Wolfgang Kalensee was comparatively young when he helped a friend slip up in Rostock's museum harbour, "right in front of her beautiful spoon bow", as he says today. "Her" refers to his current boat, the "Doric" - a beautiful, striking design by American Bill Tripp Jr. As a trained boat builder, Kalensee knew exactly what he was getting into. And was better able to distinguish between dream and reality, or realisability and restorability, than many others who had already lost their head, neck and bank balance over a yacht.

Love at first sight is actually different, admits Kalensee. "The condition of the aluminium yacht 'Doric' left a lot to be desired at the time" - as if someone had seriously or criminally neglected their duty of care. The owner at the time, unlike himself, obviously came from a more theoretical background. Externally, the aluminium yacht was the least of the problems. Rust and woodworm are known to have little chance with aluminium; the expert only discovered aluminium corrosion, real "attacks", on four bronze fittings. Otherwise, the substance was solid - as if built for eternity and timelessly beautiful.

A special aluminium yacht

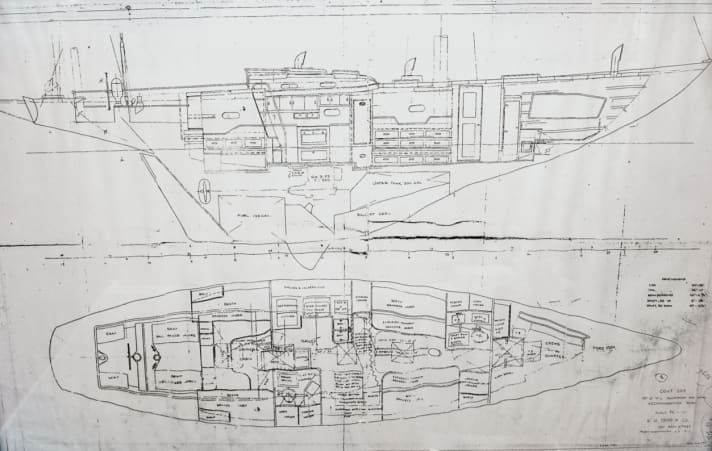

"I had never seen a ship like the 'Doric' in Germany before": a cruiser/racer with wide running decks, long overhangs and an ergonomic, almost futuristic-looking superstructure. The Yawl was built in 1966 by Abeking & Rasmussen near Bremen as a regatta yacht for the American Stanley Tannanbaum. "The second ship ever," adds Kalensee, "to be built from aluminium at A&R." Number 1 had been the "Germania VI" for Gustav Krupp.

More on the subject of aluminium yachts:

One winter later after the first rendezvous, the aluminium yacht "Doric" was still moored in Rostock's museum harbour. No longer high and dry, the current owner continues. He had lost sight of her, but never completely forgotten her. The friend had unhitched his boat and gone alongside the "Doric". Kalensee helped lay a new teak deck and had to climb over the ship a few times a day. Like someone who is gradually staking his claim: 16.50 metres above deck, 18 metres overall. 4.20 metres wide. 2.50 metres deep. Almost 20 metres high. Every walk across the expansive deck aroused the boat builder's desires.

"And a dose of pity," admits Kalensee. You can ask, he thought, and called the owner. Could he take a look at the ship below deck? He could. Even on his own. What he then found inside the yacht would have made any sensible person turn round on their heels.

The "Doric" was not in good condition

"It all looked more like near-death to coma than Sleeping Beauty sleep." Meaning: A kiss was not enough. "A single building site," recalls Kalensee, describing a ghost train. "Totally grotty. I almost fell through the floorboards."

The cables hung like cabbage from the ceiling and out of shafts, all set up for 110 volts. "Dripstone hell, pigsty, greenhouse for all kinds of germs," summarises the man from the trade. Some of the seacocks only had an arm-length, cut-off hose on them. If you had come up against it, the ship would have sunk immediately - his biggest concern during the inspection.

Because I was alone on board, without the clamour of the vendors, I was able to take in the ship in peace. Even though everything was pretty warped, I liked the layout. Everything was well thought out." In the companionway, the entire service area was centrally located on two square metres. Galley, chart table and toilet: all within easy reach of the cockpit and with plenty of headroom. Then there was the spacious owner's cabin, navigator's or pilot's berth, the foredeck separated by a bulkhead. And above all the large, seaworthy cockpit.

Many construction sites on board the aluminium yacht

There was also a replacement Mercedes engine on the aluminium yacht, albeit on hard feet with a gear stick on the gearbox, not yet properly marinised. "If it had been put into operation like that," says Kalensee, "it would probably have shaken the ship to pieces." And even worse: on closer inspection, he discovered a strip of water on the side and puzzled - was it just the engine in its previous life or had the whole ship been under water up to the unsightly mark? But by then, the future owner was already a goner.

One of the privileges of youth is unreasonableness and the fact that dreams fly even higher than usual and can therefore override reason. Today, a good 15 years and several cruises later, he would think twice about such a liaison, the boat builder muses; back then it didn't scare him. "Besides, I had a lot more energy for such a project," Kalensee adds succinctly.

This was followed by a second call to the owner. The money and the crucial question were on the agenda. Kalensee wanted to find out whether a simple number would put an end to all the dreaming. In the end, no matter how determined, idealistic, expert, ambitious and all of the above you are, you can only capitulate in the face of some owners' asking prices. Or you bet on time. And that's exactly what happened.

The aluminium yacht became a restoration project

The "Doric" bobbed and twilighted in Rostock's museum harbour, completely deserted. One winter later, in 2005, Kalensee's phone suddenly rang and it was the owner. Did they want to meet up? They wanted to, of course. The deal was struck.

"From then on, every day was an adventure," says the new owner of the aluminium yacht "Doric", summing up the restoration. With the purchase contract came a lot of work. The first thing the new owner did was something you would never normally do on a yacht: he went over the deck with a high-pressure cleaner. "That," he says almost mischievously, "felt like it doubled the value of the boat on the very first day." It was also pleasing to see that all the winches were new.

The maiden voyage was in December 2005, "with black ice across the Baltic Sea to the North-East Sea Canal", without heating, of course; nevertheless a super trip. After final work in the saloon and the galley in the style of the sixties, the first season was sailed through in 2006, largely without any problems. This was followed by more positive than negative surprises. The proud owner was able to see for himself that the sailing characteristics of the "Doric" were beyond reproach. Despite its size, the ship was manoeuvrable because it was light. The gentle, banana-like crack in the deck and the voluminous overhangs provided buoyancy and allowed the ship to sail dry, as if built for dancing on the waves of the oceans. Despite the regatta ambitions of the first owner, the "Doric" is very comfortably equipped. And the Resopal pantry can probably be described as the unique selling point of this classic.

Tripp's design set standards

The designer Bill Tripp Jr. was one of the most celebrated yacht designers in the USA in the 1960s. Today, he has been forgotten - unjustly, as Kalensee believes. The man was passionate about his profession and knew what he was doing. As a pioneer of the first fibreglass constructions, he made a significant contribution to initiating a paradigm shift in boat building: reducing the cost of ships and increasing the popularity of sailing. Born on Long Island in 1920, he is said to have started drawing boats as a teenager. Tripp later spent two years as an apprentice to Philip Rhodes. After the outbreak of the Second World War, he served in the Offshore Patrol, which used private yachts to search for German submarines in the North Atlantic in winter.

After the end of the war, Bill Tripp continued his training at the second major design studio of those years: Sparkman & Stephens. In 1952, he finally set up his own business with Bill Campbell. Up to this point, his boats were all made of wood; fibreglass was still viewed with a great deal of suspicion. Tripp recognised the potential and began experimenting by subjecting laminate panels to the somewhat different moose test. If the panel under the tyres could withstand the weight of his Jaguar a few times, it had passed its first test!

The designer receives many orders

These and similar experiments gave him enough confidence in 1956 to realise plans for a 40-foot yawl made of GRP for a race under the CCA (Cruising Club of America) rules. The Block Island yacht was built. Just two years later, he was commissioned by the renowned Henry Hinckley Company from Maine to design a modified version of the Block Island. Tripp made a few improvements and the Bermuda 40 was born. A good 60 years later, these seaworthy cruising yachts are as popular as ever with blue-water sailors, still commanding higher prices than any other yacht of their age in their class. This layout is considered by many to be the most beautiful ship of the early fibreglass era.

But Tripp not only scored with ocean-going cruising yachts, he was also successful on the regatta courses. One of his early designs was a 48-foot slup with a flush deck, which was built by Abeking & Rasmussen. The boat, named "Touche", set a course record in the 184-mile race from Miami to Nassau, which made Tripp widely known and brought him many orders for new boats. In the course of his career, he became a real challenger to the decades-long dominance of Philip Rhodes and Olin Stephens. Tripp went on to design successful ocean racers for an established clientele and became chief designer at Columbia Yachts. His life ended abruptly and early. He died in 1971, aged just 51, when a drunk driver collided head-on with his Jaguar. His legacy is a long list of remarkably beautiful and seaworthy boats. The "Doric" is a sublime example of this - a true classic.

There is a lack of variety

Wolfgang Kalensee also shares this opinion. However, he usually distances himself from the local scene with his aluminium yacht "Doric"; it's not really his thing, he explains: "The colourfulness is gone compared to the first veteran regattas, when there were still fiddled boats with some hippies on them. Then you knew they were going sailing around the world again next week. Or at least give it a go, even if they only got as far as the Bay of Biscay. They didn't care. Today, it's largely the purse strings that have taken over the classic scene," regrets Kalensee. From his point of view as a boat builder, it is perhaps fair to add.

Some people invest time and expertise in their yacht, others invest money and inheritance. Unfortunately, love alone is often not enough. Otherwise, a ship like Tripp's most infamous design, which has been offered for sale in the Caribbean for years in vain, will end up like the former "Wappen von Bremen", which went down in the annals of yachting as the "Apollonia". A double murder took place on her during an Atlantic crossing, which can be read about in Klaus Hympendahl's "Logbook of Fear".

For the sake of completeness, it should also be mentioned that if you don't want to buy a potential ghost ship and prefer a modern Tripp, you can have a ship in the superyacht segment designed by Bill Tripp's son of the same name. Biographer Ted Jones writes about the son that he was too young at the time of his father's death to understand what had made his designs so special. And yet the son surpassed his father in his speciality.

Today, Bill Tripp designs maxis and mega yachts (for Baltic Yachts and Michael Schmidt Yachtbau in Greifswald, among others) that his father could never have dreamed of. Whether they have the potential to become classics, like the "Doric", the Bermuda 40, the Fastnet 45 by Lecomte, the Columbia 50, the "Ondine" or several other one-off designs by his father, remains to be seen.

This article first appeared in YACHT 25-26/2020 and has been revised for this online version.

Technical data "Doric"

- Shipyard: Abeking & Rasmussen

- Designer: Bill Tripp jr.

- Material: Aluminium

- Hull length: 16.50 m

- Waterline length: 11.00 m

- Width: 4.20 m

- Draught: 2.50 m

- Weight: 20.0 tonnes

- Sail area: 120 m²

- Engine: 88 hp