Sailing around the world 1973-1975: Four Hamburg residents live their sailing dream

YACHT-Redaktion

· 10.03.2024

- Inspired by Wilfried Erdmann and the Koch couple

- An alternative way of life at sea

- Analogue navigation, no night watches at sea

- In the Caribbean, they meet British celebrities and Princess Margaret

- Sartre and Camus, The Who and the Stones as a distraction

- Writing the experience reports together becomes a fundamental debate about the experience

- Sensual time in the South Seas

On a sunny morning in July, around 80 predominantly young people are standing on a terrace high above the Elbe in Hamburg-Blankenese with cocktails in their hands. The men are wearing chequered shirts, flared trousers and long hair. The women mostly in pleated skirts or fancy dresses. They have come to say goodbye to their four friends: Nikolaus Hansen and Heinz Lehmann, both 21, inseparable since they started school. And the brothers Thommy, 24, and Rainer Habekost, 23, also best friends. The four of them want to leave that very afternoon.

There is a film of the events on the terrace. It shows laughter, loud debates, in between quiet, intimate hugs. Excitement and tension hang over the farewell party.

The parents and their friends can also be seen. Many of them are sceptical. They call it a waste of time; what's the point of sailing around the world?

Who knows how white sailors are received in Africa and Oceania?

On top of that, it was dangerous. It was 1973, the Cold War was raging everywhere, and at the same time more and more countries from Oceania to Africa were declaring their independence - who knows how white sailors would be received?

Inspired by Wilfried Erdmann and the Koch couple

There are only a few reports of their experiences. It was just six years ago that the Kochs, the first German couple to sail around the world, returned. And when Wilfried Erdmann docked in Heligoland five years ago after becoming the first German single-handed sailor to circumnavigate the globe, no one wanted to believe him at first. The ship was too small, his adventure too big.

The four boys have devoured the books by the Kochs and Wilfried Erdmann and have long since been infected. The doubts of the adults encourage them in their plan. What's more, Nikolaus' parents are on their side. They are sailors themselves and have taken the friends on several Baltic Sea trips.

They even provide a new boat for the big adventure. The ten-metre GRP yacht is robust and fast. At the request of father Hansen, who is a great believer in youthful vigour, the ship is named "Peter Willemoes" after an 18-year-old lieutenant in the Danish navy who attacked Admiral Nelson's flagship with a crew of 129 in the naval battle of Copenhagen in 1801.

An alternative way of life at sea

The four friends have more peaceful things in mind. In keeping with the spirit of the times, they wanted to "try out an alternative way of life" at sea. As they later write, they want to function as a "closed community in which everyone is one hundred per cent dependent on each other and at each other's mercy".

Hierarchies, what a devil of a word, should not exist on board - which presupposes that everyone "endeavours to acquire skills and abilities equally". They have put in two years of hard work, have completed the sports offshore navigation course together and have all mastered astronomical navigation.

They have transferred the ship from the shipyard in Greece to Hamburg and made it fit for the world voyage in winter storage. They have studied all the relevant international sailing manuals, and everyone can splice, sew sails, dismantle the engine and cook reasonably well. They are ready.

"Boys, keep the colours clean!" warns the man from the NRV

In the afternoon, shortly before departure, a man with gold buttons on his navy blue blazer climbs on board, a representative of the North German Regatta Association. He hands over small gifts, then points to the NRV stander in the masthead: "Boys, keep the colours clean!" A phrase that is often quoted with laughter during the voyage, especially in the South Seas.

How can the two-year adventure be financed when, as a young person with a penchant for independence, you don't really want to be given anything for free? The crew had blood taken every three days for a study by the Maritime Medical Institute, and the reward for this was medication and emergency provisions. The German Navy provided a distress radio buoy on loan in return for a receipt.

The subscription idea proved to be the most lucrative: at the end of a big lecture evening a few weeks earlier, the boys announced that they would be sending out a travel report by airmail every two months. Their offer is called a subscription for an adventure. "Anyone can pay as much as they want," they explain.

Some friends give 20 German marks, wealthy adults many hundreds. A total of 6,500 marks was raised, a huge sum, which the crew used to buy ropes and safety equipment, a sextant, a chronometer and a Windpilot self-steering system.

A stolen construction site lamp on the backstay

The ship sets sail from Wedel in a fresh wind, many people are standing on the jetty. The four of them wave briefly, then set sail. Finally they set off. The white half-tonner glides down the Elbe with new sails from Beilken, the jib with shiny brass stays, the German colours on the wind vane of the self-steering system.

The yellow paraffin lamp, which will dangle from the backstay throughout the journey, is hidden below deck. The boys took the robust lamp from a building site as a precaution, as they distrust electric navigation lights.

After two months, they reach the Canary Islands. The friends take their time, as they don't want to return to their studies and training until mid-1975. None of them had ever been overseas before.

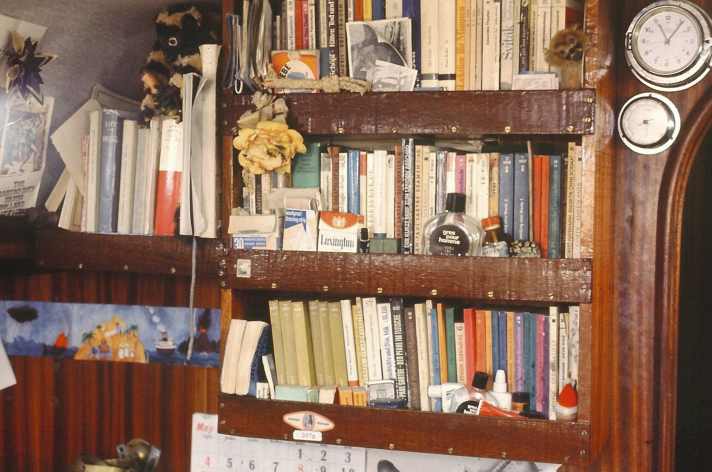

They have been able to gather little information about all the countries, islands and cities that now lie ahead of them. There is no internet, only books: old travelogues, atlases and country guides, harbour handbooks, with luck a Merian booklet about this or that destination.

Exotic worlds on the Canary Islands

They plan to spend almost half of the two years at sea. During the rest of the time, they want to explore countries and cultures. The travelogues of the "Peter Willemoes" crew will eventually comprise 105 closely printed typewritten pages. They will familiarise the subscribers of Luftpost with worlds that are completely foreign to them - and which today, 50 years later, also seem exotic: because such worlds often no longer exist, neither at sea nor on land:

"The Canary Island of Gomera is visited by fewer than 1,000 tourists a year. We anchor in the harbour of the capital San Sebastián. The harbour water is so clear that we can see the bottom everywhere and it's great fun to swim directly from the ship. We set off on excursions lasting several days on foot or by bus. We tie up our packs, take pocket knives, plasters, oil sardines, anaesthetics, string and oilskins so that we can sleep outdoors. We spend the night on beaches and are often invited for dinner. We go hunting and fishing with some of our peers. Rainer, wearing diving goggles and a harpoon, catches a twelve-kilo manta ray, which even the fishermen in the harbour marvel at."

They spend a month looking around the Canary Islands, then set off for the Caribbean. After three days, they reach the trade wind zone. The young sailors from Hamburg hoist the mainsail, hoist two trade sails on the forestay, set the self-steering system, hang the trolling line aft and indulge in the pleasure of crossing the Atlantic in the warm north-east trade winds. At last! The legendary barefoot route is reached and the actual circumnavigation begins.

Analogue navigation, no night watches at sea

There is no longer any connection to land. Near the coast, they listen to the BBC weather report twice a day, but their short-wave radio has no reception on the high seas. If a tropical cyclone were to approach, they would only be aware of it when it hit them.

In the 1970s, however, the weather phenomena at sea were much more stable, and it was possible to predict quite reliably where the trade winds would start and how far the treacherous doldrums would extend. The four have worked out their course along the barefoot route in such a way that they are highly likely to encounter good sailing weather everywhere.

GPS and chart plotters: not yet invented. They used sextants, chronometers and nautical charts to navigate. At midday, they shoot the sun twice, mark the new position on the nautical chart and use two course triangles and brass compasses to check whether they need to change course. That's all there is to daily navigation.

They have lashed the life raft to the deck, two foam life jackets to the pushpit and the distress radio buoy. The friends have drawn up a plan of action for emergencies in which they have to abandon ship; everyone has precise tasks. They don't want anyone to accuse them of recklessness.

Nevertheless, everyone goes to bed in the evening and sleeps through until sunrise. They do without night watches. The trade wind blows steadily, the wind pilot works well, and the Atlantic is empty - during the 29 days to Barbados they only see three ships on the horizon.

A large radar reflector is attached to the masthead and the storm-proof paraffin lamp shines on the backstay at night. They do not use the navigation lights as the on-board batteries are always flat because they are reluctant to start the engine, which soots up the forecastle during operation. Even when their distance travelled shrinks to 30 to 50 nautical miles during a week-long lull, they leave it off. After all, they have time:

"Our everyday life has settled down. Reading, writing a diary, writing letters, playing chess, cleaning, fishing, small repairs, dozing, dreaming, watching, listening to music. Just having time.

The two highlights of the day are the site assessment at lunchtime and our main meal in the late afternoon, where we take it in turns to cook. We try to learn Spanish. We listen intently to a tape recorder that incessantly describes living room furnishings and family relationships in Spanish.

We enjoy the sunsets together in the cockpit. Afterwards, we play Doppelkopf by the light of the paraffin lamp, often over a bottle of wine. We soon start to get bored with Doppelkopf; we know each other so well by now that we know early on what cards the others have in their hands."

In the Caribbean, they meet British celebrities and Princess Margaret

In the Caribbean, the four friends also call at the private island of Mustique, an exclusive retreat for British celebrities. When a dinghy capsizes in a storm off the island and threatens to drift away, they rescue the sailor; it is Sir Hugh Fraser, owner of the London department stores' Harrods. He invites them to an opulent dinner as a thank you. There they meet: a Broadway composer, a top London model, the singing star of the musical "Jesus Christ Superstar" - and Princess Margaret, the sister of Queen Elizabeth II.

In the Panama Canal Zone, still US territory at the time, a CIA officer tries to recruit the sailors as "assistant CIA agents"; the trip to the South Seas makes them interesting for the secret service. "If you come across yachts with drugs on board, send us a message. If you're successful, you'll get a reward."

The Galapagos Islands, recently declared a national park, can now only be visited with a special permit. The young Germans take their chances - and are allowed to stay for eight days despite their lack of papers: At the local hospital, they translate the package inserts of numerous medication donations from Germany into English. And when the bishop of the archipelago invites them to a party at the new Humboldt Grammar School, they enrich the evening with the "Hamborger Veermaster" and, at their insistence, the German national anthem.

Sartre and Camus, The Who and the Stones as a distraction

From Galapagos, the Hamburg crew will sail through the Pacific for a month. Their destination is the islands of the South Pacific. They have plenty of canned food on board, as well as 360 litres of drinking water in rubber tanks. It has a horrible aftertaste, but as tea it quenches their thirst. They cook noodles and rice in seawater.

They read a lot. Together they have compiled an extensive on-board library. A lot of thought-provoking literature by contemporary authors: Sartre, Camus, Mitscherlich, Lukács.

Reading means privacy, the chance to leave the group for a while, to mentally step outside for a few hours. They listen to the soundtrack of their generation on the tape recorder: Cat Stevens, Donovan, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, The Doors.

They sail close to the equator, it is scorching hot, and to refresh themselves, they jump overboard when there is little wind and let themselves be pulled through the water. They often sit together naked in the cockpit, their bodies a deep brown colour, their hair bleached by the salt water.

Writing the experience reports together becomes a fundamental debate about the experience

They write a lot: diaries, thoughts on the literature they read, hundreds of letters. They kept in touch with home by airmail. In the larger harbour towns, they went straight to the main post office to collect letters. Before their departure, they had sent a list of 17 place names to their friends, where the greetings were to be sent by post.

Phone calls are priceless, but the poste restante system works well - also important for Heinz, who takes photos and films on board and, thanks to the letters, finds out whether anything at all can be seen on the rolls he sent home to be developed many weeks ago.

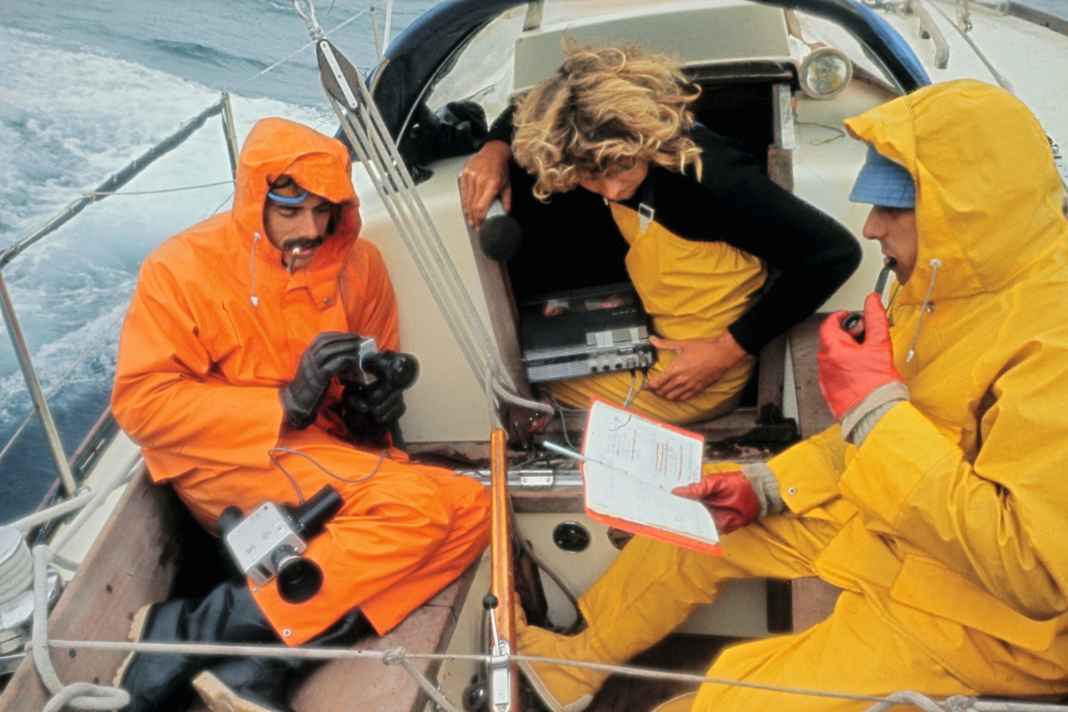

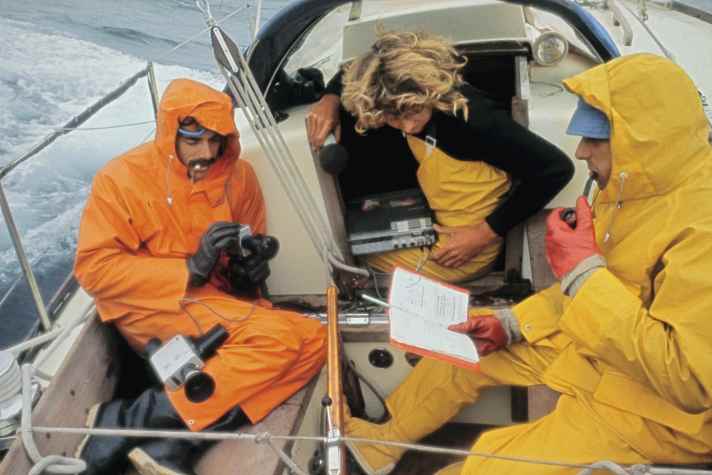

They write the reports to the almost 100 subscribers collectively, of course. They discuss each sentence endlessly, often in fundamental debates about their experiences, which also involve perception, ego and sensitivity. Heinz writes everything down and later dictates it to Nikolaus, who types the reports on a red Olivetti typewriter.

Sensual time in the South Seas

Seven months after the start of the voyage, the "Peter Willemoes" reaches the South Seas. The friends didn't fall out, nobody got cabin fever, nobody got sick, they didn't run aground anywhere, and with the help of a sextant and radio direction finder, they found every island and every harbour at the first attempt. The young men are relaxed and ready for the South Seas. They spend four months on the islands. It will be the most sensual time of their trip around the world:

"There aren't many circumnavigators in the South Seas, especially not from Germany. We quickly make contact, initially with Europeans. There's usually an expat club somewhere with pool and cold beer. We sit together and at some point we ask if there is a launderette here. A woman usually says that we can take the washing to her house. And then a chain of private invitations begins.

We spend most of our time on Tahiti and Moorea, six weeks in total. In between, friends from Hamburg visit us. Their stories at home could be the reason why all the letters we received soon afterwards were full of strange allusions to our alleged goings-on in French Polynesia, from which they concluded that the 'Peter Willemoes' had fallen into disrepair and decay."

In the Timor Sea north of Australia, they cross large shoals of tuna, with flocks of birds circling above. Sometimes the yacht passes small brown mounds, which are the shells of giant sea turtles. The sailors see metre-long sea snakes, and once a manta ray follows the yacht for hours, flapping its wings as it glides through the crystal-clear water.

Meeting with Eric and Susan Hiscock on Cocos Island

Only a few hundred people live on Cocos Island, an atoll in the vastness of the Indian Ocean, more than 2,000 kilometres from Australia. The "Peter Willemoes" reaches the atoll deep in the night. The crew carefully feel their way through the passage into the unlit lagoon, each coral head standing out against the white sandy bottom in the moonlight.

The sailors anchor in the mirror-smooth water near the atoll ring - and hear the churning ocean foaming against the shore on the other side of the island strip. There is no more sheltered place to anchor.

The next morning, an elderly couple row alongside in their dinghy and greet the Hamburgers according to English yachting etiquette: they are Eric and Susan Hiscock, probably the most famous role models of all circumnavigators.

They reach South Africa via Mauritius and Madagascar. They stay there for 61 days, their longest stay. The main reason for this is that all four of them have fallen in love. Each of them spends a lot of time with their girlfriend, without the others, and the thought arises: Why not just stay?

You definitely want to complete the journey

When they meet up in between, however, nobody seriously raises the possibility. They have been travelling together for a year and a half, most of the time in close quarters, with nothing to keep them apart - and now that is supposed to fall apart?

What's more, they are almost round the world, they want to finish and not break off prematurely. They have met enough sailors who have got stuck in harbours, and their friends see this as failure.

They set off from Cape Town at the end of January 1975, expecting to sail 70 days to Hamburg. For the first time, they had the feeling that they were on a return journey. They are caught in a heavy storm in the South Atlantic. The companionway remains closed for four days, the helmsman huddles in the cockpit, where breakers regularly come in from aft, while the others wedge themselves below deck.

The group grows together again in angry seas. Two months later, they cross north of the equator on the course they were on in 1973 on their way to the Caribbean. They have sailed around the world.

"When we leave the Azores, it gets brutally cold. Anyone sitting at the helm has to wear several jumpers, with this horribly stiff oilskin over it, you sweat yourself to death under it, and at the same time it always lets water through in several places. We're worried about the shrouds, several of them break in the strong wind. You can also tell that the sails have travelled the world; the mainsail tears twice.

We just don't fancy each other anymore."

We hardly talk to each other any more. We've agreed on 24-hour watches, always in pairs, which has the advantage that you have every other day completely free and can retreat to your warm bunk in silence. We only really talk to each other when changing watch and at lunch. It's not that we're at odds with each other. We just don't fancy each other anymore and don't want to see each other - which is difficult on a small ship."

Nobody is watching their arrival

In the German Bight, the four Hamburg sailors pass the familiar lightship Elbe 1. In the mouth of the Elbe, they hoist around 20 guest country flags up to the spreaders. But nobody is watching when they moor in Wedel harbour shortly after midnight in May 1975.

They actually made it. Once around the world, 330 days at sea and 349 on land. In their luggage are experiences that every circumnavigator has and that will stay with them for the rest of their lives. But also experiences that can no longer be made today.

Text: Andreas Wolfers