When the whirring of the crane sounds through Strand harbour, looking in its direction is a natural reflex for many sailors. This morning, they take a particularly long look. The elegant, narrow hull of a classic boat begins to float and shows off its elongated lateral plan. And yet the negative stern, the moderate jump and the slight edge in the stem make it look somehow modern compared to the well-known wooden boats of the Lang & Schlank brand. The boat hangs in the crane like a feather and is guided by the lines with a light hand until it is lowered into the water with the bright whirring of the fast gait. There it floats up high and dances gently as the owners climb on board to haul off the hot gear.

Uwe Baykowski and his wife are clearly delighted with what they have done. For four years, Baykowski worked on the 5.5 "Sünnschien" with the help of his wife and their two daughters, whenever his job and the sailing on their family boat gave him time. For the master boat builder and expert - specialising in classic boat and shipbuilding - making full use of all the opportunities offered by the craft was both a challenge and a pleasure. What he and his family have saved as a result is nothing less than the most successful German Olympic boat in its class.

Sheer deck, shiny wood

It's early in the morning when the two of them are hauling their Low German Sonnenschein under the mast crane. A short time later, the aluminium profile from the manufacturer Proctor, which dates back to 1967, is in the foot and the shrouds and stays are attached. The boat is almost ready for sea.

The eponymous natural phenomenon is not a matter of course in northern Germany, but today it has materialised. The gunwales made of mahogany lacquered by master craftsmen gleam, the slightly greying stick deck made of selected Burma teak almost glows, and the precision with which it was laid really comes into its own in the sunlight.

Now the love for the boat should grow"

The deck is uncluttered, almost "sheer" in the jargon of the boat's name. The eye doesn't get caught by mooring cleats or traveller or genoa rails. The numerous sheets, halyards, haulers and stretchers all disappear somewhere inconspicuously below deck, where they are hidden from view. Nevertheless, it takes a long time to fully appreciate the beauty of this gem. The aesthetics of the shapes, the balance of the dimensions and the flawlessness of the surfaces really lull the viewer. "Now the love for the boat should grow," says Baykowski and laughs.

The Olympic boat fuels the passion for 5.5s

When he brought the small racing boat on a trailer from Holland five years ago and drove it to the Strander shipyard, it was not clear whether everyone involved in the project would really be able to fall in love with it. But it had all happened very quickly for Baykowski too. When the guardian of the class association, his friend Kaspar Stubenrauch, rediscovered the prominent boat that had disappeared from view after some research in Holland, he put a flea in the ear of Baykowski, who had been latently addicted to 5.5s since his apprenticeship in Schleswig. "There's the 'Sünnschien', the old Olympic boat, you have to get it!" The enthusiast doesn't think twice and heads there, "without anyone knowing about it. I barely looked at the boat and bought it. Suddenly I was standing here in Strande with it. That didn't go down well."

But the master has made a mistake. The boat's Olympic past contributed to this. "My teacher Hans Baars-Lindner lived in Switzerland after the war and grew into the 5.5 scene there. He sailed in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Naples on Herbert Scholl's G 7 'Bronia'," recalls Baykowski, who has felt magically attracted to the construction class ever since these stories.

5.5er as a favourable, light boat class

This was created in the barren post-war years. When an international arena for sailing was to be created again after the Second World War, one of the tasks was to find a replacement for the 6 metre yachts. For half a century, the underlying metre formula, according to which the boats are designed and measured, has dominated Olympic sailing. However, the comparatively high purchase prices for new builds in this class are no longer in keeping with the times. The formula results in heavy boats, which leads to high costs for the stable construction, the expensive lead ballast and the correspondingly generously dimensioned sail wardrobe.

The British designer and metre-class specialist Charles E. Nicholson took up the cause and modified the International Rule - he had already played a key role in its development 40 years earlier - without further ado for this project. The result is the 5.5 ( see below ). The new boat remains a construction class, but weighs only around half as much as the six and therefore requires half as much lead and sailcloth.

'Sünnschien', the Olympic boat, you have to get it!"

Nicholson builds the first boat, the K 1 "The Deb" in 1948/49. The IYRU recognises the class as an "International Rating Class" in 1949. The 5.5 made its Olympic debut three years later at the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was not until 20 years later, at the 1972 Games in Kiel, that it was replaced by the open keelboats Soling and Tempest.

But the loss of Olympic honours is by no means the end. On the contrary, the class is destined for a second life. For one simple reason: the dimensions of 5.5s - the boats are around 9.50 metres long, weigh 1.7 to 2 tonnes and have a sail area of just under 30 square metres on the wind - make them just as easy to sail as kites or lacustre. At the same time, however, they still regularly tempt designers and clients to build new boats because the rules are very open to change.

5.5s are a mirror of the development of sailing

In the seventies, the first boats moulded using the vacuum process appeared. GRP is authorised at the beginning of the eighties. Self-draining cockpits are designed early on, and keel and rudder moulds reflect the current state of yacht development. Today, carbon rigs are just as common as ingenious trim tabs behind the keel of modern boats with a split lateral plan.

Simply put, the 5.5s also combine the best of both worlds when it comes to sailing. They are ready to go after work in a matter of minutes. The owner can also upgrade his boat and sail as ambitiously against high-calibre competition as if it were winning the America's Cup.

Following their retirement from the Olympics, many former competitive sailors are therefore drawn to the class, precisely because they no longer want to compete in the Olympics, but still want to be active at a comparable level. It is not only this competitive situation that makes sailing a 5.5 challenging; the boat handling is also more for advanced sailors. The spinnaker is large and there are hardly any winches on board. Travellers for the mainsail are no longer available on boats with a new type of boom vang.

"Classic", "Evolution" and "Modern"

The international class association counts more than 700 boats in over 30 countries. The German fleet has been experiencing a renaissance since the 1990s and is now the largest in the world with 80 5.5s. There are also several local fleets in this country. The youngest was founded in Kiel in November 2013, where the first German boat, G1 "Tom Kyle" by Dr Hans Lubinus, was based back in 1952 and sailed to the Olympics off Helsinki that summer.

The fleet is divided into three age categories. Classic wooden long-keelers - such as "Sünnschien" - are labelled "Classic". The design years 1970 to 1993 form the group called "Evolution", and more recent boats are "Modern". No other active keelboat class has developed so much since the beginning. Despite all the differences, the 5.5s start and sail together, and prizes are awarded for Evolution and Classic. This makes the class unique worldwide.

"Sünnschien" started as a Canadian with a US sail number

"Sünnschien" was built in 1967 in Burlington on Canada's west coast, at the Ontario Yachts shipyard owned by Dutch expat Dirk Kneulman; today she is a typical representative of the late classics. Kneulman had only been in the business for six years when he built the boat and yet he had already made a name for himself internationally. Nine of the 14 5.5s taking part in the Summer Olympics in Mexico the following year came from his slipway. The new addition to the overseas fleet with the sail number USA 72 was commissioned by the American Gordon Lindemann. He commissioned Britton Chance Jr. as the designer and named the boat "Cloud 9". Together with Gordy Bowers and Buddy Melges, he sailed the new boat to first place in the 1967 World Championship and then sold it to the Hamburg sailor Rudolf Harmstorf.

Harmstorf christened the boat "Sünnschien" after his wife's pet name and sailed to a respectable fifth place in a field of 48 competitors at the European Championships in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on Lake Neuchâtel in 1968 and only just missed out on a bronze medal at the Olympic Games in Acapulco, Mexico, in the same season, finishing fourth. The exact circumstances of the qualification are not known, but there was no elimination on the water, although there were two competitors. According to YACHT, issue 9 of the year, Harmstorf was "nominated" by the DSV Olympic Committee.

"Sünnschien" without much competition

The effort involved in taking part in such regattas is enormous. The boat has to be transported to the venue by train or cargo ship, which puts the comparatively low acquisition costs into perspective. Sailing internationally is still only possible for a small clientele.

A photo album and newspaper articles from Harmstorf's estate provide an insight into the 1968 season and the 45-year-old's participation in the Olympics. At least the reporters of the relevant daily newspapers were not surprised that no competitions were necessary: "There are no German title fights in his class. Because there are only 18 boats in the whole of Germany. And most of them are not ready to race. Well, with acquisition costs of 30,000 to 40,000 marks ..." Even in the days of the economic miracle, these are astonishing sums, corresponding to a current value of around 80,000 euros.

For Harmstorf, this kind of investment in his passion does not mean ruin. He is internationally active with a hydraulic engineering company and has emerged as the developer of the vibro-injection process for cables and pipes. He has built up a lucrative business with it.

New start for the "Sünnschien" Cup

After two seasons, Rudolf Harmstorf sells the boat to Karl Heinz Sauer, who takes it to the start of the 1972 World Championships on Lake Geneva and finishes 20th. Then it was quiet around the German boat that is still the most successfully sailed Olympic boat in its class today. In the mid-seventies, G 17 goes to Lake Constance as "Ambition", is then sold to Holland as "Lorbas", where it is finally called "Zonneschijn", tracked down by Stubenrauch and brought to Strande by Baykowski.

"That was in 2015," recalls the master boat builder and explains that he had great ambitions to jump straight into the regatta action - and he did. "We travelled to Niendorf and sailed in the Sünnschien Cup, named after this boat," says Baykowski. The prize was donated by the class association in memory of the Olympic past of this very boat, after previous owner Harmstorf, who had taken a lively interest in the recent flourishing of the class, had made a generous donation. "Then we travelled to Copenhagen and sailed in the Wessel & Vet Cup," says Baykowski, "in really strong winds. And everything held up!"

Four years of restoration work

Motivated by this, he gets down to the winter work. Baykowski explains that he just wanted to make everything "a bit smart". But when he began to work more intensively on his new acquisition, it soon became clear that a major restoration would be necessary. While the double diagonally carvelled mahogany hull is still completely intact, there are problems with the deck structure: "I realised how rotten it all was."

I actually just wanted to make them a bit fancy ..."

Baykowski works after work for four winters to restore the "Sünnschien" to its former glory. He removes the deck and repairs the beams. While his daughters sand and paint the inside of the entire hull, new deck beams and a plywood deck are created on which the master boat builder lays the teak poles.

"I never did anything in the summer," says Baykowski, who then sails 37 Wednesday regattas and multi-week summer trips to the far north with his wife on the self-built Luffe - their daughters have long been travelling on their own keels. And even in winter, his two jobs - he was still head of the shipyard of the Kiel Yacht Club in Strande and also worked as a surveyor - competed with the restoration project. But at some point, despite everything, it is completed.

High-tech meets historical substance

Painting the outer skin heralds the final part of the work. Together with his wife, he manages it almost perfectly. Then the almost uncountable tasks begin with the configuration of the new deck's fittings, which are brought up to the standard of today's possible solutions. "It's all high-tech now," assures Baykowski as he presents the ship after it has been rigged. Fittings were made in carbon fibre according to his ideas, and these ideas matured in hours of exchange with the experienced 5.5 sailors of Flotte Kiel and outfitters such as Peter Kohlhoff and sailmaker Uli Münker. The result works excellently, as can be seen when Baykowski and his wife set sail with well-rehearsed hand movements and set course for the open sea.

Not only is the sun shining outside, but the wind is blowing strongly from the north-west. As soon as she is out of land protection, the light long-keeler sets off, sails agilely and constantly challenges the crew with its numerous trim options to get the best out of her - a thoroughbred regatta boat, created to win at world-class level; an impression that the most successful German Olympic boat in its class radiates again today as it did on the first day.

And the future plans? Participation in the next Sünnschien Cup is a matter of honour. But there is also a very special regatta for classic 5.5s, sponsored by "Biwi" Reich, who sailed his G 12 "Subbnboana" to the Olympic Games in Enoshima in 1964. Boats that still comply with the construction regulations of that year compete for this prize every two years at different locations. "We would certainly be competitive there," says Baykowski, looking into the sail with a smile, the radiance of which honours the boat's name.

Technical data G17 "Sünnschien"

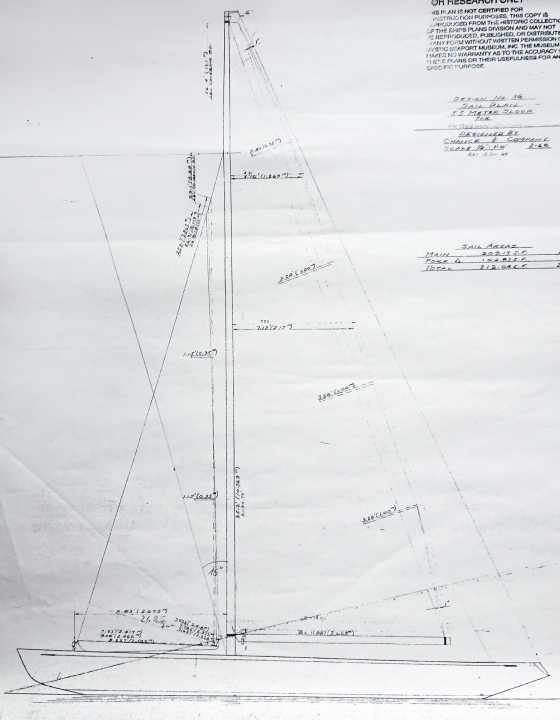

- Designer: Britton Chance jr.

- Building yard: Ontario Yachts, Oakville

- Hull material:Mahogany

- Year of construction: 1967

- Length over everything: 9,40 m

- Width: 1,90 m

- Depth: 1,35 m

- Weight: 2,05 t

- sail area: 28,8 m2

5.5: Boat with a history

The design formula for the 5.5 was conceived after the Second World War for Olympic sailing - by none other than the British star designer Charles E. Nicholson, who had already been involved in the development of the international metre formula before the First World War. The "Sünnschien" represents the state of development of the class in the second half of the 1960s, when it was still built with a long keel and made of wood. She sailed ahead for two summers, first with an American, then with a West German sail number. Today, the "Sünnschien Cup" is a reminder of this glorious era - and not least the completely refurbished boat itself, which the owners want to take back to the regatta circuit in the future

- Further information at 5point5.de

More on the subject of "classics":

Lasse Johannsen

Deputy Editor in Chief YACHT