Harbour manoeuvres: Lying safely and calmly alongside in the packet

Going into the packet, i.e. mooring alongside other yachts, can be a highlight in a positive sense. Because of the short distance to each other, the mutual help with mooring, the entering of other yachts, you inevitably get closer to each other than would be the case in a box. If the chemistry is right, it can be a wonderful evening with nice people and new friends.

Another positive effect is longer sailing days. If you accept from the outset that you won't be able to find your own box in the harbour as a late summer, you can also enjoy the afternoon and early evening out at sea. This saves you having to rally into the harbour in the early afternoon.

Some sailors, on the other hand, don't like the idea of lying close together with others. For one thing, it means giving up some of your privacy and adapting your everyday life on board: Strangers walk over your own boat, the supply of electricity and water is not guaranteed, shore leave and errands become a little more time-consuming. On the other hand, mooring and casting off manoeuvres can be a little more demanding. These are all worries that make some people prefer to head for the next harbour early.

Unpleasant customs in the parcel

It also happens occasionally that sailors try to fend off other boats that want to go alongside them. In such cases, no fenders are deployed on the free side, dinghies are moored or other crews are verbally fended off. Often with the saying: "But we're leaving very early tomorrow". But in view of increasingly crowded harbours, the desire for privacy alone does not justify such dismissive behaviour; good reasons are needed. For example, if the yacht is structurally unable to take on the pressurised loads of other boats. In this case, however, it would be appropriate for the yacht itself to cast off, let the others inside and moor outside. This also applies to the alleged early mooring or in the event that a small boat is moored inside and a much larger boat wants to moor outside. You should simply swap.

If, on the other hand, you are moored on the inside and want to cast off earlier than the outsiders, you must not simply let them go. The crew should be woken up and made aware of the wish to cast off. However, if they are "playing dead" because they still want to sleep in or are even hungover in their bunks so that no contact is possible, you will have to find another solution. In this case, one of your own crew members should remain on the other person's yacht to ensure that it is well moored again after casting off. The crew member is collected again after the casting off manoeuvre and the other crew must accept the other crew members entering and handling the yacht if they themselves do not react.

Apart from good seamanship, there is also no legal means of preventing others from mooring alongside. When you enter a harbour, you are subject to the harbour regulations and these normally provide for as many yachts as possible to be accommodated, which also includes mooring alongside.

A little preparation and mutual consideration are therefore required for the parcel delivery. We show you how to do it stress-free.

This might also interest you:

How to go into the pack correctly

Harbour masters organise mooring in some harbours, in others rows of berths for different boat sizes are specified. In most cases, however, the choice is left to the skipper.

Mooring to larger yachts

The first thing to do then is not to go alongside smaller boats, but always alongside boats of the same size, or even better, slightly larger ones. Heavier boats are an enormous burden for small, inboard yachts. If in doubt, it is better to swap places and move to the outside.

Observe freeboard height

The freeboard height must also be taken into account: The rubbing strake of high-sided yachts can possibly press on the sea fence of lower boats.

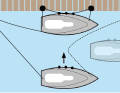

Bow to bow or bow to stern?

If you want to go into the packet, you should ask the neighbour in question for permission beforehand and have lines and fenders ready. Mooring is similar to mooring alongside the jetty. Proceed as carefully as possible. Whether boats should moor bow to bow or alternately bow to stern depends partly on the external conditions. For example the masts of two neighbouring residents are not level with each other when the boats start to roll due to swell or high winds in the harbour. Their spreaders could get caught and the rigs could be damaged. Then it is better to lie bow to stern. Or move a boat one metre forward or aft.

Advantage of alternate lying: Everyone has a little more peace and quiet in the cockpit. However, this makes the route over the foreships of the other boats longer; going ashore becomes a slalom run. In addition, the wind may blow into the cockpit and companionway of every second crew, and the waves will slap against the stern. In most cases, it will therefore be more comfortable for everyone involved if all the bows point in the same direction.

Driving against the wind

When approaching another boat, you should take care to approach against the wind if possible, just as you would when going alongside at the jetty. Especially when the wind is stronger. This considerably reduces the risk of scraping against the side of the other boat. Deployed fenders do the rest. Once they are in place, they are adjusted and the mooring lines are taken up.

The boats should be parallel to each other. Modern yachts in particular are just as wide at the stern as they are in the centre. Many crews set the fore line too close and put too much slack on the stern line. If this is done on several boats, the end result is not a stable packet, but an arc that wastes a lot of space.

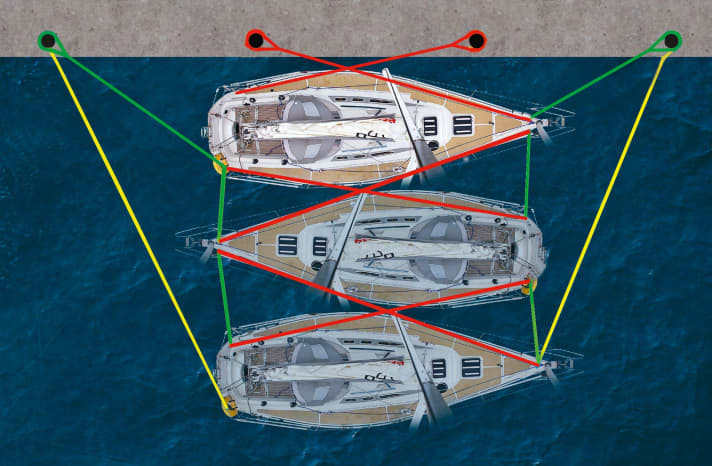

Deploy shore lines

Shore lines prevent the interconnected group of boats from moving forwards and backwards. For this to work, the lines must also be deployed at a sufficiently large angle from the outer ships to the shore. However, this is often no longer possible above a certain number of packet carriers. In such a case, lines to the boats in the neighbouring packets fulfil the same purpose.

Additionally anchor

In strong onshore winds, additional anchors can be deployed to the side by the yachts on the outside to stabilise the pack even better and relieve the pressure on the boats on the inside.

Optimum dispatch in the pack

Boats rarely come as close to each other as they do in the packet. However, this is not a problem either when mooring or casting off or after mooring. If it is clear which way round a boat wants to moor to another, all the available fenders can be deployed on the corresponding side from fore to aft - they are not needed on the other side for the time being. A crew member with a balloon fender on standby can also help to prevent scrapes, especially in strong winds or if fenders slip.

Once the boat is moored, the fenders are adjusted for the stay in the harbour. Depending on the size, number and weight of the boats, enormous forces can act on the hull of an inland vessel in a packet in onshore winds. The fenders then have to compensate for the often bulbous hull shape in relation to the straight bridge. Balloon fenders are well suited for the bow and stern, long fenders for the centre. Without previous damage, they will not burst even under particularly high wind pressure, but they can be badly deformed and therefore no longer fulfil their full purpose. In such cases, alternatively or additionally tie three individual fenders together to form a thick fender package. This also fits well in gaps or ladders on the bridge. A fender board fulfils a similar purpose. Cushion fenders are also a good addition. They remain relatively dimensionally stable even under great pressure and thus retain their protective effect.

Safely out of the parcel

Boats to port, boats to starboard and the desire to cast off - some sailors are not at all comfortable with this. Often, however, this worry is rendered superfluous by the fact that the travellers more or less all set off at the same time.

Clear agreements with the neighbours are important. It can make sense to clarify who wants to leave when on arrival. If an inside berth holder wants to leave at five in the morning, experience has shown that everyone is happy to agree that they will go outside the evening before so that the others can continue sleeping. The outside berth holder can then cast off in peace and quiet in the same way as from a jetty.

If you find yourself in the middle of the pack or as the first boat at the jetty, you should clarify with your neighbours in good time when you want to leave so that they can plan their day. In tidal areas, the tides and the destination determine the time of departure, so there is not much room for manoeuvre for those leaving.

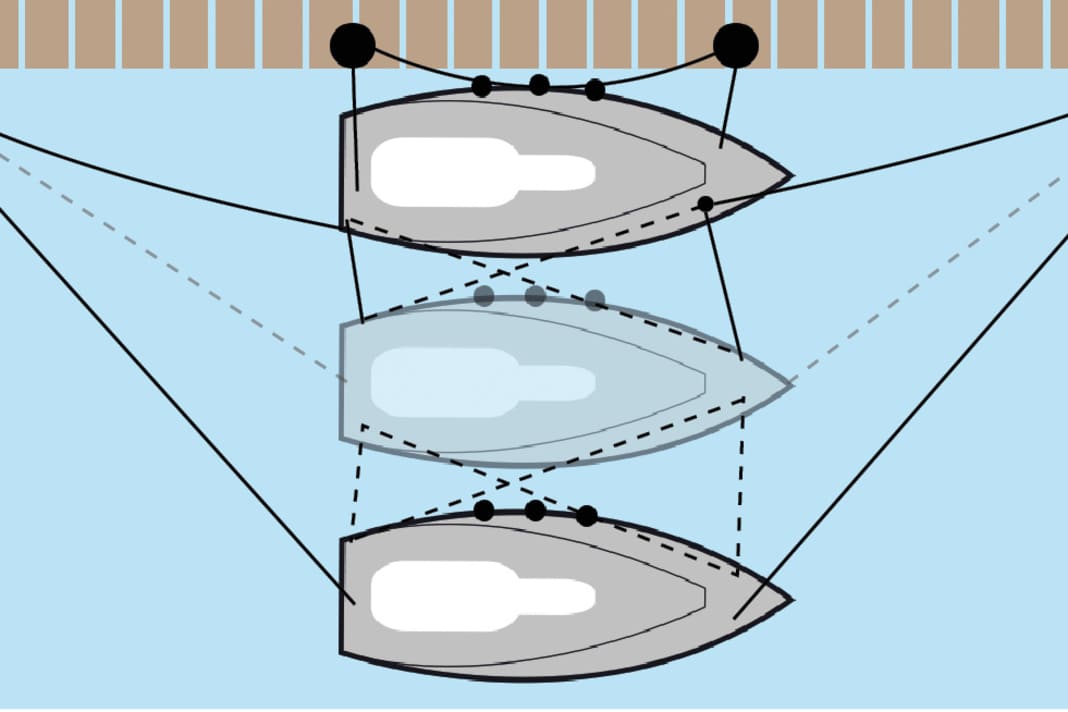

Not all boats always have to leave when an inboard berth wants to leave. If there is enough space in front of or behind the packet, the boat can leave without much effort. The sequence of images shows how this works. Initially, action is only required on the directly neighbouring boats. Several boats can be easily moved from there with line work, if necessary by tightening the lines via the winch or with the help of several people.

Exit with leash aid

Unless there is a lull or little wind, you should always sail with the wind, not against it. This is the only way to ensure that the remaining yachts are not pushed away by the wind and drift away uncontrollably. However, caution is advised with such manoeuvres with large boats. They drift quickly and you can't hold on to the line with your hands. The line must always be placed around the cleat.

In strong offshore winds or if there is not enough space, it can therefore also make sense for the outer boats to cast off briefly.

If, despite good consultation, everyone is ready for the manoeuvre and only one crew is on an extended shore leave or still slumbering, the departure does not have to be delayed. It is an absolute no-go to simply cast off the lines of other boats and sail off. And unnecessarily so. There are almost always helpful sailors on neighbouring boats or on the jetty who will help you cast off with line work. If necessary, a member of your own crew can also be placed on the neighbouring boat or on the jetty and collected again later.

Even brief mooring and unmooring under motor can be achieved with an unmanned boat towing alongside - provided you are careful and experienced. It is always helpful to have a few helping hands on the jetty or on the boat to which the boat is to be moored again, as well as clear instructions to everyone involved.

Small parcel etiquette

Tightness quickly leads to friction. But you can avoid trouble with a few simple rules:

- Outside berths hang out fenders and keep the side and cleats clear. Fold in the sun panels on the railing

- Ankommer ask for permission to moor. Permission will only be refused for good cause

- Accept lines and adjust your own fenders

- Only enter other people's boats via the side and the foredeck, as quietly and as rarely as possible. Instead of individual trips ashore, for example, combine a trip to the wash house and to the rubbish bin

- Wear clean, board-compatible shoes or walk barefoot when stepping over (caution: risk of injury!). Hiking or walking shoes are only put on at the jetty

- When stepping from the jetty onto the boat, do not pull on the sea fence, but hold on to the shrouds

- Inside berths tidy up the foredeck. Spibooms, washing lines or bicycles make passage difficult for neighbours

- Keep noise to a minimum in everyday life on board, such as music, loud conversations, the whirring of a wind generator or the engine to charge the batteries

- Do not run the power cable over the deck of the inboard berth, but around the outside, for example over the anchor

- If there is a shortage of sockets on the jetty, you can let neighbours use an extension cable. But then do not operate any particularly powerful consumers

- Make clear agreements regarding the planned departure and then stick to them