- Scalar 40 is the longest-serving ocean-going series yacht in Germany

- The look and flair of the wooden deck is unique

- Sophisticated keel suspension on the Scalar 40

- Practical and beautiful details even in the companionway

- Control by tiller - how beautiful!

- Old school, modern components

- Technical data Scalar 40

The German series shipyard scene is extensive and diverse. In addition to global players such as Hansegroup and Bavaria Yachtbau, which together with the Beneteau Group and the French consortium of Dufour and Fountaine Pajot are among the four largest shipyards, smaller, specialised companies such as Sirius and Bicker contribute to the diversity of the industry. One particular highlight is Henningsen & Steckmest, an established jewel in the shipyard landscape. Founded in 1958 in Kappeln-Grauhöft on the idyllic Schlei, a team of over a dozen boat builders, carpenters and locksmiths has been producing the Scalar series since 1973, in addition to a number of customised products such as the "Gaudeamus".

The robust, high-quality and seaworthy Scalar yachts, which were designed decades ago by Rolf Steckmest, the senior partner, only occasionally receive orders. In fact, there are years in which no new boat is launched in Grauhöft. However, the brothers Hauke and Malte Steckmest, the third-generation managers, are fully occupied with customer service, winter storage, conversions, refits and harbour operations.

Scalar 40 is the longest-serving ocean-going series yacht in Germany

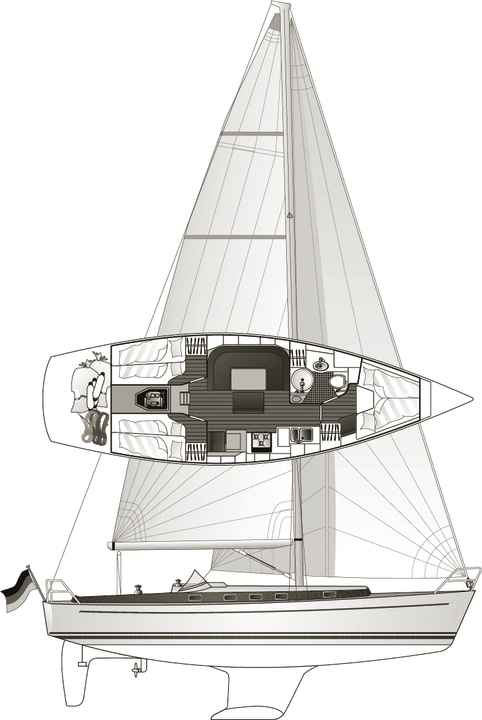

Nevertheless, new builds remain the boatbuilding challenge, the drive: "You can't do without them." The small series programme, whose name is tellingly derived from an ornamental fish from South America known as a sailfin, essentially consists of the 34, which was last launched in 2018, and the flagship, the Scalar 40. Although Georg Nissen's design is the youngest ship in the fleet, it is also 18 years old. And only construction number 4 of this type is currently underway. This makes the Scalar 40 the longest-serving ocean-going series yacht in Germany.

They need their time on the Schlei, and they take it. Boats seem to mature there like an expensive single malt in a Scottish family distillery. The flagship devours around 3,000 hours of labour just for the elaborate deck, for example, while a Hanse of the same size is built in just under 700 hours - complete. The deck and cockpit are the Scalar's most unique selling point, made entirely from wood in the traditional way (see below), from mahogany, abachi, teak and marine plywood. The labour hours required for a Scalar 40 can only be compared with those of other shipyards to a limited extent.

The vertical range of manufacture at Henningsen & Steckmest is enormous. No prefabricated timber is delivered here, but whole tree trunks. Starting with the cut plank or veneer sheet, they produce a wide range of blanks for the deck beams, superstructure sides, superstructure forepart, beam walkers, slings, cockpit roundings and walls, coaming and more. The blanks are then finely machined, roundings are milled, bevelled edges and hinges are attached. All the parts have to be fitted and stretched until everything fits. Hauke Steckmest: "And that's the same for every new build!" A wooden deck is a non-reproducible one-off, not a series production, says the co-head.

The look and flair of the wooden deck is unique

The work carried out by highly qualified specialists in large numbers of hours is reflected in the price: a Scalar 40 costs from 550,000 euros today, more than double the price of a mass-produced yacht of the same size. And this is despite the fact that the wooden deck "offers no real functional advantage", says Steckmest. But the traditional look, the flair, that cannot be achieved with plastic, would be confirmed by any of the owners, who are unanimously delighted with the individual soul of their yachts.

Another advantage of the shipyard that is appreciated and utilised by the owners is the possibility of individual adjustments, where even the bulkheads can be moved by up to ten centimetres. This allows for larger berths, longer saloon sofas or more voluminous wet cells. The superstructure windows can be positioned individually as required, a small technical advantage of the timber construction method, whereas the installation positions are usually fixed for standard decks and can only be modified at great expense using a reprogrammed milling machine and other measures. Customised construction means more than just larger or smaller berths, aft large forecastle boxes are possible instead of berths or, as in the case of construction number 3, bunk beds instead of double berths. And, of course, different types of wood and fittings or on-board technology. Just as examples.

Sophisticated keel suspension on the Scalar 40

They also build the hulls themselves. They are hand-laminated with isophthalic acid resin in the outer layers, made of solid material in the underwater area and as a sandwich construction on top. In keeping with traditional design, the fin keel is bolted to a stub stepped aft. This, which harmoniously completes the curve of the S-frame, features a bilge well, as is familiar from wooden classics. The boat builders from the Schlei also pay great attention to the keel suspension with very large shims for the keel bolts, a strong construction of the floor cradles, which are anchored in the hull on both sides with pronounced angle laminates, and bulkheads, which are also fixed on both sides with angle laminates.

But it is always the woodwork that particularly characterises Henningsen & Steckmest. The 12-millimetre-thick plywood deck is covered with 10-millimetre-thick teak rods, which have a joint depth of the full plank thickness, ensuring a long service life as the deck can be sanded several times and thus refitted. The deck surface is finished with a wooden toe rail and is drained via several drainage hoses that exit just above the waterline, which prevents unsightly rain streaks on the outer skin.

Practical and beautiful details even in the companionway

It is clear that so much love for craftsmanship, practical solutions and traditional boatbuilding features does not stop at the decline. The khaya mahogany fittings are made using classic frame production; cupboard fronts and doors are solid or made with a foam core in a weight-saving sandwich construction, and sash mouldings on tables or worktops and some edgings are laminated. The perfect craftsmanship and precision are matched by the retention of tried-and-tested features that originate from practical experience but are sometimes lost in modern series production. This starts with the aforementioned bilge, then the backrests of the saloon berths can be folded up to create wider berths. Open locker compartments have removable scupper rails. The door frames are protected in the step area by stainless steel plates, and the side walls are fitted with air-conditioning and attractive weather strips. A box with spare parts and tools is securely stored in the engine compartment.

And the feasible individuality continues into the cupboards: their interior fittings and dimensions are adapted to the owner's crockery and glasses. It almost goes without saying that the tanks are made of stainless steel or, in the case of the water tank, are made of GRP and integrated into the hull with a positive fit, the service batteries have 300 amp hours and a heater comes as standard.

The beautiful details continue on deck, consistently and thoughtfully. The laminated, 1.30 metre long tiller ends in a 24-edged geometric body, a so-called cuboctahedron - looks good and is easy to grip. Wheel steering is of course possible instead of a tiller. Surrounded by a high coaming (with swallow's nests, hurrah!), the dikes are a generous 2.60 metres long. The engine can be accessed from above via a hatch in the cockpit floor. The forecastle box is custom-made, the lid accommodates the bulkheads, shelves are standardised Euro stacking containers (these are the grey ones that are available in many places). The bow thruster can be operated with foot pedals, as you want to be able to see what's happening at the front while standing. The woodwork: a feast for the eyes and hands. The components: top shelf. The instruments: easy to read and operate on the companionway.

Control by tiller - how beautiful!

Oh yes: she also sails. And how. Thanks to the rather long keel and the large, skeg-guided rudder blade, she tracks faithfully. She also quickly scratches the seven knots at the cross, manages small turning angles, is agile in manoeuvres and reacts willingly. Provided the sails are well trimmed, she can take revenge for negligence with more rudder pressure than is conducive to performance, which is quickly felt with the tiller. Yes, the tiller, why is it so rare? Less expensive to install, less maintenance and less potential for problems, a direct steering feel, also easy to steer from the edge using the outrigger, and on top of that, the rudder stock gives the helmsman a wide range of action in the cockpit, as the Scalar proves wonderfully.

She is not a lightweight, which is also noticeable. However, the 9.3 tonnes of weight are offset by 93 square metres of sail area when the 135 percent genoa is selected. This means a high sail carrying capacity of 4.6, which classifies the Scalar 40 as a very sporty boat. Other key figures indicate a great deal of stability: 37 per cent ballast and a draught of 2.10 metres are solid values. And it's beautiful too: with the slight deck step, the moderate yacht stern, the flat superstructure and the sloping stem, it was timelessly beautiful almost 20 years ago and still is today. She may lack modern achievements such as maximised interior space, a huge cockpit and a bathing platform. Instead, she is a modern classic, more wooden yacht than GRP vessel - customisable and of higher quality than almost any other series-produced yacht.

Old school, modern components

Only very few shipyards produce GRP hulls with wooden decks in series production. In addition to Henningsen & Steckmest, there are two other German shipyards: Bootswerft Funger in Kempen and Bootswerft Bicker in Ahlen. In Kappeln, boat builders screw, bolt and glue the notched deck beams under the wide hull flange. The plywood deck is glued onto the braced deck beams with epoxy. The side walls of the superstructure are laminated in three layers of mahogany, with 10 millimetre thick longitudinal layers on the inside and outside and a 2.5 millimetre thick transverse layer with vertical grain in between.

The outer layers of the superstructure and the coaming are made of continuous wood. The sides of the superstructure are screwed to the plywood layer from below and glued on with epoxy resin. The plywood surfaces are covered with teak. A two-layer plywood deck is glued onto the deck beams of the superstructure, which are clipped into the superstructure and the beam traveller. The deck is then coated with fabric and epoxy and varnished. The production follows traditional boatbuilding techniques, but uses the perfect adhesive in the form of epoxy and a modern process in the form of gluing.

Technical data Scalar 40

- Design engineer: Georg Nissen

- Torso length: 11,99 m

- Waterline length: 10,52 m

- Width: 3,70 m

- Depth: 2,10 m

- Weight: 9,3 t

- Ballast/proportion: 3,5 t/37 %

- Mainsail: 45,0 m2

- Furling genoa (Genoa III): 38,5 m²

- Sail carrying capacity: 4,3

- Engine (Volvo Penta): 53 PS

Further information at scalaryachts.com

More on the topic:

Fridtjof Gunkel

Deputy Chief Editor YACHT