An industrial estate in Västervik, Sweden. Long corridors lead through the logistics centre, with a door every few metres. Above one entrance is the word "Yrvind" - whirlwind - and a piece of wood dangles from the door with the inscription "Trägen Vinner", which translates as "Tough Vinner":

Perseverance leads to the goal"

The modest entrance leads into the workshop of the grand master of microboats: Sven Yrvind. The living legend is now 83 years old and has been building very small, seaworthy boats for decades, which he still plans, builds and sails on the world's oceans.

Yrvind opens the door, his white mop of hair and beard covering almost his entire face, his eyes twinkling kindly through the lenses of his nickel glasses. He is dressed in blue work clothes, a rope trims his trousers to waist height. The self-taught boat builder is in surprisingly good shape for being born in 1938.

After a brief welcome, the way into the workshop is clear. Brightly lit and more of an artist's studio than a small boatyard, his current project, the sailing canoe "Exlex", hangs here on robust chains. Yrvind walks nimbly around the hull, showing details, explaining connections and taking material out of the cupboards to illustrate. Then he suddenly stops, falls silent and thinks. "I've just found the solution to an old problem," he says with a smile and continues to explain. Typical Yrvind, in whose head a multiple problem-solving machine always seems to be running.

Having already travelled the world's oceans with numerous self-built microboats made from various materials, Yrvind has been working on the 6.27-metre short and 1.40-metre narrow new build every day since August 2021, which will take him non-stop from Ireland to New Zealand and on a direct course from Dunedin back to Europe. He reckons it will take 200 days to cover the 15,000 nautical miles, which is a distance of 80 miles.

Yrvind had already made two attempts to sail to New Zealand, but cancelled the last trip in 2018 after a stopover in Madeira and having to weather violent storms in the Bay of Biscay.

6.27 metres- almost a yacht for Yrvind

At 6.27 metres, the current small cruiser design in the Västervik workshop is slightly longer than the previous models and is designed to run at an average of three knots. "A double-ender is the better choice to achieve a balanced ratio of length and speed," says Yrvind, who refers to the Froude number, a physics parameter according to William Froude (1810-1879), which is a measure of the ratio of inertia to gravitational forces within a hydrodynamic system. It is used in hydrodynamics to describe the bow waves of ships.

Yrvind has always adapted the design of each of his boats precisely to the respective project. "During each trip, I was already working on the next design and looking for optimisation. That's why I can now draw on so many ideas to develop the perfect boat," says the energetic tinkerer. And with his mischievous smile, he adds:

Even now, I'm already working on a new design for the next project."

The fact that the whirlwind of an idea in his head actually turns into a real hull, which he then sails across the world's oceans himself, is due not only to his iron discipline but also to the wide range of skills he brings with him from over 60 years of practical experience. The small boat sailor has learnt the nautical trade and a wide range of craft skills from the bottom up.

An amazing sailing life

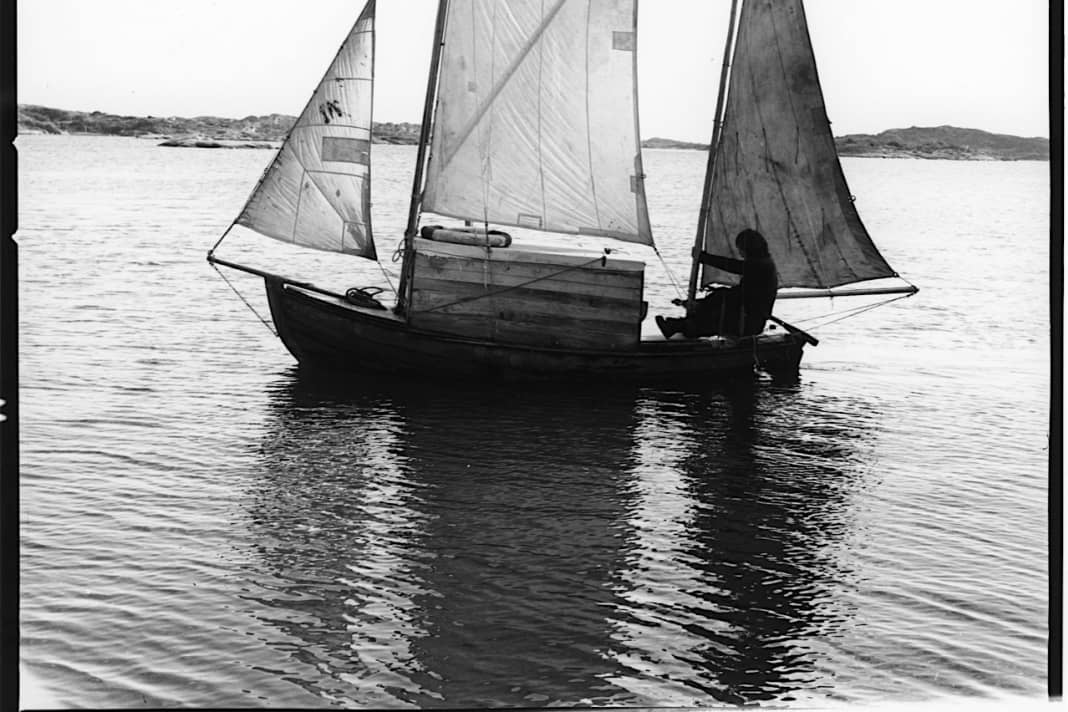

Yrvind started sailing as a teenager and his first single-handed trips took him from the Gothenburg archipelago through the Kattegat to Denmark. After school, he worked in a locksmith's shop and later travelled to Germany and Austria, working on building sites and handling timber and other building materials. Finally, in England, he helped in shipyards and repaired wooden hulls and rigs, and in the chemical industry he learned to weld steel and aluminium.

He continued his effective self-study in the USA with what were then revolutionary construction techniques, which he learnt in 1975 at R. Newick's America's Cup workshop in Newport. They experimented with Kevlar, epoxy and carbon, and the first composite multihulls were launched onto the race course from here. It is therefore not surprising that Yrvind can handle a wide range of construction materials and knows how to utilise them for his latest "Exlex" project.

Small cruiser projects by Sven Yrvind

A tinkerer down to the last detail

Yrvind's extensive experience is also evident in small solutions. For the screw connection of the covers in the boat, he mills the nuts himself from an aluminium-bronze alloy in order to avoid stainless steel as a material for both the screws and nuts. Such connections are prone to jamming, which destroys the thread.

For the sandwich hull laminated with epoxy resin, the self-builder uses a core of PVC foam (Divinycell H), which he uses in a density of 80 to 400 kg/ m3. This material is ideal for use in tough conditions and is very light in weight. The inner hull shell and bulkheads are reinforced with carbon fibre mats.

On the last boat, the core material was only half the density, so I had problems with condensation before Iceland. I want to avoid that now!"

Yrvind makes eyelets and cleats on the hull from a rope loop that is hardened and moulded with epoxy. In his experience, this is the best way to integrate attachment points in a sandwich construction without compromising the structure and strength of the hull shell.

He carries out material and capsize tests on each hull himself. To do this, the hull is capsized in the harbour by a helper and a crane and then righted again. Meanwhile, the skipper lies in the hull and checks the tightness and fit of his safety harnesses. Instead of a keel weight, the 350-litre supply of drinking water is used as water ballast. Yrvind wants to top up what he has drunk with salt water.

The centreboard of the new "Exlex" is positioned in the bow, made of extremely strong epoxy laminate (G 11). It is intended to ensure better upwind performance; drifting due to headwinds and currents is to be expected on the planned route. The centreboard box is installed in the bow section to save space. A variant that Yrvind already tested on two of his boats in the mid-1980s, the open experimental boat "Cykel-Bris" and later the 4.80 metre short "Amfibie-Bris", which he sailed from France via Ireland to Newfoundland.

Unlike the "Exlex" predecessors from 2018 and 2020, which had problems steering the boat from the bunk, this time the rudder stock is guided into the hull by a coker and the forces are transmitted by a double quadrant. Dyneema cordage then serves as the steering cable, and the steering system can now be conveniently controlled from the bunk via pulleys in the aft section and amidships. "I can read the rudder position on the pulleys. It's a great advantage to be able to stay below deck in heavy weather," explains the experienced offshore sailor.

The rudder blade will be made of bronze, and two small fins made of epoxy laminate will prevent ropes from jamming the spade rudder. The "Exlex" will not have an autopilot; the course will be maintained via the trim of the sails.

Alone- but not lonely

Although the Swede lives and works mostly in seclusion, he does not keep his expertise to himself. Lectures and seminars were an integral part of his work before the pandemic and a good source of income - as a speaker, Yrvind knows how to convey his experiences in an entertaining and practical way.

The loss of income during the coronavirus period is still a problem for Yrvind, who lives and works on a very small budget and does without sponsorship for his projects. He is therefore more dependent on supporters than ever before. He already provides his reward on his YouTube channel. Here, the expert opens the digital door to his workshop to over 17,000 followers and lets them share his construction progress and special solutions to problems on a daily basis.

This forum is also used to discuss, talk shop and maintain a lively global exchange. "Over the last few days, I have been discussing e-power with my community and have come to the conclusion that the new 'Exlex' will have an electric drive. For harbour manoeuvres only, of course. With 300 to 600 watts of power, the solar power is sufficiently dimensioned for this, and lithium-ion phosphate batteries will be used for storage."

Two masts next to each other

However, the wind will continue to be used as the main propulsion system. For this purpose, there are two free-standing masts next to each other at the front, each with a three square metre lugger sail. A third mast with a two square metre sail is to be rigged aft behind the rudder.

The cloths are made in Karlshamn in Blekinge in southern Sweden by Hans Hamel. The sailmaker with German roots is well known to cruising sailors and has saved many a holiday trip with expertly placed stitching. Hamel has been following the ambitious projects of the microboat designer for a long time. To make his contribution, he provides material and labour free of charge.

Thanks to the lugger rig, only one third of the sail area is driven in front of a rather short mast - a load distribution that provides more security against breakage. According to Yrvind, the use of two masts brings further advantages: better course stability on downwind courses and space-saving installation in the hull without sacrificing the minimum space in the living area. The aft mast is made of fibreglass and houses the radio antenna.

Compared to previous designs, Yrvind has made the interior of the boat more spacious and cosy. Divided into four sections and separated by bulkheads with round passages, there is the forepeak with centreboard locker and a hatch in the deck, a so-called captain's cabin with a wide berth, the saloon or crew area, where one person can just about sit, and the aft section with helm quadrant and deck hatch.

Of course, the 'Exlex' also has headroom - when the hatch is open," says Yrvind with a grin.

A bilge and bilge pumps are installed both aft and forward, as water can enter through the hatches when boarding and disembarking. In the captain's cabin there are many stowage compartments on the sides, and the superstructure windows are designed to provide an all-round view.

"With this sailing canoe, I don't want any disruptive elements on deck, but an open area so that I can move around easily. Even if the distances are extremely short, of course," explains Yrvind. What's more, there is no risk of dramatic damage from large breakers or capsizing.

Yrvind wants to manufacture the hatch covers in composite construction, several solar panels are to be mounted on the superstructure roof, and the belts for rigging will be stowed underneath.

Yrvind is not bothered by the fact that even expert critics consider the massive material thicknesses to be excessive:

I want to feel safe, even in a storm in heavy seas. Then I strap myself into the bunk, read lots of books and write down my thoughts about the next project."

The small cruiser designer is self-taught

The self-taught genius surrounded himself with literature such as specialised books and scientific treatises, and not just on his sea voyages. More than 10,000 books fill the curving shelves in both his home and his workshop in Västervik. He has stored just as many works in digital form. Thematically, all academic disciplines are represented: Physics,

Mathematics, chemistry, medicine and the humanities. And of course many volumes on shipbuilding, nautical science, engineering and meteorology. In addition to Swedish works and translations, there are original editions in English, German and French on the shelves. All foreign languages that Yrvind has mastered in word and text.

Yrvind acquires the knowledge he doesn't get from between the many book covers through up-to-date online research. Unlike many of his peers, he finds modern media and digital content enriching - and not overwhelming.

Self-study with learning disabilities

Due to a diagnosed learning disability and a pronounced stubbornness, the young pupil Sven found it very difficult to find his way into the mainstream school system.

For a state-recognised dyslexic, I've actually always been in a good position"

Yrvind continues: "I just need enough time and want to be able to follow my own train of thought, then I can solve even very complex tasks."

Yrvind has actually given his entire life to finding the ideal answer to material or construction questions. That is why the total number of hours or costs for such a project are not decisive for him. "I'm busy 24 hours a day with the current project or the next one. If I get a brilliant idea while I'm falling asleep, I get up again and think through all the details during a night-time walk."

For him, building boats is not a job or a pensioner's hobby, it is his way of life. However, he does not put any pressure on himself to finish a boat project quickly. Yrvind answers the frequently asked question about when the boat will be finished in a friendly manner:

When it sails out at sea!"

In any case, he would like to undertake the first test drives and capsize trials in the 2023 season. And of course, the restless visionary doesn't want to let a minute go by unused. That's why there are six clocks in his workshop - the admonition to "Carpe Diem" ticks by every second.

Fitness despite old age

So it's no surprise that the tinkerer's entire day is meticulously planned. In addition to working in the workshop, he goes jogging, cycling and swimming. Only the curing times for epoxy and the associated work disrupt his timetable, so he goes straight to the boat at night if necessary.

"Lots of exercise and a fixed rhythm are fixed conditions for being able to realise my projects," reveals the master microboat builder. "And a healthy life with valuable nutrition - I only eat one meal a day."

Typical Yrvind, purist right up to the edge of the plate. At 11.30 a.m. on the dot, he takes the compressed air gun and cleans his clothes of the dust that spreads over everything after just a few minutes, switches off the light and locks the door.

"Perseverance leads to the goal" - the wooden sign with the motto is still a reminder here, even though Yrvind has long had this virtue in his genes. But he doesn't really want to reach his destination, because then everything would be over. And that is far from it for the old Swede.