The Ocean Race has not only caused a stir in sporting terms in recent months, but also scientifically - on the subject of plastic waste. During the race, the teams had an automated scientific laboratory unit on board that regularly took water samples from the oceans through which the Imocas were sailing, or rather flying. The first results of the analyses of the data have now been presented by Victoria Fulfer from the University of Rhode Islands:

"It's really worrying that we've found microplastics in all samples so far, from coastal waters to those from the remotest corners of the Southern Ocean. More than half of the samples we have analysed so far contain 500 or more particles per cubic metre of water that are larger than 0.1 millimetres. If we look for smaller particles, we find many more."

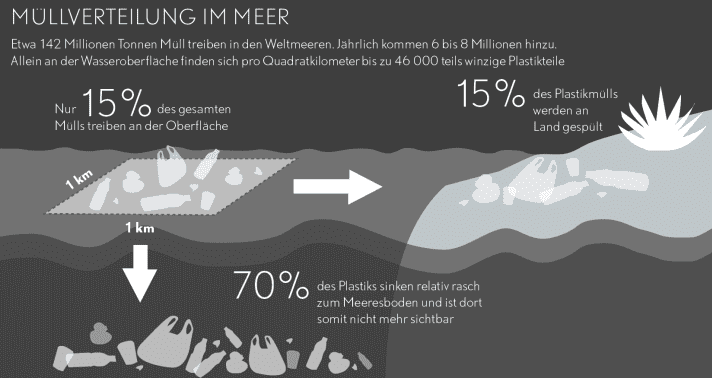

This seems particularly drastic in view of the fact that only 15 per cent of the waste floats in the water (see graphic). By contrast, 70 per cent sinks to the bottom, compacting the seabed and leading to a lack of oxygen. A further 15 per cent of rubbish is washed up on the beaches. The German Federal Environment Agency estimates that around 142 million tonnes of waste are floating in the world's oceans. Depending on the forecast, six to eight million tonnes are added every year.

What sailors can do:

- Use bags or carry nets instead of plastic bags

- Prefer unpackaged products to those packaged in plastic

- Dispose of outer packaging in the prescribed collection containers in the shop

- Do not buy fleece microfibre clothing

- Do not use hygiene products with microplastics (current list: www.bund.net/mikroplastik)

- Do not use disposable plastic cutlery, plates or coffee cups. And no straws either

- Put plastic waste in the yellow bag. Also separate waste abroad if it is disposed of separately there

- Pick up and dispose of plastic waste on the beach and in the water. Take part in beach clean-ups

- Use returnable glass drinks bottles

- Sort plastic waste at home: Remove aluminium foil from yoghurt pots, unscrew lids from tetrapacks, remove leftovers from containers if possible

Plastic waste and the consequences

Plastic degrades extremely slowly

Scientists estimate that it takes around 500 years for plastic to decompose. However, nobody can really say for sure, as most materials have been around for less than 100 years.

The consequences of the waste problem are now well known, probably also because new studies are published almost every month with alarming figures: Seabirds and marine mammals die in agony because they mistake the plastic for food and are poisoned by it or their stomachs are so full of it that they starve to death. Seals, turtles and dolphins strangle themselves in plastic film or abandoned fishing nets. In 2016, 30 whales stranded off Norway, some of them with kilos of plastic in their stomachs. Seabirds die on Heligoland because they become entangled in the remains of nets they collect to build their nests.

Microplastics are even more dangerous. Scientists use this term to describe plastic pieces less than five millimetres in size. Plastic disintegrates in the sea as a result of UV radiation and mechanical stress into ever smaller pieces, which at some point, often only the size of a grain of sand, have a disastrous property: They attract substances such as heavy metals, PCBs and dioxins. In short, they mutate into veritable poison cocktails. This has been confirmed by studies carried out by both nature conservation organisations and German environmental authorities.

In 2017, it also became known that plastic from the sea has long since reached humans via the food chain. This had previously only been vaguely feared. Investigations carried out by NDR this year show that microplastics can be detected in fleur de sel, an expensive French sea salt. The particles are so small that they cannot be separated from the salt during production and are not visible to the naked eye.

Signs of hope

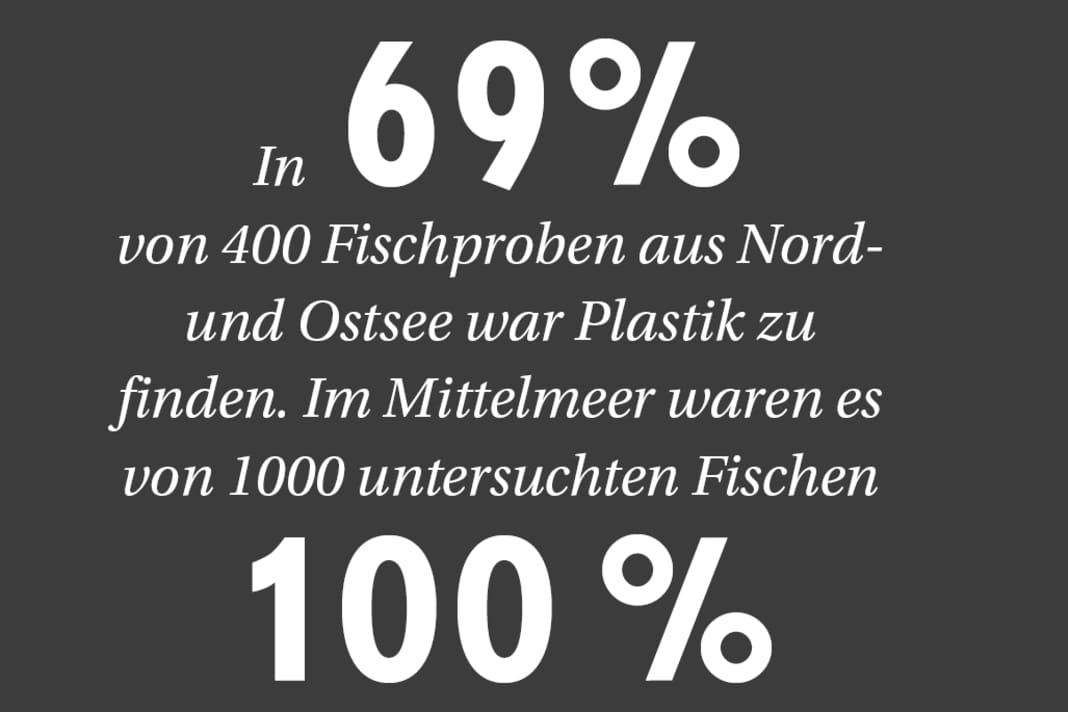

A study by the Federal Environment Agency shows that 69 per cent of 400 fish samples from the North Sea and Baltic Sea were contaminated with traces of plastic. A comparable study by the Greek non-governmental organisation (NGO) Archipelagos on 1,000 samples taken from 167 Greek beaches found that 100 per cent of the fish there contained traces of plastic. Traces of plastic were also found in shellfish that had been sold commercially.

The director of the award-winning documentary "Plastic Planet" (www.plastic-planet.de), which is well worth seeing, dared to conduct the ultimate test of what this means: Austrian Werner Boote had his blood and that of his team analysed by a laboratory. All of them had traces of plastic components such as bisphenol A, phthalates and flame retardants in their blood plasma.

Littered beaches

Equally alarming are the results of sediment samples taken from beaches by various institutes for European or global studies. Even in remote locations, such as on one of the Pitcairn Islands in the South Pacific, researchers counted 670 pieces of waste on one square metre of beach. If they dug ten centimetres deep into the sand, they found an incredible 4,500 pieces. Sailors know beaches like this. Anyone who has anchored in a bay on a Greek island that is open in the direction of the Meltemi will sometimes come across knee-high plastic waste on the shore.

Things don't look much better here in Germany. Recently, 831 pieces of microplastic were collected on one square metre of beach on Lake Starnberg. How it got there is relatively obvious to researchers: The tiny pieces can even be found in treated wastewater, so they often come from scrubs, shower gels or detergents. And nothing holds them back, warn the German Federation for the Environment and Nature Conservation (BUND) and Greenpeace. The Federal Environment Agency is therefore currently systematically analysing wastewater, rainwater and even drinking water for residues.

The situation is therefore worrying. Especially as plastic consumption is increasing unchecked both worldwide and in Germany. The much more important question is therefore how we can prevent a plastic disaster in the coming decades.

Cleaning the sea of plastic waste

Initiatives to clean up the oceans have recently attracted a lot of attention, such as that of the young Dutchman Boyan Slat with his "Ocean Cleanup" project. As a 17-year-old in 2011, he came across more pieces of plastic than fish while sailing and snorkelling in Greece. With youthful fervour, he developed a plan to "clean up" the oceans.

Slat is now a student in Delft. With the support of universities and industry, he has developed a system consisting of "collectors" that resemble classic nets and are around two kilometres long. Two tugs pull it through the water at just 1.5 knots and collect the plastic. Fish and creatures can escape through sophisticated escape openings. Transport ships take the flotsam on board and bring it back to land. The project has now fished 2.7 million kilograms of plastic out of the Pacific. An even larger system is in the works and the project continues to develop. As most of the plastic ends up in the sea via rivers, work is now underway on boats that will tackle the littered river courses, particularly in Asia, to prevent the plastic from reaching the sea in the first place (www.theoceancleanup.com).

Günther Bonin's "One Earth, one Ocean" initiative has also been gathering experience on a smaller scale for two years. The Munich native and his fellow campaigners designed the "Seekuh", a twelve-metre-long waste collection catamaran (www.oneearth-oneocean.com). "Our concept is not to wait for the rubbish to come to us. We go to the places where it ends up in the sea. And these are mainly the large estuaries," says Bonin.

On site, the boat pulls through the water at a speed of two knots and sifts out plastic with the help of nets. Once two tonnes have been collected, the net is closed and fitted with buoyancy bodies and a transmitter. It can then be picked up later by a collection vessel.

"We are also planning a processing ship," explains Bonin, "which will separate the plastics directly on board, recycle them or process them into crude oil." The extracted raw materials could then be returned to the economic cycle in the harbour. In this way, the whole thing should not only be financially viable, but also generate a profit.

The aim is to deploy the collection boats en masse and autonomously. "The first one is currently being used off Hong Kong. The local population is very interested," says Bonin.

Sailing celebrities in the fight against plastic waste

A famous name in sailing has also dedicated herself to the fight against plastic waste: British ocean icon Ellen MacArthur has been fighting for marine conservation with her foundation for years. With her "New Plastics Economy", she wants to eliminate the causes of the problem and help implement a closed-loop economy more quickly. The collection projects make sense. However, many researchers agree that they can only remove a single-digit percentage of waste from the sea, as it sinks to the bottom too quickly.

MacArthur not only relies on political lobbying to persuade governments to impose stricter requirements, she also approaches companies and local authorities directly. It has already been able to commit eleven global corporations to ambitious recycling targets. In addition, the foundation awards an annual prize worth one million dollars to companies that develop important technology for the circular economy - and it supports the companies for a further year in order to develop the products to market maturity as widely as possible.

A project by the German Fraunhofer Institute also benefited from this in 2017. Researcher Dr Sabine Amberg-Schwab developed a compostable, very robust transparent film made from biopolymer, i.e. renewable natural raw materials.

Slow change of direction

Such initiatives are proving to be important building blocks for a paradigm shift. Politicians, with their time-consuming legislative and administrative processes, are often too slow to drive rapid change.

Take the example of microplastics in cosmetics: publications by many nature conservation organisations and the media about the dangers of tiny abrasive or clouding particles for milky and viscous cosmetics alarmed many manufacturers. They were also found in abundance in toothpaste, which people can easily swallow.

As a result of public pressure, only one toothpaste (according to BUND, the product Parodont from Beovita) containing microplastics is still on the market today. Many cosmetics manufacturers, such as Beiersdorf, have also declared that they will gradually replace plastic with harmless ingredients in other products over the next few years. However, nature conservation organisations criticise such voluntary commitments because exceptions are often made or other problematic substances are used.

Countries such as England and Sweden are quicker in this respect. They adopted bans on microplastics in cosmetics in 2017. The German government has not even called for this yet, although the Federal Environment Agency strongly recommends it.

China as a pioneer against plastic waste

However, the discussion is really gaining momentum thanks to the current biggest source of plastic waste in the oceans: China. The government in Beijing caused a veritable earthquake in December when it announced that it would practically stop importing plastic waste from Europe from January. It said it was tired of being the world's rubbish dump and would set up its own circular economy for plastics.

It was long overdue for Asian countries to start tackling the problem of plastic waste. "We have analysed studies on waste discharges from rivers into the sea," reports Dr Christian Schmidt from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig. "This showed that the highest plastic load worldwide comes from ten rivers, all of which are located in Asia or Africa."

The Yangtze, for example, transports around 100,000 plastic particles per 1,000 cubic metres of water. By comparison, the Rhine carries around 1,000 particles - which is still an alarming amount.

"But it makes no sense to point the finger at the Asians now," says Schmidt. After all, the beaches on the North and Baltic Seas are also full of plastic, and that definitely comes from Europe. And it is also clearly noticeable that there is now movement on the issue in Asia. Schmidt: "In countries like India, there is practically no functioning waste management in many areas. Rivers are the waste disposal system there. They now want to change that."

China's surprising change of course has caught the Europeans, who like to present themselves as extremely progressive when it comes to recycling, off guard. Right up to the end, they tried to negotiate a transitional period of several years so that they would not be left with a mountain of waste in the future. The concern is justified. More than half of all plastic waste produced in the EU was exported to the Far East. Almost ten per cent of the six million tonnes of plastic waste produced in Germany each year also went to China.

Europe is catching up in terms of plastic waste

Hectic activity is now breaking out in Europe. "We need to invest more in better recycling and sorting facilities," said a spokesperson for German waste recycling company and industry leader Remondis recently in the German newspaper "Die Zeit". It is not only necessary to decide on high recycling quotas, but also to oblige the industry to use certain proportions of recycled materials in the production of plastic. Up to now, many recycling companies have been stuck with their recovered raw materials as they are relatively expensive compared to new production due to low oil prices.

It is therefore fitting that the German government and the EU have just published their new targets with regard to planned packaging legislation. The EU Commission has stipulated that all plastic packaging should be recyclable by 2030. A recycling rate of 55 per cent is to be achieved by 2030. An EU initiative on microplastics in cosmetics was successful: With the help of voluntary commitments, almost all manufacturers have already switched to plastic-free products.

In order to boost implementation in all areas, the EU is supporting corresponding research projects with 250 million euros until 2020, after which a further 100 million is planned. But that doesn't necessarily mean much. Some countries, including Germany, often do not adhere to the EU's agreed environmental targets. Take plastic bags, for example. Every Mediterranean sailor has probably encountered them floating in the water - or worse still, they have ended up in the propeller or intake nozzle of the cooling water circuit.

The end of plastic bags

Back in 2016, the EU made it mandatory for member states to take appropriate measures to reduce the use of plastic bags by half by 2017 and by as much as 80 per cent by 2019. Ireland, Finland and Denmark had already proven that a tax on plastic bags is extremely effective. Consumption in Ireland fell from 328 bags per citizen to just 18 after the introduction of a two-stage tax of 22 cents and then 44 cents per bag a year later. Finland and Denmark even managed to reduce consumption to four bags per capita.

In 2010, every German still used an average of 64 bags. Nevertheless, the German government did not want to impose a similar tax. However, large plastic bags have now been banned at checkouts across the EU since 2022. However, the use of very thin plastic bags in the fruit and vegetable section or at the checkout is still not banned. In 2020, every German still used an average of 46 of these plastic bags per year.

Another EU success was the ban on plastic drinking straws, disposable cutlery and plastic plates, which came into force in 2021. It is now in force and the catering and retail sectors have implemented it relatively quickly and quietly. An example that gives hope.

Avoid plastic if possible

In any case, the clean image of the Germans has been tarnished since it became known that over 50 per cent of German plastic waste, which is painstakingly collected via the dual system, ends up in waste incineration - or, as mentioned above, is exported to China and now to African countries as a substitute.

At this point at the latest, it becomes clear how complex the issue is and how powerful the interests of some industry lobbies are. Rapid intervention by the state is prevented time and time again.

However, water sports enthusiasts who want to contribute to cleaner oceans and unpolluted food still have a few options. It is as simple as it is effective to change your own consumer behaviour accordingly (see tips above) - in other words, avoid plastic wherever possible. Support waste separation. Sensitise the next generation to the topic.

Public pressure can make a big difference, as the example of toothpaste and cosmetics in general shows. And this is the only way to ensure that the sailing areas that are already attracting millions of crews today will be preserved for decades to come.