North Sea round: Philipp Hympendahl in the footsteps of Wilfried Erdmann

Philipp Hympendahl

· 27.08.2022

Read also:

It's been a little while since I last cruised along the Norwegian coast on a sailing boat. I was 17 years old at the time and travelling with my father. A certain Boris Becker won Wimbledon the day before we arrived in Bergen. Now the fallen tennis idol is in prison and I'm heading north again.

In the early morning of 21 May, I stand down by the companionway and watch as the rising sun drives away the night. Gannets and great black-backed gulls glide close over the crests of the waves, almost caressing the waves with their wingtips without ever touching them. They accompany the "African Queen" all the way to the rocky coast of southern Norway. The Ryvingen lighthouse on the offshore island of Låven slowly approaches. I leave the flat, rounded rock to starboard and enter the shallow bay of Mandal. The harbour entrance must be to the left of the beach, but there are only shimmering beige rocks; there's no sign of the town either. Then I spot a small boat travelling parallel to the beach towards the rocks. It must go in there.

Nothing is more sublime than encountering solitude and vastness alone in a small boat.

I arrive in the modern harbour in sunshine and cool winds and moor right next to the friendly German single-handed sailor Hermanus. He has converted his quarter-ton "Jenny Greenteeth" himself and is well equipped. Among other things, he has a kayak on board, cut into three parts, which he puts together with quick-release fasteners. A tinkerer who keeps everything in top condition. After a welcome beer, he recommends: "You absolutely have to go to the viewpoint in the village, from there you have a great view of the sea." Grateful for the tip, I later enjoy the view of the white houses of Mandal, the harbour and the horizon beyond.

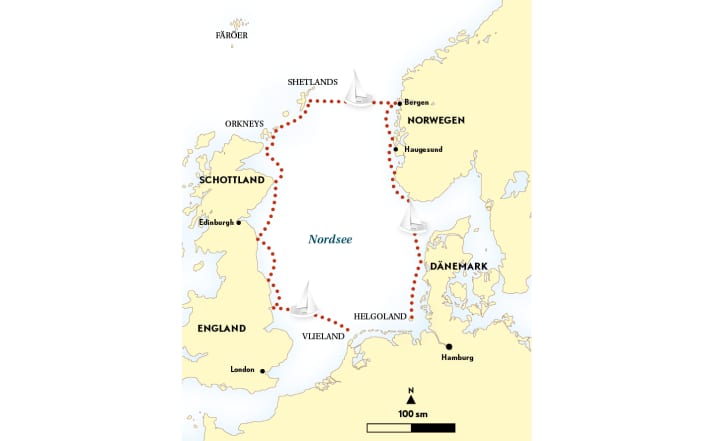

Inspired by Wilfried Erdmann's book "North Sea Views", I have decided to sail a similar route, a little shorter, but full of the varied challenges of the North: light and darkness, ebb and flow, experiencing the gentleness and roughness of nature up close. With my boat, I want to become a playmate of the elements and survive. Nothing is more sublime than encountering solitude and vastness alone in a small boat. Nothing makes me feel more alive, nothing makes me happier and more humble.

I've just completed the first long beat from Heligoland, two days at sea with calm, wind and waves. I want to use the next day to get further west before the wind shifts. I sail along the hilly coast past wind turbines and small towns and finally, after 64 nautical miles, into the fjord at Egersund.

Egersund is a prosperous, traditional fishing village that can be visited in all weathers. The small marina is run by club members. I buy a fresh salad from the supermarket and a cold beer from the bilge. Wolfgang, a fatherly friend and area expert, advises me on the phone: "Why don't you go to Skudeneshavn next; you can forget about Tananger, it's not so nice."

I follow his recommendation and two days later I motor under the 22 metre high Eigerøy bridge in the morning, following the fjord towards the north-western estuary. I pick up my camera several times and take pictures of dream houses that seem to merge with the rocky landscape.

I reach the coast in a light breeze. But soon the wind picks up. As it continues to rise and the "Queen" starts to surf, I have to recover the main - a sporty exercise. Turning the boat into the wind under autopilot in the waves and pulling down the wildly flapping sail on the mast takes strength and nerves. I'm glad when it's done and I can sail downwind in a controlled manner.

In the bay in front of the harbour entrance, where it becomes shallower, the waves build up once again to say goodbye and send my 9.20-metre half-tonner from the 1980s into the Skudeneshavn canal with a threatening farewell salute. A nice Dutch couple on their Sun Fast 42 help me find the marina and arrive shortly after me. We are the only sailors, and there is no classic marina, we are moored on jetties right in the town. Together with Alette and Martijn, I sail 18 challenging nautical miles through narrow fjords with very gusty winds to Haugesund the next day.

We are moored directly in front of the Maritim Hotel, opposite the boat of the well-known Norwegian extreme sailor Erik Aanderaa, who I visit spontaneously the next day. We talk for a while about his trips and how difficult it can be to realise ambitious plans.

The next day it's blowing at 40 knots. Instead of sailing on my own keel, I take the ferry to Utsira with Bert, a German, and Martijn. The island is famous for its birdlife, but for a few years now it has also been known - unusually enough - for its street art. The smallest municipality in Norway with 200 inhabitants is adorned with graffiti of the highest quality. All over the island, on houses, silos, windmills and rocks, artists from all over the world have been able to express themselves.

Then we go our separate ways. Martijn and Alette want to explore the Hardangerfjord, Bert and his wife set off with me in a calm. We get lost off the coast as I search unsuccessfully for the wind further out to sea, while the two of them motor northwards along the coast.

Suddenly I see a long, pointed dorsal fin: an orca.

I don't find much wind that day, but suddenly I see a long, pointed dorsal fin: an orca. By the time I'm back on deck with the camera, it's a small herd swimming around me before suddenly disappearing. This is not to be the only encounter.

I have chosen a quiet anchorage as my destination for the day, but on the way there under motor I pass two islands that are only connected by a flat stone wall. Curious, I motor in to take a closer look. They are marked on the map as northern and southern Lyklingholmen. Between them is a lagoon like in the South Seas. A chance find, beautiful and almost untouched.

I tie up at a mooring and paddle ashore with my SUP to a wooden jetty, behind which is a shed and a slipway. Further up on the rocky hills, scattered among bushes, mosses and lichens, are three wooden houses. On my way up a narrow path, I meet one of the owners; Ewen, a nice, quiet man, tells me that his father-in-law grew up here and was brought to the mainland by boat as a child to attend school. What a remote place to grow up. Today, nobody lives on the islands permanently.

My next destination is Selbjørn, a harsh contrast with its ugly industrial harbour. But a local recommends Bekkjarvik nearby, which actually turns out to be a cosy place with wooden houses, a small marina and one of the best restaurants in Norway. As I have neither the wardrobe nor the budget for the temple of gastronomy, I cook a cosy meal on board. Before that, I use the modern sanitary facilities for a long shower.

In the morning, I pay a visit to a nice German couple on a large aluminium yacht. It's one of those encounters that I often have as a single-handed sailor. In general, I noticed the special friendliness of the yachties on the trip in the north. Many Dutch, German and Norwegian couples often go on longer trips on relatively small boats and are very open and welcoming. A closeness that I really appreciate as a person and that takes the loneliness out of a solo trip.

An important stopover on my journey is Bergen, for the sake of old memories and because it marks the northernmost point of my journey. In the early evening of 1 June, the cruise ship "Mein Schiff 4" comes to meet me and I greet the waving guests on their balconies before mooring in the city harbour shortly afterwards. The weather lives up to the town's reputation as a precipitation hotspot: it's raining and hazy. The Fløyen mountain plateau is shrouded in high fog.

After two days, I leave the wettest city in Europe with the last drops of rain. It's supposed to stay fine for a week from tomorrow. But I still have a lot of sailing ahead of me. My plan is to sail to Kleppesjøen: a favourable starting point for my long trip to the Shetland Islands.

While I wait there for a weather window, tension spreads; waiting is difficult for me. I use the time to prepare myself and the "Queen" for the passage. I take screenshots of the weather app forecasts, stow my folding bike and SUP, put drinks and snacks in the cockpit and then I'm ready. We finally set off on 5 June in sunshine and pleasant temperatures. There is still little wind in the land cover, but later it will pick up and turn to the north.

Initially focussed and controlled, I gradually get more and more into the rhythm of nature.

Long stages always follow the same pattern for me. Initially focussed and controlled, I gradually get more and more into the rhythm of nature. Fears and misgivings are left behind once I reach land. The loneliness and the endless expanse of the sea then don't seem like a threat, but like constant, familiar companions. At best, I manage to become a part of it. Being able to give free rein to my own emotions is the luxury of single-handed sailing, that's what I love about it.

A gannet accompanies me, swoops into the water with its wings folded, drifts back a little and then takes off again. Smiling, it flies alongside the boat, looks into the camera and stays with me for a while. I offer him bread and conversation, but he just wants to fly.

On a half-wind course at five Beaufort, the bow cuts powerfully through the waves, heading due west towards the setting sun. Averaging almost six knots, I rush through the daylight night and reach the coast of Shetland after 33 hours and 200 nautical miles. A loud "Land in sight!" escapes me, an expression of satisfaction as well as relief.

Geological evolution seems to have followed completely different laws here than in Norway. While the rocks there appear to have been sandpapered round, the coast here is like a knife cut from a piece of Gouda cheese; above it lie even hills in lush green.

A few metres from my boat, a black, pointed dorsal fin emerges from the water.

The next beat should take me to Fair Isle, an almost mystical place that is on the bucket list of many North Sea sailors. This is where the North Sea meets the Atlantic; the sea area is notorious for its big waves. In good weather, I only experience a long swell, but it gives me an idea of what it could be like here. When I hoist my mainsail a few nautical miles from the island, I experience the most exciting natural phenomenon of my sailing life so far. A few metres from my boat, a black, pointed dorsal fin comes out of the water. I immediately recognise from its powerful slowness and the white spot that it is an orca, a killer whale.

I immediately grab the camera and point it aft. A second orca appears directly behind my wind vane, shimmering black and white just below the surface, then it turns away. My joyful excitement is now mixed with respect and fear. Stories of orca attacks off the Portuguese coast are running through my mind. At that moment, the other whale chases after me and comes very close to the rudder blade. But then it surfaces, turns away and they both swim off.

It happens so quickly that I can hardly believe it myself. I don't get to rest for a long time. Only an evening walk on Fair Isle brings me back to normal. Unfortunately, the timing is not ideal for exploring the island. There is an unpleasant swell in the harbour. The following day is the last chance to get to the Orkneys before the next low. I make the most of it.

To reach Auskerry Sound, which will take me to Kirkwall, I struggle with the height in force six winds on an upwind course. I only make it to the headland of Lamp Head after a tack and a long beat to the east, but I am again very lucky with the wind direction, which favours me over the forecast. After a good twelve hours and 62 miles, I reach the sheltered harbour of Kirkwall in the early evening.

Another trough of low pressure passes through, and the next one is already on the horizon.

I would have to wait a long time to explore the beauty of the small islands and anchor bays, so I leave the Orkneys without having seen much. With a stern wind, I head towards the Scottish mainland, only getting uncomfortable once at the eastern end of the notorious Pentland Firth, where the waves run riot.

The east coast of Scotland and England offers few harbours that can be called at at any time. You either make long hauls or you have to plan very carefully. I opt for the long haul from Wick in the north-east of Scotland to Peterhead, a larger town with a fishing and industrial harbour and a sheltered marina at the end of the large bay. Sailors from the south who want to continue on to the New Caledonia Channel usually moor here.

A gust of wind pushes me onto my side - a first hint from Rasmus

As I leave Peterhead and unfurl my headsail outside the long quay walls, a gust pushes me fully onto my side - the first sign from Rasmus, followed by others. One moment the wind is so light that I seriously consider setting the main, and five minutes later I'm battling the elemental forces with a headsail rolled away into a towel. Because the wind is blowing offshore, the gusts are particularly treacherous.

In the end, it's the wind that persuades me to go into Aberdeen. The city has no marina, so I ask on canal 12 for a place in the commercial harbour, which doesn't promise much comfort: three metres of tide on a rusty pier for 30 euros a night, with no toilet, shower or internet - you rarely get that.

The next day is also exhausting, a wind farm under construction gets in the way of the "African Queen" and I am asked by radio to sail well clear of the area. A difficult endeavour with increasing wind and swell. The aft wind continues to pick up as the night progresses. As I stand at the companionway as darkness falls and watch the wave crests lift the stern from behind and accelerate the boat, I realise how serene I have become and how much confidence I have gained in myself and the boat. In conditions that would have made me nervous in the past, I can now lie down and sleep.

Whitby, where James Cook once matured into a sailor, is the last harbour in English waters. The resort town with its historic wooden houses and the ruins of an old abbey looks inviting. I start an extensive fish and chip test, which confirms the harbour master's tip: "Papa's" makes the best.

From here, I plan to sail in one long stroke to Vlieland, the queen's stage of my North Sea tour. The nautical chart shows all the obstacles the sport has to offer - in addition to wind farms, oil rigs and a training area for submarines, there are three traffic separation schemes on the last few miles, when tiredness slowly takes over.

The Whitby swing bridge releases me and numerous other sailors from the marina, past the promenade, through the pier head out to sea. Most of them head north, one south, only I sail away from the coast. At first I set sail in a light breeze. Only when the wind shifts during the night and picks up later does my half-tonner really get going. On the first evening, I have to sail round a huge wind farm that, according to the paper chart, should actually still be under construction. A warship announces its position on channel 16 with the order to keep clear. The endless expanse of the sea shrinks to the size of a beer mat in some parts of the North Sea.

As predicted, the wind turns in my favour, picks up a little and accelerates the "Queen" and me to eight knots in places. Suddenly a particularly large wave crashes against the hull, flies horizontally over the boat, past the sprayhood. I watch mesmerised through the companionway, watching the flying water and feeling a bit like Boris Herrmann. Now please don't suffer a similar fate just before the finish line; after weeks without incident, I can well do without a collision with a fishing trawler.

As I begin to tire, the opportunity to sleep has already passed. We are approaching the traffic separation schemes, the section of my journey that I have the most respect for. And so I am suddenly wide awake again. A few freighters pass to starboard, I have to reduce speed, furl the headsail and furl the main.

I carefully pass behind the next freighter. I pass the "motorways of the sea" with the sun rising and lots of shipping traffic. Then it's done. Ahead, the small island of Vlieland is slowly getting bigger.

Relief settles over the tiredness. And this indescribable feeling of happiness.

Read also: