"Tarantella": Ur-Swan lays foundation stone for exceptional Nautor shipyard

Klaus Andrews

· 30.03.2025

She is one of those yachts that were able to set remarkable milestones in sailing history. As a GRP pioneer and the basis of the exceptional Nautor shipyard, the 36-foot "Tarantella" is one of the most important sailing boats of all time. No less.

More from the shipyard:

After all, the Nautor shipyard and its Swan brand have been synonymous with high-quality yachts for 59 years now. When the company was founded, it was anything but foreseeable that the factory in Pietarsaari, Finland, would be such a success story. The town council even refused to grant a plot of land due to the lack of prospects for success.

Turning away from traditional yacht building towards series production

The idea of building a shipyard for sailing yachts in the far north of the Gulf of Bothnia was the brainchild of 29-year-old Pekka Koskenkylä. He had studied economics, worked in the USA and sold paper sacks to the sugar industry on his return. It was probably a rather boring job, his dreams were on the water. He had built canoes as a schoolboy, but only discovered his interest in sailing after his studies. He spent two years building an eleven-metre sailing boat in his stepfather's barn in his spare time, but sold it to a dentist from Helsinki before it was launched. "I made a good living from it and thought that boatbuilding was an easy way to make money," he recalls at the shipyard's 50th anniversary celebrations in summer 2016.

His business plan was based on two ideas that seemed almost revolutionary at the time, given the conservative nature of sailing. Firstly, his boats were to be made of GRP, a new type of construction material made of glass fibre and polyester, which had previously been used more for building small motorboats. His idea of producing boats in series in order to rationalise production and save costs also marked a departure from traditional yacht building. Until then, money had not played a major role when buying a boat. Sea-going yachts were usually hand-built and therefore expensive. If you couldn't afford it, you just didn't buy it. Finished.

Design office Sparkman & Stephens draw Ur-Swan

There were already shipyards producing sailing yachts made of fibreglass-reinforced plastic. In Germany, Willi Asmus in Glückstadt on the River Elbe got into this new technology and delivered his first Hanseat 6.5 KR in 1964. Koskenkylä was working on a new strategy: he wanted to get as many hulls as possible out of the expensive negative moulds. This was because each additional mould number reduced production costs and increased profits. His budget was so tight in the early years that the founder initially even kept his job at the paper factory. In times of expensive long-distance calls, this was smart because he could use the office telephone, which his superiors naturally knew nothing about.

His decision to hire the design firm Sparkman & Stephens was a stroke of luck. The world's leading yacht designers at the time had not even responded to an initial enquiry from the nobody. It was only his telephone enquiry that led to a meeting with Rod Stephens in Helsinki. And finally, the New Yorkers released the plans for a 36-foot boat.

The plans for this first Swan were not yet an exclusive design for Nautor. Various shipyards around the world had already built 60 boats from wood according to these specifications. An S&S offer from 1967 explains: "The Swan 36 originates from the successful 'Hestia' from 1957. Two modified versions from 1964 sailed successful Baltic Sea regattas. In the 1965 One Ton Cup, two of these designs, 'Diana' and 'Hestia', took the first two places."

Production in Pietarsaari therefore started with a regatta-proven design that was also intended to appeal to normal leisure sailors. At the time, cruisers with a split lateral plan were considered radical, and the GRP version was three tonnes lighter than its glued sister ships.

Classic building materials steer away from Manufacturing material GRP from

The construction of GRP yachts required two cost-intensive steps. First of all, a precisely and cleanly crafted positive mould was required in order to remove the negative mould from it. Usually, the positive mould, disrespectfully called a "plug", has no further function and is destroyed after the moulding process. The Finnish newcomer could not afford to do this. So the first model was made conservatively from moulded mahogany and removed after moulding. It went to an owner who did not really trust the new material GRP. This Swan 36 with the construction number 000 is still sailing in Helsinki today.

Plastic yachts with a lot of visible white were considered unsellable at the time - too modern and not aft enough. Koskenkylä therefore had a lot of classic material used. The cockpit coaming, hatch frame and foot rail of the first Swans were made of wood, most of the fittings were made of bronze. One argument often used against GRP yachts was their supposedly short service life. At that time, it was not yet clear how the new material would behave. Production was based on the regulations of Lloyd's Register of Shipping. But even the experts from London could not predict how polyester would age. To be on the safe side, the Finns simply laminated it a little thicker, a method that is still used today to avoid precise calculations and the targeted use of materials.

Now the first Swan from shipyard founder Koskenkylä still had to be sold. The GRP pioneer was keen to sell it to a well-known sailor in order to gain a reputation. He had his sights set on Heinz Ramm-Schmidt, a successful regatta sailor who had just sold his 9.50 metre Viking cruiser. Easy prey, it seemed.

First Swan "Tarantella" goes on sale

50 years later, at the shipyard's anniversary celebrations in Turku, the now 96-year-old Ramm-Schmidt recalls with a smile: "The first time Pekka visited me was in Helsinki in December 1966. Without saying anything, he put some design drawings on my table. I looked at them for a long time. Finally Pekka asked: 'What do you think of your new yacht? But this was a one-tonner, I could hardly afford a boat that big. So Pekka left without my signature.

When I came home the day before Christmas, I found Koskenkylä in the kitchen, where he was charming my wife Ebba and the four children with the merits of his project. I read it off the happy faces of my family - they had already bought the boat, so to speak, without asking me." So he signed the contract; the Nautor shipyard was up and running.

The family then kept a close eye on what was happening on site, 500 kilometres north of Helsinki. "We travelled there several times to watch the construction, and a race developed between the first three owners. Everyone wanted to see their boat in the water first. In the spring, we parked a caravan on the nearby beach and checked the progress of construction every day," says Ramm-Schmidt, reliving those days.

The shipyard was unable to meet the planned deadline of 1 May. "We were ten weeks behind schedule. But have you ever heard of a boat that was finished in the promised time?" asks the old man rhetorically.

The launching took place on 15 July 1967. Before that, however, the transport from the shipyard shed to the harbour turned into a minor disaster. The journey took 15 kilometres along poorly constructed country roads. The transport came to a halt in an avenue of birch trees: The trees were far too narrow and the boat could not fit through them. The pragmatic Finns solved the problem with a chainsaw and quickly felled the row of trees on one side. Shortly afterwards, the trailer broke down and landed in a ditch. The village blacksmith forged a new axle for the trailer during the night and the caravan moved on.

Dramatic maiden voyage results in repairs

In the meantime, time was running out and the crane at Pietarsaari was no longer available. A quick decision was made to tow the boat to the port of Ykspihlaja near Kokkola, a diversion of 40 kilometres. The Ramm-Schmidt family spent a sleepless night, but the next morning their boat was bobbing in the water. But "Tarantella" wasn't even finished yet. The craftsmen only screwed on the remaining fittings during the transfer to Pietarsaari. "There was already a band on the pier and some of the townspeople were watching the spectacle," recalls the owner at the time. "Finally, we poured a bottle of champagne over the bow and all the important fittings."

At four o'clock in the afternoon, a fanfare band blew to set sail. "We didn't even have our things on board yet, but they wouldn't stop playing," laughs the old man. So they cast off in a strong westerly wind and soon realised that the fittings were fastened with screws that were too short.

Ramm-Schmidt describes this maiden voyage from Pietarsaari to Helsinki as "dramatic". "The first thing to come loose was the boom, then the expensive wind measuring system hung down from the mast, and even a genoa rail came loose from the deck."

After successful repairs, the boat took part in many regattas for two years and the family went on holiday trips around the Baltic Sea. "Cruising was a must!" the old man confirms the demands of his wife and children. Rod Stephens also accompanied them several times to gather impressions and ideas. Thanks to his suggestions, the shipyard got all the teething troubles under control. In the end, the Stephens brothers were convinced of the quality of the first Swan and from then on supplied the shipyard with exclusive designs.

When Ramm-Schmidt brought the boat to the shipyard for its third winter storage in 1969, the boss thanked him with a generous proposal: "Sell the boat and you'll get a new Swan 37 in return." This was the shipyard's second model. So they sold "Tarantella". The "Tarantella 2" traded in for it is still owned by the family after 47 years.

"Tarantella" shines for the shipyard's anniversary

34 years later, Nautor's archetype was up for sale a second time, and the shipyard took it on itself. On 17 December 2003, a semi-trailer brought the Ur-Swan back to Pietarsaari from the Swedish island of Orust. After an extensive refit, she now advertises the brand as a floating museum.

For the 50th anniversary of Nautor in 2016, "Tarantella" was to shine once again. Two men who had been involved in the construction of the boat in 1967, including the first Nautor employee, 78-year-old Jan-Erik Nyfelt, even got involved. Having long since retired, the old men came to the shipyard once a week to make the boat beautiful again. They then sailed "their" boat in person in the anniversary regattas off Turku and Sardinia.

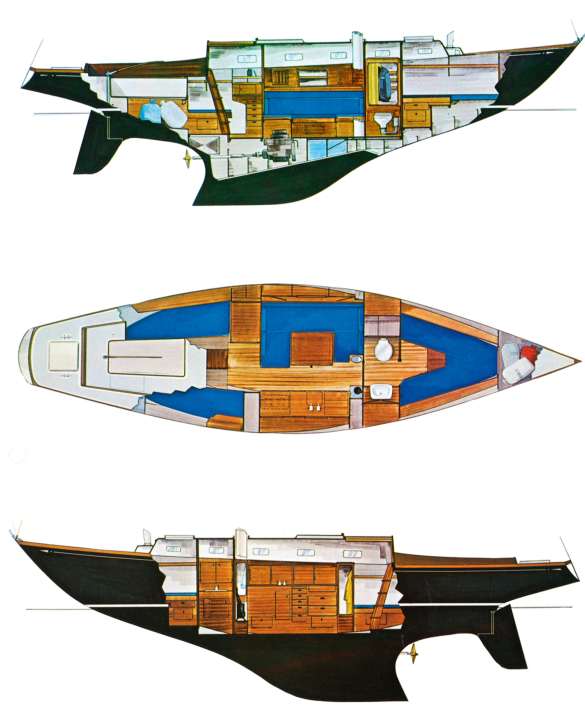

At first glance, it looks exactly the same as in the old brochure with its classic lines and aesthetically pleasing deck. The details that reflect the state of the art of the time are exciting. The deck still bears the typical diamond pattern of the anti-slip structure, as seen on many yachts. The positions of the deflection blocks and bronze fastening eyes remained smooth; they had already been precisely defined on the drawing board and fixed in the negative mould. The 120 centimetre long genoa rails are recessed into the deck.

Shape is a feast for the eyes, sailing a pleasure

Sparkman & Stephens earned their reputation with radical yachts that were successful on the race courses. When it came to detailed solutions, however, they focussed on experience and evolution. "Tarantella", with its wide rounded pulpit, two dorade fans and the arrangement of the traveller and mainsheet guide, is part of this construction kit, which the Stephens brothers developed and refined further and further in practical use. Almost all S&S designs are equipped with these system solutions. At the time, trade journals praised the extremely spacious boat with sleeping space for seven people. Compared to current designs, the spaciousness seems almost intimate.

The large deck and low hull are a feast for the eyes. Despite her low freeboard, "Tarantella" sails very dry. On the cross, she quickly lays down on the forecastle and forms a deep wave trough in which the boat does not accelerate significantly above hull speed. At cockpit level, the freeboard shrinks to a few centimetres. The wheel is tiny by today's standards. In the narrow cockpit, the helmsman can hold on to the railing with one hand while easily steering with the other.

The first Nautor yacht is now an icon. As the first product of her shipyard, today she creates identity and connects owners of boats between 36 and now 131 feet. Thousands of spectators wave after her at the departure parade in Turku to celebrate her anniversary. A small yacht and five old men in striped jumpers and black caps.

Technical data of the Swan 36 "Tarantella"

- Designer: S & S

- Production time: 1967-1970

- Torso length: 10,91 m

- Width: 2,94 m

- Depth: 1,90 m

- Weight: 7,0 t

- Ballast/proportion: 3,6 t/51,4 %

- Mainsail: 21,3 m²

- Genoa (150 %): 42,0 m²

- Spinnaker: 101 m²

- Machine: Volvo P., 15 hp/11 kW

The article was first published in 2017 and has been revised for this online version.