Off Elba in the Mediterranean, 6 Beaufort true wind and eleven knots of speed through the water make for powerful whistling on deck. Waves are foaming. A good 50 tonnes of ship spread over a length of almost 30 metres are working mightily in the blue sea.

Spray lashes against the deck in a few waves, the cruising yacht "Polina Star IV" pushes hard. The unreefed main and the cutter jib stand like planks. Something is happening here, enormous forces are acting on the carbon mast of Hall Spars, which stands on the keel, and on the entire hull. It somehow feels enormous. Powerful. Loud. Impressive.

It's pretty quiet on board the cruising yacht- and safe

The next route leads below deck to catch a glimpse underwater from the hull windows to leeward. And the sensation there hits the visitor completely unexpectedly: there is complete silence. No creaking or rattling, no squeaking, no rushing of the water outboard - simply silence. Decoupled as if in a space capsule, propelled by a seemingly unknown force, this mighty machine moves its passengers through the sea. However, this movement can only be recognised by those who look out through the windows in the hull and see the water rushing past.

Other interesting cruising yachts:

Because even the movements here, at the centre of power so to speak, are rather calm. Only everything is crooked. But that doesn't matter, because the next handhold is not far away. Everywhere in the ship, the hand searching for support finds a ledge, a tube or a handle. "Alessio in particular attached great importance to this," reports Arjen Conijn, head of the Dutch shipyard Contest Yachts, who is also on board.

The construction was a matter of trust

This Alessio's surname is Cannoni and he is a man with a lot of experience. And he is the captain whom the owner trusts unconditionally. He had a virtually free hand during construction. The following story from this phase illustrates the extent of this trust. When it came to designing the sail plan, a furling mainsail came up: "I explained the advantages and disadvantages of such a setup. And then I said: If the boat gets a furling mainsail, I won't be its captain," Cannoni recounts at dinner after the trip. "After a long pause, during which everyone at the table was silent, the owner finally said: 'Then just battened down with a Park Avenue boom'." Finally, the principled Italian adds with a grin: "That was a load off my mind. Those were long minutes of silence."

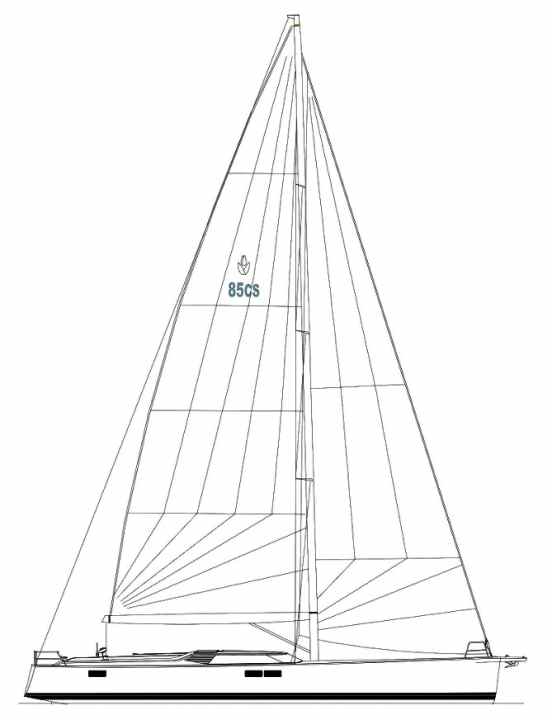

The result: a full 188 square metres of North laminate are now emblazoned on the mast with a 1:2 ratio halyard, which can be driven at the foot of the mast via one of the four hydraulic 88 mm Lewmar winches. For manoeuvres such as setting sails or jibing, the starboard generator can be started if speed is of the essence. A hydraulic pump is flange-mounted to it so that extra power is available for fast work. However, the electric pump alone also provides plenty of pressure on the drums.

The "Polina Star IV" can also be sailed with a small crew

In addition to the four on the mast in the cockpit, there are a further eight, four of which are in the large 111 version. There is also a story about this: this time it was the owner, who sails regattas himself and observed on the previous ship that his captain liked to work with barber winches on the foresheets. The owner thought that he would surely need extra winches for this. The captain agreed, and so a drum was added to each side.

However, the sail layout works excellently. Yes, there are quite a few lines on deck, which we are no longer used to in the post-Wally age. However, the ship is easy to sail, even with a small crew. For example, the lines for the gennaker jib, which are led aft, are also used as bull stays in their spare time, the halyards are attached to the mast and halyard blocks are not used. Everything is very traditional.

"It's worked well for centuries, there's no need to change it," the captain is convinced. Of course, if you like it better with even more hydraulics and little buttons on the steering column, the shipyard will give you that too. Of course, there is little in this category of ship that doesn't work.

The cruising yacht is easy to sail

In any case, the sailing characteristics prove the very opinionated Cannoni right. On the cross, the yacht can be steered with great pleasure on the windward edge. There is even pleasant rudder pressure thanks to the typical Contest gimbal transmission. Due to the enormous rigidity of the construction, the boat communicates its state of mind to the helmsman.

Anyone expecting to drive a coach will be disabused; this is more of a sporty luxury saloon - one that you can drive yourself instead of just being chauffeured. "It's clear: a cruising yacht like this has to sail well. Otherwise the owner loses the fun and buys a motorboat. If it doesn't sail like a yacht, what's the point of such a large sailing ship?" the captain rightly asks.

And how she sails. At the helm, there are still a good five metres of ship behind you, and almost 25 metres ahead, with even the smallest steering movements shifting the horizon in one direction or the other. The tell-tales provide information about the current at the sail. Even in gusts, the 50-odd tonnes lie on their side and the Contest picks up speed. It's hard to believe, but even such a large ship can feel like a 45-foot yacht.

The greatest strength of the "Polina Star IV"? Its versatility

The sail plan places great emphasis on the versatility of the cruising yacht. The genoa and cutter jib are firmly attached to their own furlers. And a small and a large gennaker as well as a code zero are waiting to be used in the extremely spacious forward sail area. Meanwhile, the main has three reefs. The result: "We have a suitable setup from 5 to 50 knots of wind," says Cannoni happily. The genoa and main have a sail load factor of 4.8, which is within the range of a performance cruiser.

As the harbour of Scarlino north of Punta Ala approaches, the engine is started. The only thing you notice on board is that the fuel consumption indicator on the Volvo display jumps from 0.0 to 2.2 litres per hour at idle - nothing else. The engine runs. There is no vibration and certainly no noise. It's even a little scary, because the lack of feedback to the ear makes the driver doubt that the engine is working.

When it comes to sound insulation, the shipyard has always taken things to the extreme. It starts with the fact that the entire engine compartment is one of a total of five watertight compartments. But the sound insulation itself is also particularly effective and carefully designed.

Technical refinements on board the cruising yacht

The engine is decoupled from the drive train with a thrust bearing, which in turn allows the engine mounts to be very soft, preventing vibrations from being transmitted to the hull. The water and hydraulic pumps are also installed in the engine room, as are the high-pressure pumps for the two water makers, which are mounted in the crew area in the foredeck for easy maintenance.

Even the mast, which is usually the powerful horn section in the ship's sound orchestra, remains silent. Of course, special door catches also prevent rattling, and all floorboards rest on rubber feet. However, a prerequisite for an otherwise quiet ship is a rigid hull. Nothing creaks because nothing moves in the swell.

Contest Yachts achieves this by building the hull and deck using the so-called one-shot infusion process. This results in very rigid structures that also allow a great deal of freedom in the interior design, as the designers are flexible in the placement of structural components such as the bulkheads.

The "Polina Star IV" is characterised by the ideas of the captain

Once the lines are secured, Captain Cannoni begins a tour of the ship. Everything here bears his signature. And this in turn is characterised by his unfortunate experiences on the previous ship, the "Polina Star III". For example, all cabins have an escape hatch with a pull-out ladder built into the ceiling. After all, such a hatch at a height of more than two metres is of no use if you can't reach it if the worst comes to the worst.

The floorboards are all secured with a toggle lock, unless they are permanently bolted down. "You can't move through the ship if the boards float up in the event of water ingress," reports Captain Cannoni from experience. The VHF radio system has its own battery, which is installed high up in the saloon. This means that communication remains intact, even if the rest of the electrical system is already under water.

The central bilge pump generates a vacuum in a line that runs through the entire ship into each bilge section. The valve for opening the suction is installed in the area behind it. This allows the forepeak, for example, to be sealed watertight and drained from the crew quarters. The life jackets are located next to the companionway. In addition, there are further lifejackets in each cabin in case it becomes necessary to exit through the emergency hatches in the deck because the route through the companionway is impossible, for example due to a fire.

Lots of safety on board the cruising yacht

So much for the safety features for emergencies. To prevent this from happening in the first place, the shipyard has come up with a whole range of solutions together with Cannoni. The fuelling system, for example: two large tanks supply a day tank. This is done through a powerful filter and, if necessary, the transfer is only possible using gravity. From there, the diesel passes through filters to the generators and the main engine. The filter for the 260 hp Volvo is switchable and therefore redundant.

The shaft bushing is grease-lubricated. This is unusual nowadays, but it is the usual solution at Contest: "We have looked at many other seals, but this seems to us to be the most solid. You can just squeeze grease in and it's tight," says Arjen Conijn, the shipyard's CEO. The captain also confirms this: "So far everything is tight, no problems."

And the list goes on and on. The Contest 85 is a surprisingly uncomplex ship for its size. Below deck, for example, the captain relies on natural ventilation; although there is air conditioning, it is almost never needed. The concession: instead of a smooth foredeck, there are now six fans. However, they do have a practical use, says the captain, as they provide support on the way across the foredeck. However, the scuttles are not aesthetically pleasing.

The cruising yacht is to go on a world tour

If technology is installed, then it is redundant, such as the watermakers and generators. Both are identical in design, making it easier to obtain spare parts. The owner's plan is to go on a round-the-world trip, during which he will be on board a lot and also steer. The cruising yacht therefore had to sail well and be comfortable at sea.

The shipyard and designers achieve the latter through the so-called centre-line strategy. The galley, beds and wet cells are all installed as far as possible along the ship's longitudinal axis so that less movement of the ship is felt when showering at sea, for example. The cupboards also open as far as possible in the direction of travel or vice versa so that the contents cannot fall out when the ship is in position.

All bunks have leeboards, all corners are round. Incidentally, these are not only attached as mouldings at the joints, but are laminated as an entire profile in special moulds. This is a very durable, but also complex production method, as a separate laminating mould has to be built for each corner, in which the individual veneer layers are glued together. Of course, this is also done under vacuum. The same applies to the fastening of the teak deck; here, too, gluing is used instead of screwing for the sake of durability.

The "Polina Star IV" is unusual, but solid

From the shipyard's point of view, the "Polina Star IV" is certainly unusual. It is the largest ship that the family business has ever built. But it also shows how seriously customer wishes are taken in Medemblik. "Of course, a fixed bimini like that isn't very nice. We also don't like the dorade vents on the foredeck. And contests are usually dark blue. But the customer wanted it differently, and then it's simply our job to realise it in the best possible way," explains Arjen Conijn.

The 85 CS is almost reminiscent of explorer yachts: the simple robustness that runs through the entire ship, the rock-solid construction, the redundancy of important systems, the sail plan that is always easy to operate and the low-maintenance white hull that stays cooler in warm climates.

The shipyard realised all of this professionally, as if the construction of such a special cruising yacht was an everyday occurrence. But it wasn't: for example, a boat of this size simply doesn't fit through the lock that separates the shipyard from the IJsselmeer. The "Polina Star IV" was transported to the open water on a pontoon, from where it was launched into its element. "That was at six in the morning," recalls Arjen Conijn. "I was unable to be there that day, but my father was there at the crack of dawn and took photos. He sent them to me straight away. That's how it is in a family business."

You can hear a little bit of pride in the stories of the captain and the shipyard manager. And quite rightly so, by the way: because one of them has made a ship a reality for its owner, on which he can actually realise his long-cherished dream of sailing around the world, which had been postponed for years due to adverse circumstances.

In 60 years, the others have developed a small family business into a renowned shipyard that can build great ships like the cruising yacht "Polina Star IV" and find customers for them.

This article first appeared in YACHT 15/2019.

Technical data Contest 85 "Polina Star"

- Designer: Judel/Vrolijk & Co

- Total length: 28.65 m

- Hull length: 25.85 m

- LWL: 23.17 m

- Width: 6.40 m

- Draught/alternative: 3.79/3.28 m

- Sail area downwind: 330 m²

- Weight: 52 tonnes

- Ballast/proportion: 18.5 t,36 %