Essay: Sailing on Facebook, Insta and Co. The death of classic sailing literature?

Marc Bielefeld

· 10.02.2023

Silence is golden? Noble restraint the measure of all things? No way! When it comes to biographical self-presentation today, people are reaching for the full and exhausting the keyboard of modern self-presentation down to the last pixel.

This now applies to pretty much every situation in life. From the loud positioning of your career to the full presentation of your leisure activities. From tattoos, which are posted as soon as they're done, to the latest cat video. And it certainly doesn't stop there: sailing. Today's man has become a publicist of his own existence - even if it takes place on the water and the motives are basically of a purely recreational nature.

Today's record-breaking sailors beam their exciting journeys live on the Internet, watched by an audience of millions

The social media channels are churning out everything the filters can handle. Snapshot alerts are everywhere, while the ancient art of keeping a travel diary has turned into digital navel-gazing in an endless loop. If you enter the hashtag "Sailing" on Instagram alone, you are presented with 11.8 million results. Ships of all sizes can be marvelled at there, sailing beauties on all seven seas. Dreams and dreams are rubbed under our eyes, including bathing beauties lolling on the foredeck in front of the turquoise sea.

Sailing in particular, one would think, should actually be the opposite: a desire for quiet escapism. Those who set sail are generally looking for a wide berth. They want peace and quiet, to find peace with themselves and the elemental experience; and at most, the odd one or two may want to reflect on their experiences at some point. Instead, every Wednesday regatta is now widely publicised. The summer cruise becomes a posterised adventure, the charter week a multimedia show. Even the winter break is being hyped up into a liked happening - trumpeted to the world on blogs, in videos, posts and pics. Sailing holidays now fill entire homepages, skippers cavort in forums with a thousand pieces of advice, and some start their own podcasts.

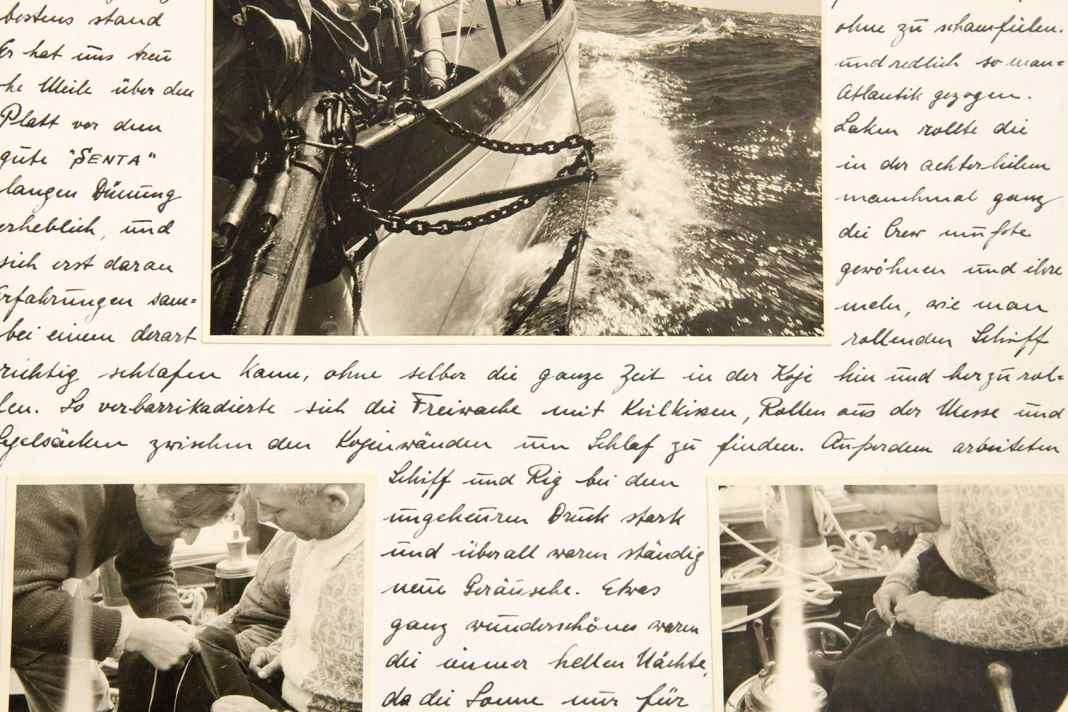

The motto is: I sail, therefore I am - and I have to report on it. This results in wonderful pictures and allows us to share in fantastic moments. The sundowner at anchor, the champagne sailing off Mallorca or the stormy ride through the Kattegat. Stories are often shared from on board, photos are posted and stories are told that are seen on various channels around the world seconds later. Today's record-breaking sailors even beam their thrilling journeys live onto the internet - something that is unthinkable in professional sport. An audience of millions follows the hussar rides of the stars via trackers, video links and satellite broadcasts - it feels like they are right up close. Today's viewers can call up routes, positions and hairy sailing moments in real time, even if the scenes take place in the stormy Southern Ocean.

Is sailing part of permanent digitalisation?

The media presence of thousands of sailors and their adventures has many advantages. You can dream and share in the excitement, you learn something new. You can get specific information and often exchange ideas with the people involved. These are the attractions of the information society: there is hardly an Anholt cruise that does not find its way into the world media.

The exhibition of our own adventures and little adventures fits in seamlessly with current events: Continuous digital sound has become the norm.

But sailing wouldn't be sailing if it didn't go slightly off the beaten track when it comes to proclaiming its zeal and producing its own streams of new ideas. And this may well be due to the fact that this pastime is essentially a quiet, perhaps even meditative affair. Sailing is by nature quiet rather than loud. It doesn't really like shouting and has always had more to do with retreating and experiencing than with making a statement and showing off. The sea and wind write their own heroic stories. And, as a rule, nobody is watching you out there on the water. Unlike in a football stadium, tennis or skiing, applause is never live and immediate.

Counter-model: I sail, therefore I am - and prefer to keep my mouth shut

The audience sits somewhere on dry land, far away from the action, while the active participants ride the waves elsewhere. And even if diabolical epics are spun in the harbour pinnacles later on - it is inherent in sailing not to trumpet its great moments. The true magic is hard to grasp anyway. Not in words, not in pictures.

However, this is probably only one of the reasons why there is now a certain counter-current to the constant media fire - by no means only, but possibly especially in sailing.

Let's call it noble restraint or ostentatious renunciation, let's call it no desire for self-promotion or simply a silence in the mast forest. But there seem to be quite a few sailors who are not only extremely reluctant to see their remarkable biographies published, but who don't even want to share a single word of their experiences with the world. Motto: I sail, therefore I am - and prefer to keep my mouth shut.

Quite a few sailors don't even want to share a word of their remarkable biographies with the world

One skipper, for example, who lives on the Baltic Sea, is now over 80 years old and could probably unpack several duffle bags full of stories from his full sailing life. But the man refuses to speak.

In the late sixties, he sailed single-handed across the Atlantic on a remarkably small sailing boat. The boat was one of the first Leisure 17s to come onto the market at the time. A boat that was only 5.18 metres long and had a draught of just 65 centimetres. A nutshell, equipped with a bilge keel and miniature cabin - still occasionally available second-hand today for around 3,000 euros. The man crossed the pond solo in order to arrive at the New York Boat Show on time with this sailing novelty. Without a doubt, the marketing coup for the new mini yacht would have been a success.

The experienced seaman and navigation officer had spent three years preparing the voyage. He finally set sail in September 1967. A 28-year-old German naval officer at the time, he had 5,000 nautical miles ahead of him. He sailed via the Canary Islands to the Caribbean, intending to cruise up the east coast of the USA to New York via Florida. A fabulous voyage, especially in such a tiny boat. But things turned out differently.

German sailor thought to be dead

After a good month at sea, the man initially moored safely in Antigua. On his journey further north, however, there was soon no sign of him. En route in the Caribbean, he had to deal with several storms, and after several search missions, the US Coast Guard considered it impossible that the German sailor and his tiny ship had survived the heavy weather.

In the meantime, the newspapers were reporting. But there was no sign of life from the German sailing esperado. He never turned up at the boat show in New York. What had happened? He had been shipwrecked in a storm off the coast of Cuba. He stranded on the island in a damaged boat, was promptly suspected of being a spy and ended up in prison. A long back and forth ensued, American journalists investigated, German and American embassies were called in - until the story grew into a veritable thriller. It took some time before the crazy German was finally bought off and released. "German sailor arrested as a spy in Cuba": The headlines during the Cold War had it all - but that's not the end of the story.

In prison in Cuba, far from being tired of sailing, the man had made plans for his return journey, which he wanted to embark on after his release - once again under sail.

He had also devised a wind steering system in Cuba: A home-made one. He then actually constructed this autopilot, bolted it to his boat and sailed back to Europe with it.

Back home, he manufactured the wind steering system in series. It became a small company, run from a remote workshop on a horse farm near Mölln. However, the gentleman in question soon sold the company again - and swapped his business and invention for a larger sailing yacht to sail his way again in the seventies.

How many more nautical miles might he have travelled after that? Where did the winds take this daring sailor? Decades later, at the age of 80, he got himself another sailing ship and set off on a cruise in the Baltic Sea. And again it was a Leisure 17 - after 50 years, he wanted to set off again on the same boat that he had used for his great transatlantic adventure. Caribbean and back, with a stopover in a Cuban jail.

Adventurer wants to remain anonymous

A life like a piece of contemporary history. And a biography that is adventurous enough to make many of today's sailing careers look like cosy bedtime stories. However, the man never said much about his travels. The detailed account of his breathtaking Atlantic crossing has never been read or heard by a wider audience. Not a book, not a post, not an article.

The man doesn't want to talk. He doesn't even want to see his name in print. He wants his sailing adventures to stay where they are: in his head. During a conversation in the German winter, he explains that all his logbooks have disappeared over the years and that there are hardly any photos of his journeys left. He continues: "Why should I remember times that are long gone?" he says. "The chapters are closed. Finished. Over." What's more, he would be very surprised at what is being blown out into the world today. The internet and modern media are great inventions, but he wouldn't want to be involved. It's an unfathomable abundance of information, images, messages and self-promotion. "I don't know where this will lead in the end."

The man says it and remains silent. He will probably take the true details of his great voyage and his life story under sail to his grave.

Perhaps because he never liked the big show. Perhaps because he is sceptical about today's euphoria of self-promotion. Maybe also because he likes Bob Dylan. The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind.

History just one of many

The well-travelled man from the Baltic Sea is just one of those who prefer to keep their sailing trips to themselves rather than publicise them. And even when they are explicitly asked about their boating adventures, some now wave them off. Their words are somewhat reminiscent of the famous and erratic sentence that Herman Melville put into the mouth of his protagonist Bartleby: "I'd rather not." In the story - the first that Melville published after "Moby Dick" - the narrow-lipped copyist not only refuses to accept his boss, but in the end also the entire (and possibly even then slightly exaggerated) world events. One day, this Bartleby simply disappeared. Without comment. Goodbye and goodbye.

An elderly lady lives on the Elbe, not far from the crooked captain's houses, who could also talk quite entertainingly from her sailing sewing box - but who also prefers to keep her life on sailing ships to herself. In the seventies, she cruised the Mediterranean for years and was one of the early women who, under the spell of Moitessier and Wilfried Erdmann, dedicated themselves to a free life on sailing ships.

She could also tell a lot - but doesn't want to

In the course of her life, she owned various wooden yachts, travelled between Greece and Spain and spent weeks in the fishing ports of the time. She lived on her ships for years, travelled the Baltic Sea and sailed to England.

A sailing madwoman of the first rank, she weathered storms on the Atlantic and made even seasoned saltbuckets turn pale when she sat at the tiller for days and nights without a break, happy and content between wind and waves.

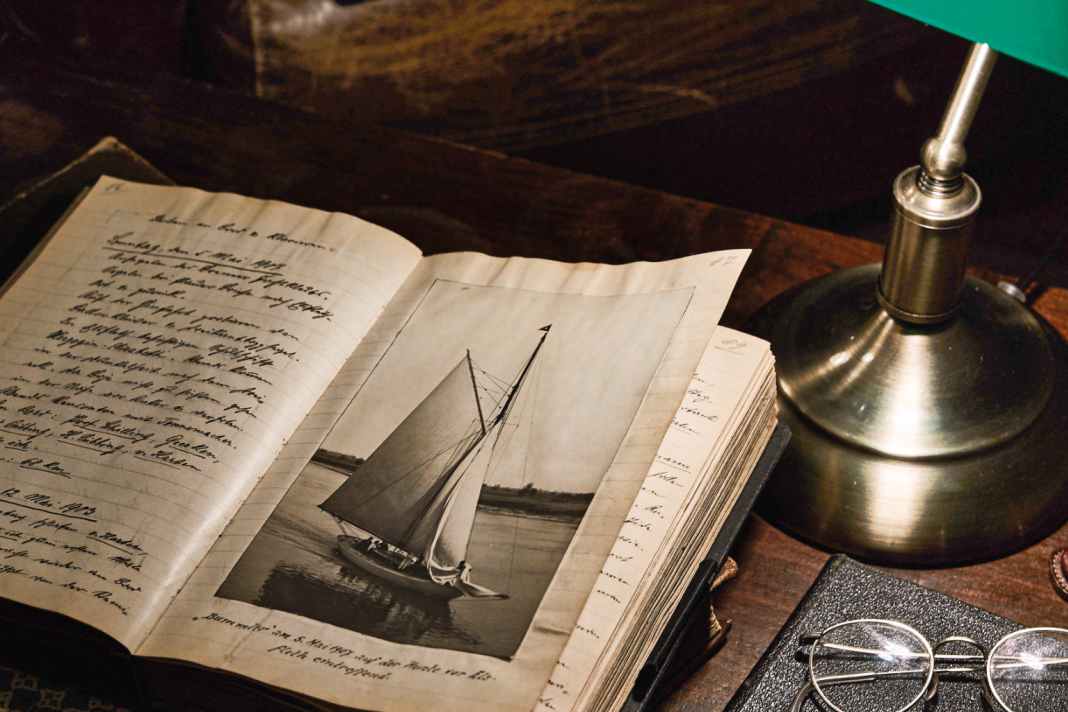

She could also tell a lot of stories - but doesn't want to. She has old photos on the table, logbooks, yellowed nautical charts and lots of handwritten notes. They are testimonies to an eventful sailing life, but she wants to keep them under lock and key. However, family and friends know the crazy anecdotes of the tireless ship's wife, who was still standing under her boat covered in dust at the age of 80 and sanding the hull - by hand. But she doesn't want her watery vita to be made public. "Why?" she asks, "I know what I've experienced. It's better to let others tell you about themselves." Her explanations sound short-syllabled. Perhaps because she knows that all the words and pictures can't really replace the magic of sailing?

There seem to be quite a few hidden stories hiding in the heads of sailors

But sometimes it's not just the old warhorses who prefer to keep their sailing escapades to themselves. A boat builder on the Weser, who is in his prime, also has a lot to tell. As a young man, he sailed in the Mediterranean and later cruised across the North Sea, from Norway to Scotland, with difficult-to-educate youngsters on board the schooner who were to be rehabilitated for a decent life at sea. Off Finisterre, he ran into a storm on his own ship, whereupon his old wooden boat took on an alarming amount of water and he and his mother had to turn back and head for Portugal.

As a boat builder, he later looked after dozens of sailing yachts, and the man also keeps a historic shipyard alive - but would do his utmost to publicise his story. The boat builder's lips are nailed shut with bronze pins when it comes to publicising his love of sailing. "I'd rather drown in the Skagerrak," is his comment.

There seem to be quite a few hidden stories in the heads of sailors. And perhaps it's in the nature of things that some of them don't want to make their CVs public. The recipe for an exciting sailing life has many ingredients, and not everyone wants to talk about it.

As Goethe once said: "No one tells another the tricks of an art or a trade, let alone those of life."

Can this also apply to sailing? Don't talk, do - because otherwise the secret will fizzle out?

So is it really in the nature of things?

However, it is also conceivable that the desire for discreet silence has other reasons - and may ultimately reflect a deliberate anti-position. The elegant abstention as a stylistic device to set oneself apart from the lowlands of modern times and digital self-promoters. Motto: Just don't swim with the masses, but secure your status through elitist isolation. However, this would turn the media's refusal into its opposite: Into what is currently probably the hippest and most vain variant of self-promotion imaginable. We know this from the old Charles Bronson and Clint Eastwood films: The coolest people are the ones who say the least.

But perhaps the biographical abstainers among our sailing contemporaries are also anticipating a trend that could at some point manifest itself in a social backlash. A collective abstinence would then emerge as an antidote to the media bombardment. A kind of cathartic resonance against the flood of images and digital self-congratulation: When nobody wants to hear and see anything - and nobody wants to report and show anything.

Film from. End of the film. This would be understandable on the one hand, but a pity on the other. Because sailing in particular can always tell amazing stories. What's more, sailing has given rise to some of the oldest, most fascinating and most influential forms of reporting.

Sailing stories as part of our culture

What would our cultural history be without the great travelogues of Magellan, James Cook, Columbus and others? What would we have missed if great explorers such as Charles Darwin, Marco Polo or Humboldt had not documented and revealed their journeys? It should be noted that the protagonists at the time went about their work with exceptional dedication and meticulousness. They kept logbooks and diaries and practised detailed and literary descriptions.

Some of the pioneers even produced artistic drawings of the experiences, animals and phenomena they encountered on exotic shores. Books such as Joshua Slocum's "Around the World Alone" later became classics, followed by books by Moitessier, Wilfried Erdmann and various other sailors who provided us with gripping reports and illuminating biographies. Sailing, the ships and the reports about the experiences associated with them - the two have always been directly intertwined.

What has become of it? Certainly, the quantity and quality of reporting have taken on completely different categories today. The ways and technologies of presentation have shifted massively - sometimes resulting in series of kitschy sunsets and cascades of sailing scenes accompanied by lift music. The hashtags, themes and motifs know almost no bounds. You can admire thunder rides through the hurricane, legendary whale encounters, but also inflationary presentations that run under headings such as "Sailing Madness" or "Dog on board".

But that's why sailing is far from getting tired of producing exciting and often extremely entertaining stories. It just tells them differently today. More diverse, more colourful, gaudier, shriller, faster. Many more people have become protagonists and actors themselves, but at the same time they have also become recipients: readers and viewers. The processes and methods of communication today have completely different patterns.

The sailing stories have remained, the ways and techniques of their presentation have changed. More colourful, gaudier, faster, shriller

All of this has inevitably led to certain excesses, and also to a challenge in the selection process - but also to more democratic conditions. The lone heroes and luminaries no longer exist today. Their former unique selling propositions have now been challenged.

Today, anyone can show, present and market themselves. Anyone can report on their adventures, dreams and experiences - unfiltered, at will, and in front of a global audience. One click and the holiday trip is online. A swipe of the mobile phone and the latest harbour commentary is posted.

Like so many things, the adventure of sailing is no longer a domain reserved for experts. It has become virtually transparent. And sometimes a quick selfie can speak volumes and the breathtaking photo of an ordinary amateur sailor can win first prize.

Sailing still writes the best stories

The sailing world has certainly not become more manageable as a result. Perhaps a little crazier and faster, a little more garish and louder, but by no means necessarily flatter. As we all know, the sense and sense of reporting is debatable - as it always has been. The same goes for the advantages and disadvantages of sharing your passion with as many people as possible.

One thing is certain: When it comes to the content of life and its portrayal, we can marvel today as we once did - and be certain of an old truth. Sailing still writes the most beautiful stories. The sea and wind still provide a brilliant backdrop, and incredibly powerful plays are still being performed on these beloved ships today.

But who do I tell?