- The trip to Kaliningrad was a long-cherished dream

- Beautiful Hel Peninsula

- Through a new lock onto the lagoon

- Magical light and sufficient depth on the Vistula Lagoon

- Entry to Kaliningrad past Pillau and military ships

- We are not prepared for sailing tourists

- Getting to the Kaliningrad Yacht Club is complicated

- People are looking for common ground

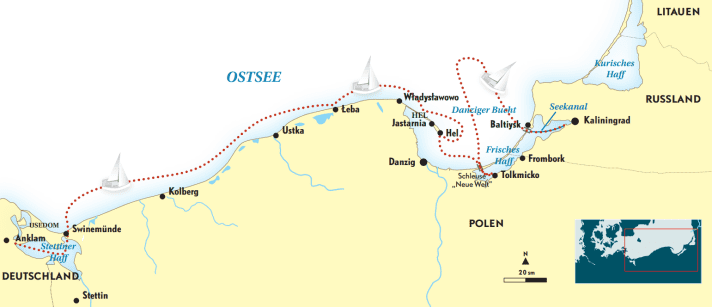

Soaking wet, the spinnaker sinks down through the forward hatch. I've done it! I recovered the cloth too late and let myself be softened by the swaying of the downwind! Until "Raukar" ran out of the rudder. Now, only under main and jib, she is back on course, heading eastwards under windvane control.

I'm sailing parallel to the Polish coast and am now roughly level with the town of Ustka. Down at the chart table, I enter my position on the nautical chart. And look for a harbour that I can call at. I've been travelling for too long. To be precise: a day and a half ago, I cast off the lines of my aged Sparkman & Stephens 30 in my home harbour, the Peene Yacht Club in Anklam. Since then, it has been travelling at a good speed, up to six and a half knots.

Łeba would be a good place to finally catch up on some sleep. But it's already getting dark and the wind has picked up to a good 5 Beaufort. However, I read in the coastal handbook that from 5 Beaufort upwards, dangerous bottom seas form off Łeba and small ships run the risk of capsizing. The water off the coast here is only four metres deep. Nevertheless, I decide to give it a try, grab the tiller, take the boom amidships and jibe towards the pier lights. It is now pitch dark.

The trip to Kaliningrad was a long-cherished dream

What am I actually doing here all alone? I could be out on a dinghy with my son or visiting a few people for a barbecue. Instead, I'm travelling to Kaliningrad. It's a long-cherished dream that will come true this summer of 2023. I have family there. Better: my wife has family there. She was born in the Russian exclave and her parents and siblings live in the city. Kind-hearted people who I appreciate and admire.

For example, my brother-in-law Nikolaj, who repairs chainsaws and is always in a good mood. Or my mother-in-law Olga, who still teaches higher maths as a pensioner. In the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, she had to sew clothes, sell clothes at markets or renovate the floor of a residential home with her children in order to feed the family. I also like Uncle Yevgeny, who drives the fastest Ford Fiesta in town with only one eye.

Yes, I can even get excited about Kaliningrad itself. Despite its angularity and a certain Soviet charm. The city is dynamic, simply great if you get involved with it. But now, in times of war, do I even have a chance of being allowed to enter the country? I don't know.

A bumpy start to the cruise

The sea becomes increasingly choppy. The pier lights of Łeba are now dancing wildly before my eyes. This can't go well! I am abruptly torn from my thoughts, a sudden realisation takes hold of me and without hesitation, I head back into the darkness of the open Baltic Sea. I'd rather go a little further than be thrown roughly onto the beach by the surging sea.

Around one o'clock in the morning, I turn round at a safe distance from the coast to make myself something to eat. Then I snuggle up in the leeward sail of the saloon berth and close my eyes. I wake up every 20 minutes, check my position and the sea around me and lie down again. Until half past five in the morning.

A cold wind greets me on deck. I'm already looking forward to the Hel Peninsula. I will soon have rounded the northernmost point of Poland, then I can drop off to the south-east and sail on into land cover. But "Raukar" is still bucking to port towards Władisławowo. Shortly afterwards, however, the high shore at Cape Rozewie becomes visible. "Wow, it's beautiful here!" I exclaim. I am magically drawn to the lee of the cape. I drop anchor a little east of the beacon.

Other single-handed sailors are also drawn to Kaliningrad

I've just brushed my teeth and there are already two more boats here, even German ones! My pent-up need to talk pushes me onto the swim ladder and I swim towards the nearest yacht. A short time later, I'm already on board with my neighbour at anchor. Also a single-handed sailor, but from further away than me. He comes from Eckernförde, has already been to the Vistula Lagoon and is already on his way back. So my plan doesn't seem so far-fetched if others have a similar idea.

The journey continues. Unfortunately, it's blowing out of the Putziger Wiek like there's no tomorrow. It catches me cold as I sail out of the lee of the Hel peninsula. Swallows play around in the rigging and try to cling on. The wind pushes strongly towards the harbour entrance of Hel. Shortly afterwards I'm moored at the jetty.

It took me 60 hours to get here from Anklam. I'm standing on shaky legs on land when the harbour master comes by. "You speak good Polish!" the friendly man tells me. I'm completely flabbergasted, as I tend to communicate with my hands and feet, mixing Polish with German or English without hesitation.

Beautiful Hel Peninsula

I landed in Hel, this pretty, albeit touristy fishing village, with an overheated engine. The seawater hose from the wet exhaust had flown off. After getting to know the village halfway in search of a garage, I get the coolant I need to finally get the bike running again.

Hel has a charming town centre with a beautiful church, in whose garden old fishing boats are moored. The peninsula of the same name stretches 20 nautical miles south-east into the Bay of Gdansk with the finest sandy beach.

I'm only 25 nautical miles away from my next destination, the new Nowy Swiat lock, which I want to use to cross the 70-kilometre-long but only a few hundred-metre-wide Vistula Spit to reach the lagoon behind it, or a day's sailing on the beautiful Bay of Gdansk. The only catch: the lock is not yet listed in my documents.

Through a new lock onto the lagoon

That's how I meet Pawel, the skipper of a charter yacht. While his crew are clearing the boat, I ask him about the approach to the passage, which will only open in 2022. He enthusiastically explains everything I need to know. His willingness to help is overwhelming. Pawel and I stay in touch for a long time. Even days later, he keeps asking about the progress of my journey via WhatsApp.

The next day we set off. I cross the entire bay in a light breeze. On the way, a seal even sticks its head out of the water. Then I'm at the gateway to the "New World", which is the translation of the lock's name. The facility in the south-east of Gdansk Bay welcomes me in the twilight. The sea reflects the light of the clear evening sky. Pier heads as large as sea-going vessels tower imposingly into the calm of the Baltic Sea. The structure is enormous. Nature all around.

Nowy Swiat cuts through the Vistula Spit over a length of one kilometre. Since last spring, sailing yachts have been able to enter the protected inland area east of Gdansk with a standing mast.

But I'm still in the outer harbour of the lock, the size of three bus stations. There's nobody to be seen. But I'm still excited. I passed through the last locks as a child in a folding boat on the Mecklenburg lakes. Communication here is by radio. I get friendly contact with the lock captain on channel 68. Where from and where to, the dimensions of the boat, how many people are on board? The man speaks very good English.

Magical light and sufficient depth on the Vistula Lagoon

Perhaps I should get rid of all my questions about the harbours in the Vistula Lagoon right here. So I put the man's friendliness to the test and ask for the telephone numbers of the harbour masters in Frombork and Tolkmicko.

Then the gates open and before me lies the long stretch of water that stretches from Poland all the way to Kaliningrad. Fascinated, I reach for the radio again, say thank you and congratulate the lock captain on this magnificent structure.

Magical light bathes the area in an almost mystical atmosphere, and on the opposite shore I can admire the gently undulating Elbe highlands through my binoculars. Shortly afterwards, I spot a whole row of other boats. "No way, they're sailing around here in real keelboats," I think as the first ones approach within shouting distance. "Two metres draft!" shouts a ten-metre yacht in response to my question about its draft.

The coastal handbook recommends that boats with a draught of more than 1.5 metres should not sail on the Vistula Lagoon. That's probably a conservative calculation. In any case, my doubts are instantly swept overboard. Soon "Raukar" is rushing towards Frombork.

"At best, you'll be able to turn back!"

The distances on the Polish part of the waterway are manageable. After two hours, Tolkmicko lies picturesquely to starboard. I was able to reserve a berth by phone without any problems. I soon meet Miroslav. He is something like the good soul here, handling passenger boats, looking after pleasure craft skippers and motorhome owners. He is always there, and when he has nothing to do, he sits outside and chats happily with his people over a coffee.

He used to work in Düsseldorf, but then Miroslav moved back to his beloved little town with the fish factory on the harbour. Later, I follow the scent of smoked fish on the eastern side of the harbour. I find a small fish shop there - everything is delicious!

As the crow flies across the lagoon, it is only 20 nautical miles to Kaliningrad. But the only way to get there is round the outside, across the Baltic Sea. So back through the lock, then out of the twelve nautical mile zone in a weak north-easterly. Poland remains astern. Not a ship can be seen or heard for miles around.

"There's a bunch of military on the road. The Russians might not even let you in, at best you'll only be able to turn round. Or they'll capture your ship!" The concerns of friends and acquaintances who knew about my plan were manifold. And yes, of course something like that could happen. But to put it another way: why would something like that happen? Because of the war in Ukraine?

Entry to Kaliningrad past Pillau and military ships

I push my thoughts aside and head east at midnight. In the morning I reach the approach buoy Baltyisk 1. From here, a fairway on the Russian side leads past the old Pillau fortress and on to the lagoon.

The wind falls asleep, the sea lies flat in front of me, the silence is only broken by the hammering of my engine. The haze over the water dissipates as the sun rises. Gradually, a few warships peel out of the haze. The AIS remains silent. There is no radio call. The ships are underway. Every now and then a small diesel cloud appears, standing alone above the leaden sea. One of the ships is moored near the first buoy. "The watchdog," I hear myself whisper.

The people here are open and approachable. They don't emphasise what divides us. For them, what connects us is more important - not least as sailors"

It almost looks like an exercise is going on here. My hands get wet, I check the handheld radio and clip it to my waistcoat. "Now say something - you can't be completely indifferent if I'm just driving around like this!"

Finally I can't stand the tension any longer and press the button on my radio: "Baltyisk Traffic, this is Sailing Vessel 'Raukar' on the way from Tolkmicko, Poland, to Kaliningrad. Can you read me? Over." As soon as I let go of the button, I get the reply: "Sailing Vessel, please come closer, we have bad connection."

"There you go," I say half aloud, as if someone could hear me. When I look round, there's only a respectable little diesel cloud where the watchdog had just been. The ship itself is suddenly travelling two cable lengths behind me. An escort? No! I overhear a conversation in Russian on the radio in which a captain is annoyed about a sailing boat travelling in the middle of the fairway. He means me! How embarrassing. I swerve over to the edge of the fairway, the other one passes.

We are not prepared for sailing tourists

I am then directed to Pier 81. "Can I take your photo?" I call over to the open pilot boat with two young men from the coastguard. "Njet, njelsja!" No, that's forbidden, shouts the Russian. The man on the outboard motor looks Asian and promptly takes photos of me on his mobile phone. "We must have misunderstood each other somehow," I admit to myself with a grin.

Pier 81 is a landing stage for a ferry, a ramp. Container ships are moored all around, tugboats are parked, cranes are travelling. Trosses descend as steeply as sunbeams onto huge bollards. I walk a little awkwardly alongside the gigantic industrial fenders.

The first words are addressed to me in English. I automatically reply in Russian. However, my Russian isn't that great, even though my wife is Russian. Almost every year we go on family holidays to the former Königsberg and visit relatives and friends there. "Why did you come by boat, you were only there recently by car!" The official points to the stamps in my passport. I stand there with my mouth open, looking for an explanation. "Because I love sailing. And because I want to try out how travelling by sea works."

"Raukar" is handled like a commercial vessel

"But you'll be staying with your mother-in-law, won't you?" asks the officer. "Yes, and bring her the kilo of coffee that's down in the boat," I try to lighten the atmosphere with a joke. To make a long story short: They're not prepared for sailing tourists here. A time-consuming procedure. In between, my wife has to step in on the phone when I'm at the end of my Russian. Then the boat is searched thoroughly. It feels like hours pass before I get the redemptive stamp in my passport. "I've done it - I'm in! Damn, I can't believe it!" I cheer inwardly.

I am told that no German boat has been to the Kaliningrad Yacht Club for three years. I feel like an ambassador from a bygone era"

A long sea canal leads directly to Kaliningrad and is quite busy. Motorboats whizz past, the crews greet me in a friendly manner. Big pots are moored at the modern industrial facilities on the eastern side of the canal. Every now and then, however, a small bay appears, with many pretty little houses on the banks that look like large boathouses to live in.

At last I can leave the canal. The lagoon ahead is as smooth as glass. I find a spot close to the shore and drop anchor. Then I go for a swim. A Russian yacht is anchored nearby. The crew notice "Raukar's" faded black, red and gold flag. They approach curiously.

Getting to the Kaliningrad Yacht Club is complicated

"Do you understand English?" asks the skipper when he realises that my Russian is not so good. His home harbour is only a mile away at the Heidekrug yacht club, where he would love to take me. It would be easy to get there and I could also celebrate my mum's birthday with them. I kindly decline. My destination is the Kaliningrad Yacht Club and my own mother-in-law. Of course, the skipper also knows the yacht club, and he also knows that its approach has changed. "You have to leave farwater on buoy 32, then heading 117 degrees to harbour entrance. And than very carefully on the entrance buoy to the harbour, it's very small!" he explains to me.

Nevertheless, I get stuck no less than four times before I learn from another keelboat how to master the approach to the club jetties: just past the beach.

The club is a hive of activity. Full yachts leave for their evening cruise, others come back in from swimming fun with the children. Lots of optis and cadets are on the water, children and teenagers are scurrying around in the small sports boats. While I'm tying up, a man spots me on the jetty. He looks over and smiles at me. As I disembark, he greets me warmly. "Our daughters live in Germany. You're the first German sailor here in three years." From that moment on, I feel like an ambassador from a bygone era.

He and his wife have their sailmaking workshop on the grounds of the yacht club, he tells me. The two of them take me into town. As the large off-road vehicle bounces through the potholes and sometimes over kerbs, they talk cheerfully and answer my many questions.

The Russian language has a large number of swear words

"We were often in Poland and worked with Polish workshops there," says the sailmaker. Now there are only orders from the Kaliningrad region. But that doesn't seem to affect his good mood. Every pothole he can't avoid gives rise to joyful curses. The Russian language has a multitude of swear words. I have memorised some of them.

It is already the middle of the night when I finally cheerfully climb the three steps to my mother-in-law Olga's front door. I now have four days to see the city, let Olga cook for me and meet lots of relatives and friends. They are all enthusiastic about my trip. "You're crazy, but you're a hero!" I'm told several times.

As a child, Olga used to go fishing on the lagoon with her grandad. That was a long time ago; a lot has changed. But her love of the sea has remained"

The highlight is a trip out onto the Vistula Lagoon with Olga on "Raukar". I promised her that years ago. Now the time has finally come. Olga used to go fishing on the lagoon with her grandad as a child. Now we're having a lovely afternoon at anchor. She's sitting under a parasol in her Sunday best and is simply happy!

The next day we go fishing with me, Uncle Yevgeny and Aunt Tatyana. In the evening, I meet Valentin at the yacht club. His father designs and builds ocean racing catamarans. I can admire one of them on the jetty and have a look round. Valentin's family can look back on a remarkable racing career, they even won a prize in the Fastnet Race once. Now the catamaran is to be shipped to Moscow via St. Petersburg. I could come along and sail down the Volga!

People are looking for common ground

Again and again, I notice a pleasant characteristic of the people here: they look for the similarities between themselves and others, not the differences, the things that separate them! Perhaps one of the most important realisations of my trip. This also includes the fact that those who can speak English also want to speak it.

Take Dmitry Zaritsky, the head of the sailing school, for example. Usually out with the kids in the trainer boat, he radiates an almost inimitable calm and level-headedness on land. He talks about various sailing projects that take place under the auspices of the Kaliningrad World Ocean Museum.

I find the idea of a squadron trip to St. Petersburg and back, for example, fascinating. Four yachts have set off on the 600 nautical mile journey. Since the start of the war, the boats have had to cover the distance non-stop, as they are not allowed to stop off in the Baltic countries or Finland. Also exciting: a flotilla of boats across the Pregel and the canals to the Curonian Lagoon. I'd love to be part of that.

At the end of August, I experience the Night of Open Bridges in Kaliningrad. Sailing ships and pleasure craft sail through the city accompanied by fireworks and music on the Pregel. Then it's time to start the return journey. Sitting in the cockpit on the last evening, I enjoy the warm evening sun and the wonderful atmosphere in the yacht club. What a great experience. I hope to come back again soon. Gladly again under sail.

Text: Martin Schubert