The anchor is dropped after a beautiful day of sailing, a simple meal is eaten in the cockpit with a view of the sunset, and then it's off to bed early, as exhausted and happy as only sailors can be. It's not unusual to wake up in the middle of the night to the sound of a buzzing backstay or a beating clubstander when the wind suddenly picks up. Then it's barefoot and freezing on deck to identify the source of the noise and calm down. After that, however, the tiredness is gone for the time being, and with a particularly keen ear, even the quietest rigging noises are now perceived.

Minimise rigging noise: Here's how

What a lot of rattling, humming, whistling, rattling and humming in the wind! As a long-standing owner, you know every noise and its cause immediately. With a new or chartered boat, the only thing that helps is a planned approach, preferably in daylight, before you go to bed.

This is because many things from the deck up into the mast can become a source of disturbing noise. The classic example is the halyard hitting the mast. If the main halyard has not been cut off and attached at a considerable distance from the mast, for example to the boom clew or the pushpit, it should at least be tensioned away from the mast with a pointer. The spinnaker halyard and topping lift are also often shackled to the jib iron. Here they do not interfere with manoeuvring and maintain a certain distance from the mast. However, if the wind picks up strongly, this may not be enough, especially higher up, and it can still beat. The distance must then be increased, for example with an attachment point on the foredeck, on the pulpit or a deck eye.

Noise development annoying, material suffers

In a lonely anchorage, the clattering only wakes up your own crew, but in the harbour it keeps many other crews in the vicinity awake. The halyard is therefore just one of many points that should be checked when clearing the yacht after the trip. For example, the headsail cover. It protects the valuable fabric from harmful UV radiation. However, if the cover is not pulled tight, it will flap annoyingly in the wind. Not only is the noise annoying, but the tarpaulin and sail also suffer enormously from the friction. The flapping can also cause the entire rigging to swing up. Then there are noises that may not seem particularly loud on deck, but make all the more noise below deck. These can be rattling cables that are knocked against the profile in the shaking mast.

It helps to calm the source of the strong vibrations (the flapping tarpaulin), but the cables should also be laid in such a way that they can strike as little as possible. A cable duct can help here. However, if it is already full and a new cable needs to be laid, this should be taken care of immediately: This can be done with cable ties, which are attached in a star shape and act as spacers to the profile every 50 centimetres along the cable.

But even this alone does not always help, because the mast can also swing up due to the draught and buzz on its own, even if there is no additional cable or halyard. In this case, several measures together can restore a good night's sleep: A fender, pulled into the mast, has a positive effect on the airflow, more or less backstay tension and an improvised baby stay with the topnant on the foreship cleat stop the swaying. It may be necessary to play with the height of the fender in the rig and the tension of the stage until calm returns.

Striking traps in the harbour

When it is nice and quiet on board, the halyard on the neighbouring boat rattles: Bing, bing, bing! The owner may have moored with little wind, left, and now with more wind the main halyard is banging deafeningly. Can or should you go on board and tie off the halyard? Getting on board another person's boat unloaded is actually forbidden. And just because you're annoyed by the slight rattling doesn't automatically make you an exception to this rule. Or does it? At the latest when the noise is compounded by a problem that causes damage to the neighbouring boat or even your own boat, action is called for.

A fluttering and slowly unfurling genoa can quickly hit your own rig if you are moored downwind. If the headsail is furled so far that a few turns of the foresheet enclose the sails and the furling line and sheets are firmly secured, the owner of the neighbouring boat will certainly thank you. Or if flapping halyards cause the rig to vibrate to such an extent that an unsecured shroud tensioner shakes loose, intervention is definitely required. The first thing to do is to contact the harbour master. However, if the problem only becomes apparent late in the day or in the middle of the night, then in such an extreme case, action may even be necessary. If there is only one case, you could argue with a wink that you are preventing greater damage by not focussing the general displeasure of the surrounding crews on this boat. And no damage is caused if a halyard is shackled to the spinnaker fitting or sail head and reattached to the railing, well away from the mast.

It is exciting to track down noises that are not audible on deck. However, they can be all the more noticeable below deck. Even small straps on the railing - with a plastic hook to secure the gennaker bag, for example - can cause loud clicking noises in the saloon. In this case, it is helpful to attach the tether or elastic band under tension so that it no longer strikes anywhere. Halyards that are secured at a common point can also bang against each other. This is almost inaudible on deck as there is no resonance chamber like the mast profile. However, the vibration is then transmitted via the deck eye or the pulpit below deck, where it can be very disturbing. This usually happens when the lines are very tight. If there is a little slack, there is no force and they do not swing up rhythmically.

Rigging noises at sea

But excessively loud rigging noises can also be a nuisance at sea. Metal shackles on the clew of the genoa, for example, cause loud impacts on the mast when tacking. Not only does this sound martial below deck, it also goes hand in hand with the certainty that every manoeuvre will leave scratches. That doesn't have to be the case. Simply attach the sheets with a bowline or a soft shackle, preferably even spliced into the sheet, and there will be less wear and tear.

Dyneema aft and backstays also tend to be a source of loud humming at sea. As light as the material may be, it can also be very loud under load. Here, rubber bands wound in a spiral around the jetty over a length of around 1.50 metres ensure significantly reduced vibrations and therefore less noise.

Flapping leeches are also an extremely annoying source of noise under sail. The solution of slightly pushing through the leech tape actually falls into the category of sail trim, but ensures peace and quiet and also protects the cloth from serious damage. Double benefit.

Rig calming sounds in a storm

Apart from undisturbed sleep and the widespread desire to have peace and quiet on board, there is another special case for rig-soothing measures, and that is storms in the harbour. From wind speeds of 30 knots or more, whistling and rattling can no longer be avoided. Then it is no longer a question of reducing disturbing noises, but of protecting the material from damage.

As this also applies to the time when the yacht is unmanned in the harbour, every time you leave the boat you should proceed as if you, as the owner, wanted to be able to sleep in peace below deck. In extreme cases, in the event of a severe storm, further precautions may be advisable. For example, taking down the genoa if the hull can hardly be pulled tight enough even in light winds. In an emergency, the mainsail cover can also be wrapped with a mooring line to provide additional protection against flapping or even blowing away.

The fender in the rig can also be rather counterproductive in stormy conditions and can hit more than reduce vibrations. In this case, the variant with the shock absorber on the forestay is definitely preferable.

Apart from these special measures, it makes sense to consider a routine that suits the boat when clearing up after the trip. Where do the halyards get in the way the least and don't beat, what tension on the mainsheet and backstay is ideal to prevent the mast from swaying, are the lazyjacks tied far enough away and is the headsail cover tightened enough?

Because the fresh breeze is bound to come in the middle of the night from time to time. And if all the causes of rigging noises have already been eliminated, you don't have to go on deck barefoot and freezing at night.

Reader tips for peace and quiet in the rig

Tip 1: Bommel on the Dirk

Changing the air flow helps to prevent the humming of stationary or moving goods. One reader achieved this with a bobble. To do this, two cardboard discs with a large hole in the middle are slit so that they can be pushed over the dirk. A woollen thread is then looped around the discs. Then cut the wool along the discs and fix it with a few windings between the discs.

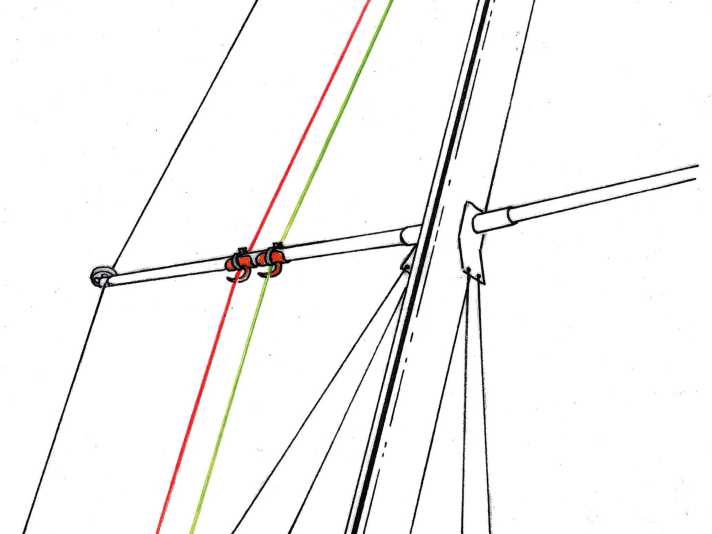

Tip 2: Hook on the spreader

Release the halyard, swing it behind the hook and tighten it again. It's that easy to tie the line away. The hooks can either be improvised from towel holders, as in this reader tip, or bought from specialist dealers as halyard deflectors from Pfeiffer. This quickly ensures peace and quiet in the rig and eliminates the need for a Zeiser to tie away the halyards.

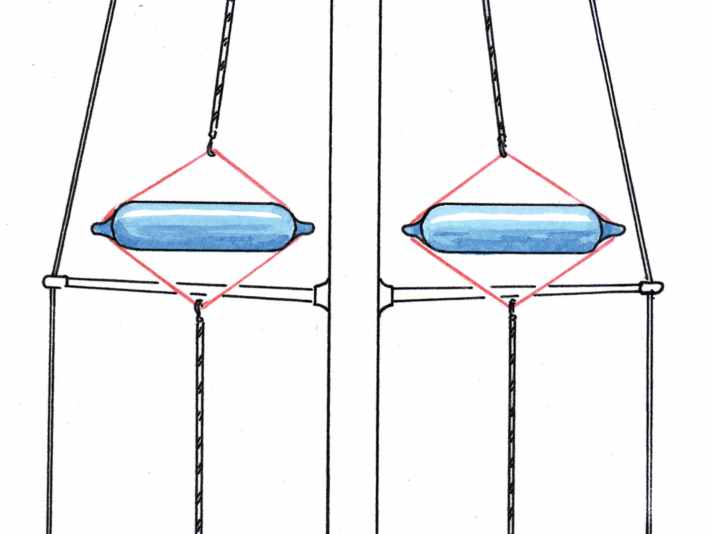

Tip 3: Two fenders in the mast

The fender on the mast, which is supposed to reduce the humming and rattling, is well known. This reader tip goes even further and suggests not only two fenders, but also horizontal ones. This is achieved using a tap pot above and below the bumpers. Positioning is crucial. Because if the fenders hit the spreaders, this can be even louder than the humming mast without fenders. A little experimentation is required to find the right position in the rig.