 in the form of the Panama Canal.

The sailors discover Cape Horn

Nevertheless, the most unpredictable sea area in the world has never lost its fascination. The first US private yacht to round the Cape on a westerly course was the "Coronet" at the end of the 19th century - an exceptional achievement that made her famous. It is only since the 1970s that more and more leisure skippers, circumnavigators and adventurers have been sailing around the Cape, and today it is they who keep the myth alive.

Not all of them pass the rock unscathed. The equipment and weather forecasts are much better than in Schouten and Le Maire's time. But ships are still lost and people remain at sea. For example, the "Ole Hoop", which was lost in 2002 on its second round-the-world voyage about 100 nautical miles west of the Cape. There is still no trace of the owner couple Klaus Nölter and Johanna Michaelis.

The story of Miles and Beryl Smeeton is as dramatic as it is curious: they capsized twice with their "Tzu Hang" in 1956 and 1957 in almost the same place and lost the mast both times. It was not until ten years later, in 1968, that they managed to round the horn.

When Wilfried Erdmann crossed the Cape single-handed for the second time in his life in 2000, he did it the hard way, from east to west. In the Le Maire Strait, he notes: "I look into the milky darkness with a mixture of fear and hope. I can't detach myself from what's going on around me. I get an idea of what it's like to sail into nowhere, pushed by a powerful current and a wet storm wind. Spooky. A rock is coming, a waterfall, the end." It doesn't come, thank God. But Cape Horn leaves its mark on everyone.

Regatta sailors also conquer Cape Horn

Some of the toughest regattas in the world pass Cape Horn. Boris Herrmann has just rounded the Cape with his "Malizia - Seaexplorer in The Ocean Race.

In the Volvo Ocean Race 2014, Team Dongfeng's mast broke 240 nautical miles off the Cape in darkness and 30 knots of wind.

The rescue operation for French professional Jean Le Cam in the 2009 Vendée Globe is legendary: around 200 nautical miles south of Cape Horn, he finds himself in distress when his Open 60 "VM Matériaux" loses the keel bomb, capsizes and drifts keel-up. Le Cam waits for almost a day in an air bubble below deck. The Epirb is released and a freighter sets course for the shipwrecked vessel, but is unable to intervene due to the rough seas. Finally, his rival Vincent Riou rescues him in a dramatic operation: he needs four attempts, during which his own boat "PRB" is so badly damaged that the mast breaks shortly after rounding the cape.

Hamburg offshore professional Jörg Riechers experiences the Cape as a "forecourt to hell" during the Barcelona World Race 2015. A tropical depression develops into a "meteorological monster" shortly before the rounding - 951 hectopascals is the devastating forecast. That means a severe hurricane and waves of up to 15 metres. Riechers and co-skipper Sébastien Audigane try to get ahead of the low pressure to avoid the worst of it. And it seems to work: They pass the cape in a rather moderate 35 to 40 knots of wind.

When the two deep-sea pros already have the rock in their wake, disaster strikes: a 70-knot gust hits their Open 60 "Renault Captur", almost throwing them onto the next rocky island. For six hours in 50 to 70 knots of wind, boiling seas and 25 knots of speed, Riechers and Audigane are in a state of euphoria, nervousness and joy. Once they had survived, they breathed a sigh of relief: "We made it! Passed Cape Horn and alive!"

"On the hard road"

One of the last Cape Horners, Captain Hans Peter Jürgens, rounded Cape Horn as a 15-year-old ship's boy on the four-masted barque "Priwall". He recounted that memorable voyage for YACHT in 2016. He died in 2018 at the age of 94.

Mr Jürgens, your father was a captain himself. Although your parents were not particularly enthusiastic about you going to sea, your father put you on the Flying P-Liner "Priwall" in 1939. When did you first hear about Cape Horn?

For the first time as a child. My father didn't talk about it himself, but I heard about it from the crew members on board his ships. Later, on the "Priwall", not much was said about Cape Horn. What I remember most from the old days is Captain Hauth's memorable sentence: "God created Cape Horn in anger."

YACHT: How did you feel when you first passed this notorious rock at the age of 15?

The experience of rounding Cape Horn in the stormy southern winter was the beginning of my seafaring career. It was a personality-shaping experience for a 15-year-old: realising what hardships you were able to endure and what you were capable of. And that you could rely on your shipmates.

YACHT: What does Cape Horn mean to you?

I can claim to have circumnavigated the Storm Cape for the last time the hard way, from east to west, as the youngest person on board a cargo sailing ship.

The article first appeared in YACHT 3/2016 and has been revised several times.