The afternoon of 10 August 1628 is summery and balmy as the new pride of the Swedish fleet sets off on its maiden voyage. Numerous onlookers have gathered on the quay below the castle, the three masts of the galleon rise majestically into the Stockholm sky. Only three of the ten sails are set. Accordingly, the "Vasa" drifts slowly away and towards its destination for the day, the island of Vaxholm, just a few nautical miles away. But after a few minutes, a gust catches the Swedish navy's largest and most powerful ship to date and causes it to heel precariously to port.

The "Vasa" only managed 1,300 metres, then sank

Another gust of wind from the south follows. Water shoots through the ports and fills the lower battery deck. Loose pieces roll aft, the cannons start to slide. The mighty warship is pulled inexorably into the depths, not having travelled a single nautical mile on its maiden voyage. Around 30 people are trapped below deck by the water, the others can be rescued by dinghies rushing to the scene. It is too late for the ship itself - it sinks to the bottom of Stockholm harbour, until only the topsides protrude warningly above the waves.

Today, almost 400 years later, the galleon can be found on fridge magnets, pillboxes, napkin rings, tea towels, T-shirts and as a model kit. Around 1.5 million visitors flock to the Vasa Museum near the large marina named after her on the royal island of Djurgården every year. And the number is growing. The former disaster of the failed prestige project has become a commercial success story.

This is thanks to Anders Franzén, a young naval technician and amateur archaeologist, who endeavoured to locate sunken warships from the 16th and 17th centuries with the help of archive material in the early 1950s. He spent almost two years searching for the wreck, which he initially wrongly assumed to be on the southern side of the fairway. In addition, the galleon was largely buried under rocks from blasting work carried out at the beginning of the 19th century for the construction of new quays.

It was not until the autumn of 1955 that Franzén received the decisive clue. An undefined elevation 120 metres off the island of Beckholmen was marked on newly created sounding maps for a planned bridge construction. On 25 August 1956, the time had finally come: Franzén's plumb bob unearthed a piece of black oak - the "Vasa" had been found.

Salvage of the "Vasa" lengthy and not a matter of course

It was not a foregone conclusion that the discovery would be followed by a salvage operation. But Franzén managed to convince the relevant authorities that an almost completely preserved warship from Sweden's days as a great power would not only enrich the country's cultural heritage, but would also be a magnet for visitors from all over the world. It was another five years before the "Vasa" could return to the surface.

Today, nobody knows the ship as well as the American Fred Hocker. When he first saw the light of day in 1961, the galleon was in its second season. Hocker has since dedicated 15 years of his life to her. He started out as a wooden boat builder at a shipyard in New England before studying medieval history and maritime archaeology and eventually becoming an associate professor. In 1999, he moved from Texas to Denmark to work at the National Museum in Roskilde. From there he was headhunted to Stockholm four years later to research the past of the "Vasa".

In the long term, however, the bigger question will be whether the will to preserve the ship survives"

Fred Hocker, "Vasa" researcher

Recently, Hocker had a discussion with the first and so far only Swedish astronaut Christer Fuglesang about which of the two had the better job. "In the end, he had to admit that it was me. While Christer has to train for years to get closer to his research object for a few weeks, I have it right in front of me every day." Over the years, this closeness has meant that even the smallest details about the ship, its crew and the historical background are now known.

"Vasa" part of the Swedish armament programme

The man who commissioned the "Vasa", Gustav II Adolf of Sweden, helped his country to become a great power. Sweden had been repeatedly involved in wars over maritime trade routes since the middle of the 16th century. At the time of "Vasa", Finland was part of Sweden; Estonia and most of today's Latvia were in Swedish hands. The king's enemies were not only Russia and Denmark, which had long been rivals for supremacy. In addition, the Polish King Sigismund was a cousin of Gustav II and laid claim to the Swedish throne; the Swedes had always feared Catholic influence from Poland.

The principle of forward defence was therefore proclaimed as early as the beginning of the 17th century and a comprehensive rearmament of the fleet was undertaken in the 1620s. But more ships alone were not enough for the king. In 1624, he ordered the construction of a completely new type of galleon with two battery decks and much heavier cannons.

The Stockholm shipyard was the largest employer in the country at the time; around 500 people of various nationalities were employed there. Most of the carpenters came from the Netherlands and built the galleon using the tried and tested method from their home country. Instead of first positioning the frames and pulling up the outer skin on this scaffolding, the planks were first provisionally joined together, resulting in the shape of the hull.

Missing stability calculations

The two tenants of the shipyard, Henrik Hybertsson and Arendt de Groot, were also Dutch. While Hybertsson was responsible for building the ships, de Groot travelled the country and bought the necessary materials. But they soon ran out of money. The introduction of the copper coin in 1624 led to a sharp fall in the currency, which in turn caused the workers to go on strike because their wages were too low. This not only delayed the completion of the ship - the king's prestige object also became a loss-making business for the leaseholders. The cost of the hull alone was 27 per cent over budget. Meanwhile, Hybertsson fell seriously ill and died in the spring of 1627, to be succeeded by Hein Jakobsson.

It was not only the design that was new, but also the amount of artillery on board. The king ordered his latest warship to be equipped with 48 new 24-pound bronze cannons. Never before had so much firepower been concentrated on a single ship. This meant that two battery decks were needed instead of one, the lower of which had to be much closer to the waterline than usual. However, the main problem was that the galleon's centre of gravity shifted upwards. Mathematical formulae for calculating the stability of a hull were still more than a hundred years in the future, and knowledge of the relationship between construction and seaworthiness was rudimentary.

Nowadays we know that the wooden construction itself was too strong. The beams of the battery decks were unnecessarily massive, the ceilings too high. The problem could not have been solved by adding more ballast to the hull, as had already been discussed in the 17th century; this would have merely placed the "Vasa" lower in the water. The only promising solution would have been to clear the upper battery deck - which was not possible for military reasons.

Deceased designer becomes a scapegoat

The instability of the ship was well known to those in charge. In the spring of 1628, when the new pride of the fleet was already in the water, Captain Söfring Hansson exposed the shortcomings to Admiral Klas Fleming by having 30 men repeatedly run from one side of the deck to the other. The demonstration had to be cancelled because the ship was swaying too much. However, Fleming decided to keep the information to himself and not inform the king of the dubious seaworthiness of his new prestige project. Disaster was inevitable.

Hansson was arrested immediately after the sinking, but the actual interrogations did not take place until a month after the accident. This gave everyone involved time to come up with their version of the story. It was quickly agreed that it was a design fault. The master shipbuilders testified that they had built the galleon according to the measurements given to them by King Gustav. The trial thus became a political spectacle to find someone to blame. The opportunity arose when Hein Jakobsson testified that his deceased predecessor Hybertsson had possibly made a mistake. As he was no longer able to defend himself, he proved to be the ideal scapegoat. Although it was clear that the key people had recognised the problem long before the departure, no one else was found guilty. Most kept their positions and continued their careers in the navy.

333 years under water

The sister ship "Äpplet" was in service for almost 30 years. Almost all of its dimensions were similar to those of the "Vasa", its length, its draught, even the number of cannons. The decisive difference was that she was three feet and seven thumbs wider, i.e. 1.07 metres. This resulted in around 100 tonnes more displacement and correspondingly more space for ballast. Hein Jakobsson had made these changes before he realised that there were problems with the "Vasa". The "Äpplet" was already in the water on its maiden voyage.

A long sleep began for the "Vasa". Although salvage privileges were granted three days after the accident, the ship could only be righted. Attempts to raise the warship with the help of two pontoons failed - the galleon was already too deep in the mud. In the autumn, the decision was made to cut off the Mars sterns protruding above the surface of the water.

The fact that the "Vasa" survived all these centuries in the sea was mainly due to the special composition of Stockholm's harbour water. It was almost anaerobic, acid-free and heavily contaminated until the 20th century. Chemical processes took place very slowly and bacteria that contributed to decomposition could not survive. While the wood remained almost intact, all metal parts dissolved almost completely. Of the more than 600 cannonballs originally weighing 24 pounds that were found on board after salvage, most weighed less than half their original weight.

Scientists reconstruct the situation at the time

Finds such as 15 preserved skeletons and the abundance of belongings provided the first insights into the period. Fred Hocker's appointment in 2003 created the first full-time position for research into the "Vasa". Most of the investigations are carried out by the team of seven scientists on the ship itself, but for some of the findings they have had to leave their familiar surroundings.

Intensive study of the wreck provided the first clues as to how the galleon was sailed, but many questions remained unanswered. The replica of the "Kalmar Nyckel", an armed merchant ship that transported the first Swedish settlers to America in the 17th century, provided more information. Hocker describes it as a small-scale "Vasa" with a similar rig and steering system. The ship was made available to the museum's researchers for three summers. "The experience we were able to gain in this way could not have been replaced by any literature." It turned out that the galleon got most of its propulsion from the foremast and the mainmast. However, the mainsail was rarely set, as it largely covered the jib and blocked the view - it was not used once on the "Vasa".

Vasa Museum shows the original

Sailing in bygone eras, maritime history, a marine archaeological masterpiece: a visit to the "Vasa" is almost obligatory for visitors to Stockholm travelling on their own boat. Ideally, they should moor in the marina right next to the museum. It is cool inside and the smell of old wood fills the air. The impressive exhibit fills the length of the large, open space. At the front, the huge bowsprit almost seems to hit the wall, while the visitor galleries run close to the stern. On five floors, visitors can not only view the galleon from all sides and see a selection of the numerous artefacts up close, but also walk through reconstructed cabins and learn a lot about how the crew members lived together.

Below, at keel height, the skeletons of the 15 crew members are displayed in glass cabinets. Based on the skulls, it was possible to reconstruct some of their faces. The clothing provided information about their role on board. Today, they face the visitor as wax figures and succeed in making the shipwreck comprehensible by means of individual fates.

In the dim light of the ceiling lamps, the hull shines as if it had been coated with wax. 98 per cent of the wood is original from 1628, only the planks of the upper deck, parts of the bowsprit and the rigging had to be replaced. If Fred Hocker has his way, the "Vasa" will survive the next millennium. This year, the ship will be given a new support structure that will better absorb its unevenly distributed weight. Then the "Vasa" will also be equipped for the next centuries.

The "Vasa"

The name of the ship refers to one of the regalia of the time: a vasa was a bundle of branches used by soldiers to protect themselves in enemy territory. The "Vasa" was to be one of four so-called insignia ships; its successors were called the "Apple", "Sceptre" and "Crown". Vasa was also the name of the noble family to which King Gustav II belonged. The word originally began with a "W"; it was not until 1989 that both the ship and the museum were spelt with a "V".

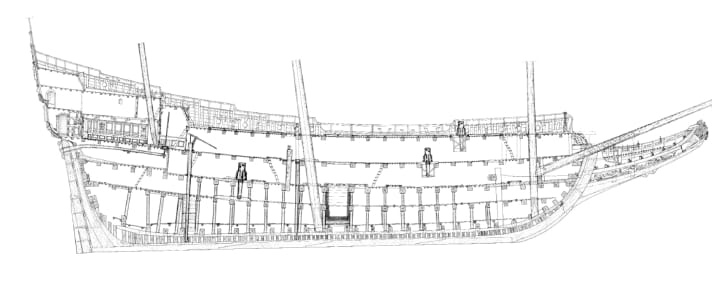

- Hull length: 69.0 m

- Height: 52.0 m

- Width: 11.7 m

- Draught: 4.8 m

- Sail area: 1,275 m²

- Displacement: 1,210 tonnes

The salvage

The "Vasa", which sank in 1628, was rediscovered in 1956 and salvaged until 1961

For the salvage operation, two pontoons floating on the water surface on either side of the wreck were first filled with water and lowered by a few metres. Ropes attached to them, which led down to the ship and were tensioned, were to pull the "Vasa" upwards with the buoyancy when the pontoons were pumped empty. In order to lead the steel cables under the "Vasa", divers had to dig six tunnels with high-pressure hoses for more than two years.

It was not until August 1959 that the actual salvage work could begin. The two pontoons "Odin" and "Frigg", named after the highest pair of Norse gods and equipped with a lifting capacity of 1,200 tonnes, carried out 18 lifts within four weeks. With each empty pumping operation, the Vasa gained around one metre in height and was towed into correspondingly shallower water. She finally remained at the bottom in a sheltered spot off the island of Kastellholmen for another year and a half. Thousands of metal bolts in the hull had disintegrated over the centuries and had to be replaced with wooden plugs.

Hybrid construction

As a result of the restoration, the "Vasa" is made of wood and plastic - and is therefore virtually ultra-modern

After she was salvaged, the "Vasa" was freed from the metre-thick mud and permanently sprayed with cold water to prevent the wood from drying out and deforming. The project management also bought up almost all the old bathtubs available in Stockholm, which were used to store figures and other parts of the ship. To combat bacterial infestation and rust, a solution of water and polyethylene glycol was sprayed over the "Vasa", initially manually and from 1962 via an automatic sprinkler system; the system was in use without interruption for 17 years. When the museum was opened above a naval dry dock in 1990, the air conditioning system was further developed and sensors were fitted to the hull. Since 2003, the movements in the ship have also been measured. This is because the "Vasa" is not only still drying out, but is also leaning further and further to port due to its unevenly distributed weight - just as it did when it sank in 1628.

Lying tip

If you come to Stockholm by sailing boat, you can join the forest of masts:

Wasahamnen Marina is located directly in front of the museum. In the high season from mid-May to mid-September, an overnight stay costs 350 Swedish kronor (approx. 35 euros, as of 2018) for boats up to twelve metres and 650 Swedish kronor (approx. 65 euros, as of 2018) for boats over twelve metres. This includes the use of showers, toilets, washing machines and unlimited internet access - as well as an unbeatable location in one of the world's most beautiful metropolises.

Wreck of sister ship discovered

Swedish archaeologists discovered a huge shipwreck from the 17th century in 2022. The research revealed that it was the "Äpplet", the sister ship of the "Vasa". Although the "Äpplet" lasted a little longer, it did not prove successful in the long term either. The ship was launched in 1629 and was declared unseaworthy in December 1658. The following year, the "Äpplet" was sunk near Vaxholm in order to block the strait to protect it from enemies.