At the start, the wind is blowing lightly from the north to north-east. Just the right weather for my departure. This gives me time to collect myself and sort out the things lying around in the cabin. All my worries are far away, simply dropped away. I put on a fresh blouse and pour myself a glass of red wine from the Canary Islands. I experience a feeling of pride. Now we really will be alone at sea for the next few weeks. "Ultima Ratio" seems like a living being to me, and I promise not to annoy her. I can't get a quote from Joseph Conrad out of my head:

A ship is not a slave. You must never forget that you owe it the fullest share of your thoughts, your skills and your self-love."

However, the sun, wind, the brightness during the day and the constant rowing soon weaken Ingeborg. She is already dead tired by sunset. Her strength is sapped far too quickly. She wants and needs to bring a certain balance into her life. She wants to make a fast crossing - a trimaran - but not at the expense of safety. To do this, she needs to be at her best. At the beginning, she resolves to take good care of her health, above all to eat regularly and to cook every day if possible. In other words, to bring a certain balance into her life for a longer period of time. She is not yet too worried about a possible lack of sleep. But that is exactly what happens, because the nights will remain restless near the Canary Islands, as Ingeborg has to keep an eye on the cargo traffic. All the shipping routes there run from north to south and vice versa.

In the morning, I'm pretty exhausted after nights of sitting and standing. I'm still not used to being on deck all night. I also doze repeatedly in the cockpit on the narrow bench seat or on the bare floor in the cabin so that I'm always ready to go. Ready to trim the sails, change course or tug at the sheets. Sleep must not be deep. Despite my marvellous lantern in the rig, I am very restless with the ship's traffic. 40 years of shore life can't just be discarded like that.

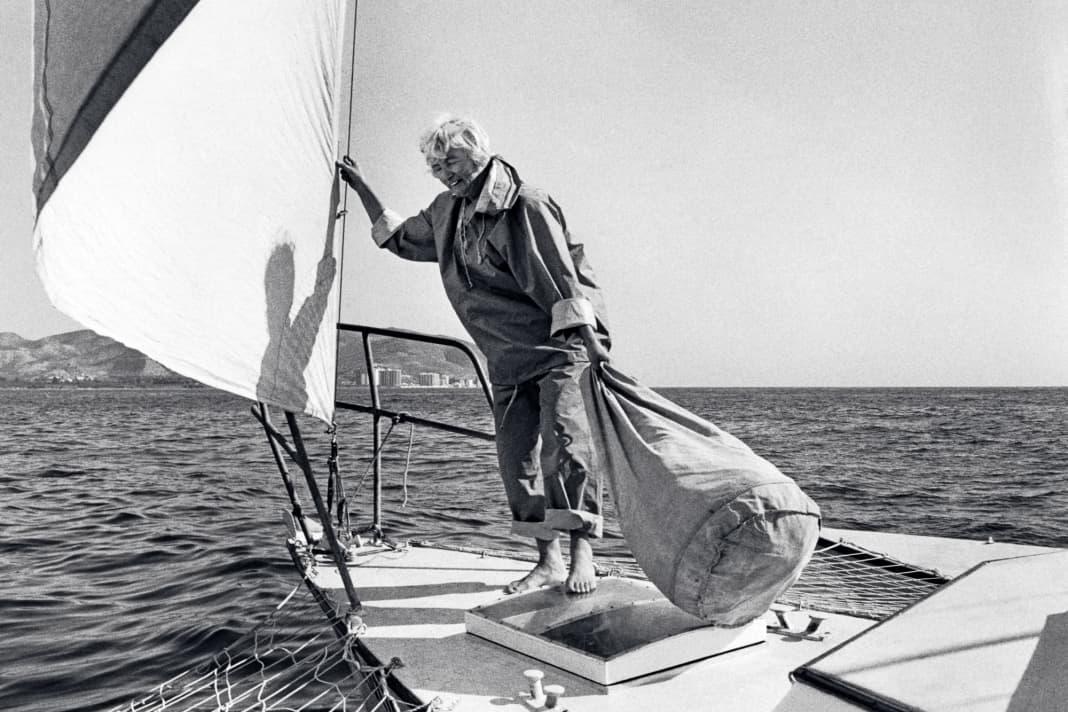

Ingeborg doesn't write that the traffic scares her either. At dawn, she usually sets all the sails again. Jib first, main is still standing, mizzen is up with three handles. Back at the helm, she operates the sheets from there, pulling them tight with the winch because the wind is halfway up. All without breakfast, the time for that will come a few hours later. When there is a calm, she has time for that and for her body. She even starts washing away the last of the Las Palmas dirt on deck with a scrubbing brush.

On the eastern horizon I briefly see a sail, it could be the two Berlin doctors with the "Lotus". They left Las Palmas shortly after me. And they're travelling surprisingly far to the east. I'm guessing they won't get over there any quicker, their boat is hardly bigger than "Kathena". I, on the other hand, keep close to the coast of Gran Canaria and turn west at the southern end.

I have to get out of the habit of comparing boat size and speed. I'm at sea and I'm happy. That should be my attitude - and remain so. I want a fast crossing, and that's why I immediately grabbed the trimaran. The boat show in London comes to mind, an hour of viewing, a Guinness, and the order was signed. Rubbish. But as a businesswoman, that's what you do with a quick yes or no.

Thick walls of cloud are gathering in the east and south. In between, the sky is incredibly blue. I'm nervous and hope that the weather won't be too bad. You always have a dull feeling before the first strong wind. You have to settle in again first.

I can't even manage a midday width today, I'm suddenly so fidgety. Either the sextant is broken or I'm too stupid. I have to pull myself together. What's going on? It's not that bad just because everything is pitch black in the sky and it's getting dark. - I've made practically no progress today.

Calm before the storm. She has time: lashing down the sails, distributing ribbons, stowing things away safely. Cooking and eating. The latter even relaxed at the helm. Later, when everything is completely dark, she hangs a second lantern on the stern. Either way, the lighting does not comply with the regulations, but it is certainly much more visible than the inappropriate position lanterns, which are usually mounted far too low on the pulpit of yachts, including the "Ultima" and "Kathena".

22 November

Set full sail in a shrieking wind. A heavy squall of rain comes through at midday, followed by continuous rain. So out on deck. Be brave, I say, and put on a south-westerly. It's the start that counts. Getting away is the most important thing.

Getting away from the country. I can still see the Pico del Teide on Tenerife to the north. It's 3,300 metres high and is, I estimate, 40 miles away. You wouldn't believe it. I bring "Ultima" to self-steer the next day and steer a compass course of 220 degrees. The wind varies between one and three Beaufort. In the evening, I put out both lights again, this time distributing them so that they are visible from all sides.

A cross with the weather. It's dreadful. In the morning, at midday, in the evening. I shoot the sun in the morning and at midday when it clears up briefly. This gives me the values for two contour lines. The result is satisfactory. That makes me particularly happy.

The times and miles will be compared. Today. Tomorrow. Next year.

25 November

Course 180 degrees. That's south and close to the wind. Where will that get me? It's raining cats and dogs. No wind in between. The sails are flapping back and forth. I have to recover them. The boat rocks, which rarely happens.

At some point, the rain stops and the wind picks up. I shuttle quickly between the foredeck and the cockpit. Tearing at the halyards, tugging at the sheets. The course is almost westerly for the first time. That makes me happy. There are no worries, no nothing. Everything floats, just because of a quarter of an hour of wind. We sail on course and make no compromises. Everything is suddenly beautiful. The sea glistens in the sun.

I change my cloths several times during the course of the day. Gusts keep me moving. But the problem with sailing alone is that you are your own opponent. Nevertheless, I love it. Does that make you lonely? No. God is with me. That's enough.

In the saloon, Ingeborg uses a panel to build a large chart table on the port bunk, big enough to completely unfold the English admiralty charts. Everything is now ready to hand there: Compasses, pencils, eraser, logbook, nautical charts. To be on the safe side, she still secures the sextant with a thin rope. Everything stays in place because the tri hardly moves. She feels like she's on the bridge of a steamer. A table can't be big enough for navigation, she thinks. Of course, she is on deck every ten minutes throughout the night. She soon gets the hang of it. One look round and a second behind the sail. And she's back on deck. Meanwhile, "Ultima" is calmly sailing her course, even under genoa only. There is little wind during the day with a cloud cover that is not uniformly grey, but strongly structured. Despite the small waves, the sea reflects the gloom of the sky. A great loneliness lies over everything. Day follows day.

26 November

2 o'clock at night. Wind three to four Beaufort from the south-west. Total darkness all around. I set the jib. She steers the ship alone. I tie the genoa to the railing, unfortunately for me not well enough, but I only realise this when it gets light. Damn, damn. I curse loudly because the genoa has worked its way loose through the overcoming seas and slipped overboard, dragging the sheet, which then gets caught in the engine's propeller. Oh dear! My heart stops for a moment. It's impossible to cut the good sheet, it would still be in the propeller. Well, that's not possible.

The sea is still choppy. There's no point reproaching yourself now, there'll be time for that later. The wind could pick up and make the whole operation even more difficult. But there's no way I can jump into the water and dive down to untie the sheet. Now that the sails are on deck, "Ultima" is lurching heavily.

The wind has picked up to four to five. But where is this sea coming from? The whole situation is pretty muddled, and ultimately the only thing to do is to launch the dinghy. I release the mooring ropes that hold it on the port side over the net. It weighs 40 kilograms. It is secured three times in the water. It is necessary to bring it between the hulls from aft, so I work upside down under water for more than half an hour with breaks to catch my breath. The sheet has twisted around the propeller about ten times. I try again and again, gritting my teeth, because the hull around the propeller is already full of barnacles that are tearing my hands and arms open.

Finally, the last sling is untied and I'm on board like a flash so that I can fish the genoa completely out of the water. Of course I'm soaking wet and totally exhausted. My arms look terrible. I've been warned that wounds heal badly at sea. A few tears roll down my face from exhaustion. There is no one to comfort me and understand my satisfaction.

Actually, I didn't deserve to enjoy a bottle of beer, because I alone am to blame for this negligence and the dangerous, strenuous work involved.

Ingeborg also realises that some of the sliders on the mainsail have come loose. Yarn and needle are quickly ready, but the mainsail has to be dropped and then set again. She spends more time on deck and is not surprised to see two freighters heading north-south. At this time of year, she has been battling bad weather and scary, thick clouds for days, alternating with tropical downpours and calm winds.

I sit down on the forecastle with a bottle and vigorously urge myself to pay more attention in the future. Triple and not just double-checking must be my motto when I do anything nautical. I'm totally depressed. If I drown, I at least want to look decent. I've dyed my hair and put cream on my face. It's always worked as a mood booster.

Fortunately, the cloud cover breaks slightly at some point in this mood, so that it is enough to shoot the sun. Now the brave woman at least knows where she is. She makes a note:

The result of the first week at sea is almost catastrophic, only 350 nautical miles in the right direction. The wind is simply not playing ball. It's still blowing from the south-west, sometimes too weak, sometimes too strong.

I don't want to go to South America - I want to go to the Caribbean.

The solo skipper, overcome by new doubts, revolts and makes additional notes:

In addition to the nautical facts, I need to write down more feelings in the logbook. Got one right away: Women are weak creatures and, compared to men, too much a victim of their changing, fluctuating feelings, which are characterised by external influences. And this is the problem with this kind of endeavour. Physically it's an effort to get through, psychologically it's a problem - at least for me.

After a week, the Atlantic sailor slowly begins to settle in better. Rotten fruit goes overboard. And the large cooking pot is put on the heat for a spaghetti Bolognese. She now wants to treat herself to this more often. She also discovers that reading a crime thriller helps to calm her nerves. She strictly follows her daughter's instructions:"WhenNothing works, just read regularly. You've packed enough books."

28 November

It's blowing from the north-east! And with a marvellous three to four Beaufort. I'm electrified. The course is 230 degrees. Finally spot on. Now it's time for self-steering. I experiment with two unfurled headsails with the sheets going to the rudder. Only when I cross the sheets does it work. Hooray, the two yellow headsails, specially sewn for me by Beilken, are working. I can sit next to them and twiddle my thumbs. A trimaran on autopilot in 1969, hard to believe. I speed into the darkness at eight and nine knots. No traffic lights, no police, no honking cars. Only water far and wide. I am free! Proud to have plucked up the courage to cast off.

Soon the Southern Cross should be visible. I can't sleep with excitement, sitting outside in the cockpit, mesmerised and watching the world around me.

No more feeling of loneliness. On the contrary, everything is wonderful. Confidence returns on board, downright euphoria. It gets even better. I sail myself into a frenzy in the Passat - thrilled by the speed of the tri, and without having to take the cloth away.

30 November - 11th sea day

That can't be right. Have I messed up the solar observation? I do another one. Do the maths, check. No doubt about it. From yesterday to today, I've clocked up 220 times. Kids, I'm catching up. If this keeps up, I'll be there in ten days. However, it's not important when I get there, just that I get there. Have Astrid and Wilfried caught up with me yet? Their boat, steel and 8.90 metres, isn't particularly fast either. I take up the chase with spray and foam!

At times, "Ultima" rushes over the three and four metre high waves with frightening speed. Lifted, carried and pushed along, it often starts to glide. The whole ship vibrates as if under a powerful engine. She hopes it doesn't hit her in the eye. The two headsails, which she calls twins, are the same size, have a combined area of 26 square metres and cannot be reefed.

The sea is extremely rough and tosses the tri back and forth. But it always catches itself again and runs its course. Later, the wind shifts a little to the east, but remains at force seven to eight. It is Ingeborg's first exhilarating experience in a trade wind. Even though surfing can be hellishly dangerous: Anyone who has experienced it once will want to do it again and again.

Ingeborg no longer flinches when something cracks somewhere on board. Her life is reduced to two yellow foresails, which are set on starboard and port on two forestays and rigged with sturdy wooden booms.

Somehow it's scary for me. I make an almost spectacular journey. The whole ship shakes and hums from time to time. I hope it doesn't hit me in the eye when it suddenly goes out of control.

It's a very restless night. I'm in the cockpit, making myself a glass of lemon juice with a raw egg. Tired? No, I'm not tired - just excited. As choppy as the sea. But "Ultima" stays on course.

I will never forget this night. Everything in me is activated. White crests as far as the eye can see. I am afraid. The speed in the boat, the high seas breaking in the wake and this terrible darkness.

I'm a light person. Now in the tropics, 12 hours of darkness in a row. I long for the first light of dawn. I will thank the gods if everything on board remains intact.

It remains. And another day passes. She makes a note in the logbook on 1 December:

Simply sensational, my navigation result. An Etmal of 270 nautical miles. An average of 10.9 knots. That almost equalled "Pen Duick", the tri by Éric Tabarly. And that with my good plywood hulls and blown-out sails.

The flying fish that I pick up on deck in the morning go into the pan. The patties add variety to my monotony. With a beer. I can feel my spirits returning. You have to treat yourself to something.

Really 270 miles! Sailing gives me the feeling of being alive.

My mother-in-law grabs the camera and certainly takes wonderful pictures of the day. Sometimes from the bow, sometimes from aft, sometimes she crawls up somewhere. Then lying on her stomach again, holding the camera far outboard. Then the sails and the sky. The seas astern, the foam flies. But - she doesn't get any of it on film. She hasn't put any in. She swears worse than ever before. The only thing that helps is food. She takes the second half of the pre-cooked steak out of the fridge, accompanied by tinned steamed artichokes. Meat still in the fridge after so many days? Yes, it works and cools very well. A glass of sherry before dinner and a pudding afterwards. Living only on tinned food at sea was not her thing.

It doesn't even occur to me that the wind won't continue like this. I finally have the trade wind I deserve. The water. The air. My boat. I did a big wash in the morning and now everything is flapping in the wind - in the trade wind!

I don't want to be frivolous, so I used sea water for the first and second rinse and only three litres of fresh water at the end. Of course, I wash dishes with salt water - just as the water for my body wash comes from this infinity. Unfortunately, everything sticks a little.

I'm starting to feel a slight aversion to the constant sea water, and my skin is burnt and sensitive. How on earth did Wilfried do it? 130 days at sea and only 60 litres in the tank. He has to explain that to me.

Five days later, disillusionment sets in. Ingeborg shoots the sun four times and almost calculates herself to death. The results are strange. Only after much effort does she find the errors. They are caused by the complicated calculations of the Semiversus formula, which she uses to navigate, but also by her exhaustion. She only manages to get "Ultima" to steer itself a few times. In the long sessions at the wheel, she turns to books. She can read while holding her course.

3 December

I proudly wander around the deck, I won't arrive in ten days, no, in seven to eight days. I will leave everyone else far behind me. My heart leaps for joy. I have breakfast in the sun.

Dreams are wonderful, but what happens the next day? Only 100 miles. Pride comes before a fall. I've got the salad. What use is the best wind chart in the world, on which the prevailing wind for this month is north-easterly? What does the present offer me? South with a course of 270 to 300 degrees in choppy seas. And quite high. From time to time it breezes up to six, seven and eight, even if only briefly.

The wind has to shift and become stable. I simply have to force it, or not. It's also pouring from the sky, as if the wetness will never stop. Black all round. The poor "Ultima" is working hard in the lakes. At 5 p.m. the weather is like in Germany, all grey in grey, cold and rain, rain, rain. In this darkness, I have the feeling that I'm ramming into something. Aren't there unlit sailing boats? After all, 20 or more boats have set off from the Canary Islands alone. As a precaution, I set my monstrosity of an anchor lantern, because not everyone else at sea is paying attention.

For the rest of the journey, I build myself a mattress camp on the floor. I need my 20 to 25 minutes of sleep, and it comes quicker in a proper 'bed'.

Today I only had a brief opportunity to shoot the sun. The twins are standing with falling air pressure and light winds. The sea, on the other hand, is choppy. I've now been at sea for 14 days, with only six days of sunshine, otherwise strong winds, clouds and rain. As dusk falls, another bank of black clouds rolls in and I get scared.

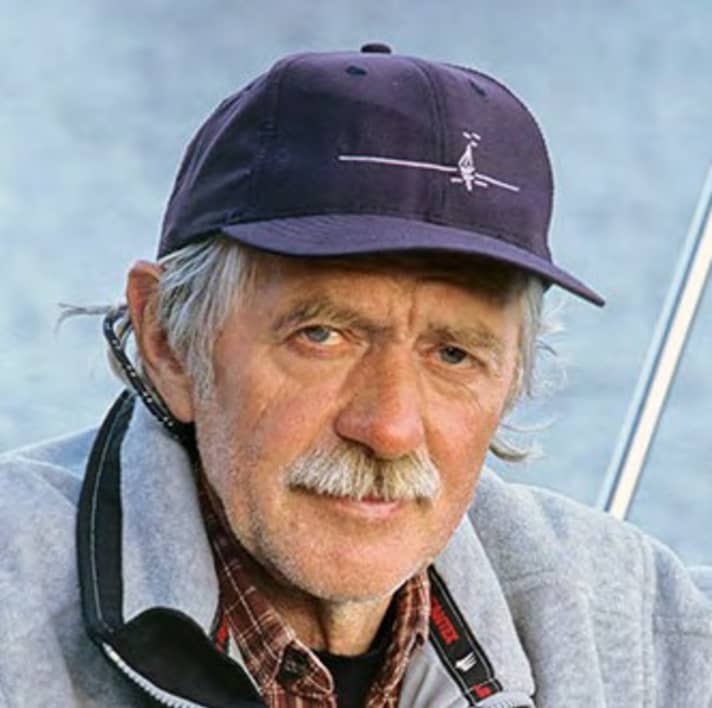

Wilfried Erdmann,

Born in 1940, he met his future mother-in-law Ingeborg von Heister and her daughter Astrid in Alicante in 1967, shortly before he left the city on his first "Kathena", a voyage from which he returned in 1968 as the first German single-handed circumnavigator. After the wedding, the couple set off at the same time as von Heister, she on the Atlantic tour described in the book, the Erdmanns on their honeymoon around the world. Wilfried Erdmann recorded the impressions he gathered on his travels in numerous books - as many other, sometimes spectacular journeys followed. The biographical travelogue "Ingeborg and the Sea" is his last book.