The end of the world in Flensburg. Low clouds quickly gather against a blue-black sky, the wind howls in the rigs, showers descend. At the museum jetty, thick drops patter onto a cream-coloured deck. But they can't stay there for long, because it curves in a semi-circle; and as quickly as the water lands on it, it runs off again. "Whaleboat weather!" Owner Roland Fiebig stands grinning in the spacious cockpit of his "Coelnamara" and wants to get underway. A whale doesn't care about the weather. Fiebig's words come as no surprise: the whale is a special sea creature.

Whaleboats have their origins in the 1930s

His story begins in the early 1930s: "For many years, I have been working on the idea of obtaining the documents for the creation of a cheap keel class for coastal areas." When he wrote these lines for the 18/1932 issue of YACHT, the renowned ocean sailor Hans Domizlaff had already overcome the biggest hurdle to the planned project. Wal 1 won several regattas in the very first summer and proved its seaworthiness on a stormy voyage around Zealand.

Other interesting classics:

As a result, its genesis as a popular boat seemed inevitable. The 1932 Sailing Congress recognised the whale as a new standard class and the fleet grew rapidly. But then came the war, from which the whale would never recover. And even its history seems almost forgotten today.

Here, on the cold and wet Flensburg Fjord on board the "Coelnamara", the classic comes to life again. The rattling mainsail rises from the wooden mast, a red whale wriggling in it, the number 13 below it. As the eye sweeps across the deck, it quickly becomes clear that a whaleboat has been preserved in its original condition - a stroke of luck, as anyone who delves further into its history learns.

The classic can withstand difficult conditions

After the First World War, sailing in Germany is slow to get going again. The yacht fleet is decimated and money for new builds is scarce. Hans Domizlaff wanted to solve the problem. "I am thinking of the coastal clubs that are particularly close to me, which are being crushed by the hardship of the times and are in danger of being lost to sailing due to the lack of a cheap type of boat; and it is precisely these coastal sailors who are the most valuable preservers of sailing tradition."

In addition to the approximate dimensions, the requirement profile was clear. The boat they were looking for had to be cheap, made for the rough conditions on the open sea and - so that the youngsters would enjoy it - fast. It also had to be suitable for travelling, i.e. a cabin with fixed berths and rudimentary fittings.

On the classic "Coelnamara", this equipment is preserved as it was on the day of launching. According to the building regulations, this included "sleeping accommodation and cooking facilities for at least 3 people". Furthermore, a wardrobe, chart and crockery cupboard, wall shelves with plate and glass racks.

As an advertising psychologist and founder of brand technology, Hans Domizlaff knew at the time what effect it had when he presented a finished boat rather than a proposal on paper to the Sailors' Day. And so he set about developing it himself. He exchanged ideas with Henry Rasmussen and eventually ended up with the Kiel naval architect Heldt.

Inventor Domizlaff has precise ideas and concepts

And Domizlaff has plenty of ideas. Firstly, there is the price. The boat should be cheap and yet of high quality. "The materials and construction must be the best possible," is his credo. The solution to the dilemma is ultimately provided by the design of the classic whale.

As an articulated boat with an under-bolted keel, the whale is already more economical to build than a conventional round bilge. The round deck saves even more hours. However, the so-called whale deck also caused a fierce controversy about the new class. Domizlaff defends the style-defining element - whether it was named after the boat or the boat was named after it is still a mystery today - because in addition to huge cost savings, it has numerous advantages.

The round shape reveals its advantages at full speed

"As soon as the boat is underway, i.e. heeled, the Waldeck is easier and more comfortable to walk on upwind than a normal deck. It is more stable and provides good protection against overflowing water, which is immediately channelled to the side." In addition, according to the father of the whaleboat, the volume of the boat's interior is so large due to the curved deck that a high superstructure is unnecessary. "I don't understand how anyone can find the usual high cabin beautiful."

The jib is now also on whale 13, and the foresailor is happy to be able to take a seat in the cockpit. Because without a position and in wet conditions, walking on the Waldeck takes some getting used to. On the other hand, there is a dinghy feeling on the bay and high edge as the whale stretches its nose towards the harbour exit and confidently shakes off the first spray from the hump.

The construction does indeed look futuristic 90 years ago. On closer inspection, its aesthetics are indeed reminiscent of a whale, even though the buckling frame construction creates a distinct angle in the ship's side. However, Domizlaff and Heldt manage to avoid a sharp chine with a trick.

The classic has many advantages in design

"Eventually I came up with the idea," Domizlaff writes, "of moving the chine stringer to the outside of the whaleboat - similar to motor racing boats. This gave me a particularly strong plank that left enough flesh to plane the chine round. The rounded chine was now completely invisible in the sharp foredeck. And the unsightly sharp edge also disappeared aft." The disadvantages of the buckling chine were thus eliminated, but the advantages remained - especially the higher strength.

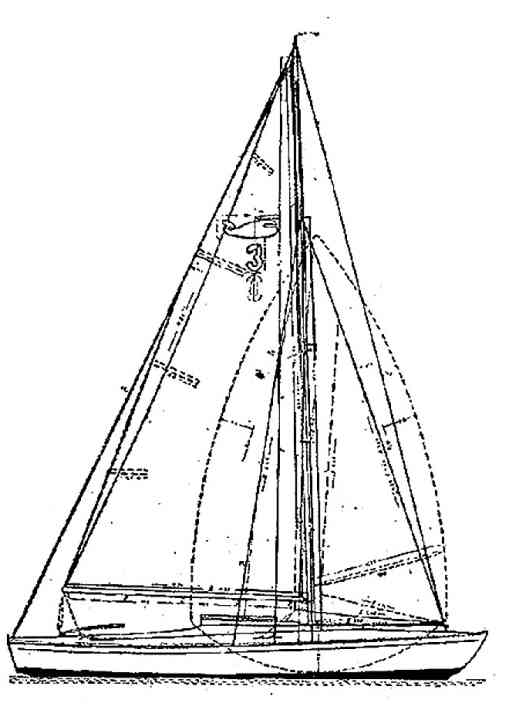

Numerous details were new at the time. The rigging is optimised for single-handed sailing. The jib has a boom that is sheeted on a leeward carriage. The mainsail can be reefed upright from the companionway so that the cockpit - which, according to later class regulations, can also be self-bailing - does not have to be left at sea.

The whaleboat is built in mahogany on oak. The rig with its eleven metre high, hollow spruce mast is driven with two forestays, upper, middle and lower shrouds as well as backstays and backstay. The sails include a mainsail, jib, genoa, storm jib and spinnaker.

The classic whaleboat comes up trumps in bad weather

"The whaleboat is first and foremost a cruising boat," writes Domizlaff after the first summer with Wal 1, which is christened "Wal" on 3 April 1932 in Arnis at the Matthiessen & Paulsen shipyard. "Its real element is bad weather. Unfortunately, most sailors still believe that the most reliable heavy weather yachts have to look like troughs. That is wrong. The real seagoing vessel is characterised by the fact that it keeps a good speed ahead for longer than all others in increasing swell high up in the wind without taking on water. This is the special achievement of the whaleboat, as anyone who has ever sailed one will confirm."

At the stormy Kiel Week in the summer of 1933, today's classic makes a name for itself due to its heavy weather characteristics. On the second day, the wind was blowing out of every buttonhole. An easterly south-easterly with 7 to 8 Beaufort forces some crews to their knees. But the group of whaleboats completed the course routinely.

Whales 1 to 10 were launched at Matthiessen & Paulsen between 1932 and 1935, with Domizlaff subsidising the construction with 500 marks per boat. "The inventory includes oars, dolphins, anchors, etc., i.e. the usual nautical equipment. With the exception of the sails and cushions, the last two whaleboats cost 2,400 marks each," Domizlaff wrote in YACHT in 1933. With plans, building instructions and surveying regulations, the boat can also be built by the owner himself or by another shipyard: "The cost price is charged for the tracings of the construction drawings. A licence fee is not charged."

In his standard work "Racing, Cruising and Design", published in 1937, the British star designer Uffa Fox describes the whale with verve in his 13th chapter, but this is not to mean good fortune for the young class. Two years later, war broke out.

The successor is coming - and the whaleboat is becoming increasingly rare

When it became possible to spend leisure time on the water again in the 1950s, the whaleboat, in retrospect, had the best chance of building on the success of the early years. The first ten boats survived the war and the whales were launched together during the first few weeks in Kiel. But in the second half of the fifties, the Nordic folkboat appeared on the scene. It is even simpler to build and sail than the whale and replaces it as the people's boat.

Nevertheless, for a while it looks as if the whaleboats are experiencing a renaissance. Time and again, new boats were built, often under their own steam. In Eckernförde, for example, master watchmaker Rudolph Eckstein launched two whaleboats in 1959, one of them, today's "Coelnamara", for himself.

Eckstein is building in the anteroom of a carpentry workshop, assisted by neighbour Gernot Kastka. He is now 80 years old and sits on board today as Wal 13 shoots across the choppy Flensburg Fjord. "We started in 1959. We met every day after work and worked on the boat, usually until 11 pm. On Saturdays, we worked until midday, then we worked on the boat and on Sundays in the mornings too," remembers Kastka. "It took us two and a half years."

There were also several new builds in the GDR, of which two excellently preserved examples, the whale 12 "Beluga" and the whale with the GDR sail number 119 "Kimm", are still sailed in northern Germany today. Three newbuildings are known from Switzerland, which were built in the second half of the 1950s at the Rudolf Fürst shipyard in Romanshorn on Lake Constance.

Entire fleets were formed in South America, and in Argentina a related class of boat was even created in the form of the Grumete, designed by Germán Frers Sr. based on the whale. However, the whale seems to be almost extinct in its native country. At the Kieler Woche in 1961, there were still five boats at the start, but the following year there were only two.

Whaleboats are a valuable rarity today

Until the 1980s, there was an annual whaleboat meeting. And when the Circle of Friends of Classic Yachts was established at the beginning of the nineties, its classic yacht meetings were once again an occasion for owners to come together with their boats. In 1997, the successor to the Matthiessen & Paulsen shipyard donated a whaleboat prize, which was sailed for the last time in 1999.

Today, it is hardly known where the whale classics have gone. A few of them are in good hands in the classic car scene. Whale 13 is probably the most original of them. On board, Gernot Kastka feels completely transported back to the 1960s, when he went on long trips with Mr and Mrs Eckstein and their son. "There was no engine or tarpaulin," says Kastka, but he never felt cramped on board.

Owner Roland Fiebig found the current classic in a pitiful condition at the Eckernförde Siegfried shipyard in the early 1990s and took care of it. A previous owner had baptised the vessel with its current name, which means "sound of the sea" in Gaelic. Fiebig considers life without a whale to be pointless. The sound of the sea, he says with a grin, is nowhere better heard than on the back of a whale.

Technical dataWhaleboat 13 "Coelnamara":

- Idea and concept: Hans Domizlaff

- Designer: Naval architect Adolf Heldt

- Builder: Rudolph Eckstein

- Year of construction: 1932/1959-62

- Hull length: 8.50 m

- Width: 2.20 m

- Draught: 1.30 m

- Displacement: 1.32 tonnes

- Sail area: 27 m²