Forgotten history: How a Bavarian builds a sailing boat and sails to India

Marc Bielefeld

· 19.08.2023

The man speaks of his vehicle in the "we" form, "my vehicle and I" he writes in the slim foreword to his monstrous book. He is referring to a sailing boat and this guy who built this very boat with his own hands, without any knowledge of boat building, without any support, virtually without any money. He was tall and still young when he realised the unthinkable. A Bavarian with a "mighty, powerful handshake", as an editor of the "Münchner Zeitung" recalled during the turmoil of the Weimar Republic.

One day, this dervish burst into the editorial office and held a report in his hands that he had written himself and that alone was quite something. He wanted to see Albania and the revolution for himself and had travelled through the dangerous country on his own two feet. He met poor farmers and quarrelsome rebels in the mountains, sat by the fire with tribal leaders and made his way through a country in a state of emergency. The editor read this young man's account of his experiences and asked him: "You really experienced all this yourself?" He bought his words and printed the entire text.

The two stayed in touch. Months later, they met again, the editor and this man from the middle of nowhere in Munich who was difficult to categorise. These were not easy times. The First World War was over, the chaos before the next one was already underway. It was 1927 when the burly Bavarian turned up again, this time with a nasty foot injury that he had allegedly sustained in the Swiss Alps. He dragged his leg behind him, limping badly, but he dismissed his walking disability as if it were a scratch. After his adventure in Albania and the odd climbing trip, the man had long since made other plans. This time, he said, he wanted to reach for the oceans. He wanted to sail, far away and on his own, he trumpeted to the editor. He was quite astonished - but didn't think anything was impossible with this guy.

Setbacks during the construction phase

"Despite his foot, he wasn't the least bit downhearted," the newspaper man later recalled. "On the contrary, he talked about the tricky sailing boat he was currently building to take on a trip around the world." He suffered a number of setbacks during the construction phase. Material problems, construction issues, lack of money. But the lure of the seas swept all obstacles aside. The editor named Jozef Magnus Wehner recalled this: "One day, the boat was as seaworthy as it could be, and Hans Zitt set off - into the free, wild world, with just a few marks in his pocket, his head full of bold plans, until the irrepressible faith in this man set sail."

So the young "daredevil" soon climbed into his little boat, set off from Ingolstadt in his "daring vessel", first travelling across the Danube before finally setting sail on the Black Sea and then the Mediterranean. He left heated Europe in his wake and instead set course for foreign parts of the world, for "sun and storm", steering into a fabulous experience of "wind, salt air and the smell of harsh human wilderness".

A forgotten book

When he returned, and he did return, he also put this journey down on paper. The result is a now forgotten book entitled "Ein Mann, ein Boot, ein fernes Land" (A man, a boat, a distant land), published in 1937 by Leipzig-based Schwarzhäupter-Verlag, with a very brief foreword by the man we are talking about here. The German sailor Hans Zitt wrote there, still narrow-gauge: "I went out once and returned home again. It would take volumes to fully record the wealth of events on this great voyage. So I wrote a brief report. The two of us - my vehicle and I - were completely on our own for four stormy years and wandered restlessly into ever greater distances - all the way to India."

What kind of person was this Hans Zitt? Where did he get his courage, his determination? No one can say. But we do know who his role model was. In the first chapter of his book, Zitt pays tribute to the man who spurred him on to his escapade. In those years, a young officer of the German South America Line also ventured on a voyage that went down in history at the time: Franz Romer announced at the time that he wanted to cross the Atlantic in "rubber shoes" and make it to the West Indies in a folding boat. "An event", as Hans Zitt writes, "that had no equal in the history of seafaring."

And this Romer actually set off. From Lisbon, he headed out into the Atlantic via the Canary Islands, all alone in his six-metre-long boat, thirty centimetres high and covered only with a thin rubber skin - "seven thousand kilometres of green, bare water" in front of him. Romer really did make it to the Caribbean. "Restless in the lonely ocean", as Hans Zitt called it.

He immediately caught fire. He thought about it. He immediately fantasised about going out to sea himself. This was an adventure to his liking, even bigger, even more outrageous than anything he had dared to do before. And Hans Zitt encouraged himself: "If Romer manages to paddle across the Atlantic in a folding boat, then I will also succeed in making my way to India or China in a much larger, solid sailing boat."

The decision was made

His decision was made. He was heading east. Across the sea and with nothing but a 50-mark note in his pocket. It turned into four years and "thirty thousand kilometres of the world", as Hans Zitt writes. It became a journey on which his equipment consisted primarily of "will and confidence". And from the first to the last day, according to Zitt in his book, the journey was characterised by "obstacles of all kinds". He was shipwrecked on the Danube, stranded near Vienna, hit the winter ice, weathered Europe's rough river landscape and worked his way through the Carpathian Mountains with his boat. He then crosses the Gulf of Smyrna, soon has Africa in front of his bow and cruises through the "hell of the Red Sea". Finally, he sails through the "Gate of Tears", survives the law of the desert in Arabia - and finally ventures 1,500 nautical miles across the open sea to India.

The title of the book, which is now long out of print, is adorned with a green drawing of his boat. Brand self-built. An open boat with a long tiller, a gaff-rigged mainsail and a flying jib, with a small cabin and a sliding hatch at the front. Hans Zitt himself called his little boat a nutshell. And that's all it was. Nevertheless, he summarised his journey at the end with words that seem like self-mortification in the comfort zones of today's world. He writes: "The journey from Munich to India was the experience of my youth. It was arduous - that's why it was beautiful."

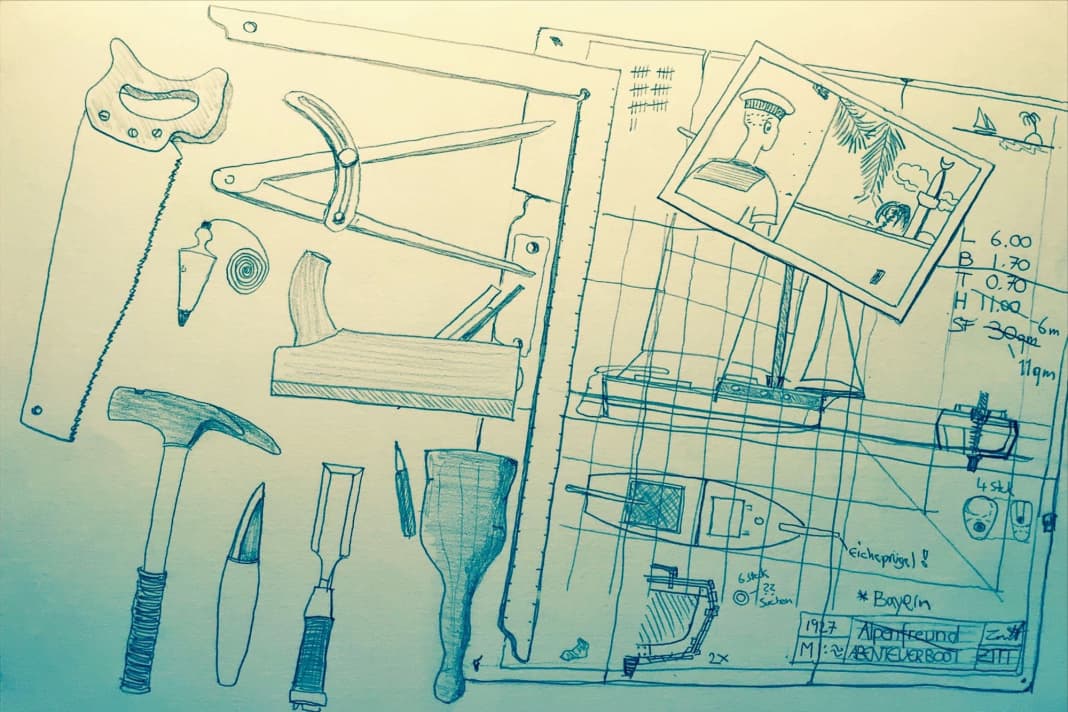

Building a sailing boat according to instructions

For Hans Zitt, the hardships begin with the construction of the boat. No wonder he initially considered setting off on foot with just a rucksack. For a while, he also toyed with the idea of travelling to India on horseback. But even a decent leather saddle would be beyond his budget, as he learnt when he visited a saddle maker in Munich. Finally, he discovers a "thin red booklet" in one of the bookshops of the time, entitled "Spiel und Arbeit - wie baue ich mir ein Segelboot?" (Play and work - how to build a sailing boat). Zitt, in his early 20s, buys the book. He pays a penny for the childish handicraft instructions: the primer is actually written in rhyme.

The next day, he dedicates himself to boat building in Munich and draws up over a dozen construction plans. He goes to a timber merchant and is soon standing in front of a sawing machine and planing bench. He lays the keel and starts planking. He caulked, tarred, painted, carpentered, forged and sanded - all by hand and all alone. It takes him seven "bloody months" to finish his boat.

And this is what his Indian vehicle looked like in the end. The ship was made of fir wood, the frames of "arm-thick beams". It was six metres long, 1.70 metres wide and had a draught of just under one metre. There was a cabin at the front and a folding table, which he soon threw overboard again. And as small and simple as the boat may seem for such a devil's journey, Zitt found it to be so: "The cabin was very comfortably furnished and had no fewer than six portholes. As I couldn't get hold of any frames in Munich, I used cooker rings." He then sewed the sails from canvas: the boat was supposed to have 30 square metres of wind, supported by a "monster of a mast" that measured eleven metres and was fitted with various iron fittings. However, the sails were far too big, as he later realised at sea. He cut them up until in the end only a third of the sail area remained.

Simply "Bavaria"

Finally, he needed a name for his ship. Zitt thought about it. After considering the boat names "Oberland" and "Alpenfreund", he finally wrote six simple letters on the red-painted stern of his boat. It was simply to be called "Bayern".

In the meantime, his journey had been announced in the newspaper and several companies equipped him. Klepperwerke provided him with waterproof overcoats and southern vests, the Knorr pea sausage factory sent its own soup paste, another company contributed a carton of malt coffee and another 25 kilograms of chocolate. On top of that, someone gave him a box full of glass beads so that he would have barter goods in faraway countries. This resulted in a "considerable stockpile of goods", as Zitt writes in his book. Enough for a "cosy Robinson life".

He soon pulled his boat out of the Munich shed, loaded it onto a railway wagon and transported it to Ingolstadt on the Danube. He checked the nails and fittings once again and ran his hand over the fresh hull. Then there is only one thing left for the intrepid man: "It was time to disappear."

As soon as he enters the creek, his boat begins to sink. Water is pouring through the plank joints everywhere, the boat has to get out again. Re-sealing is the order of the day. Zitt smears tar into the joints, plugs them and lets the wood swell in the water.

Not travelling alone on a sailing boat

Then they finally set off down the Danube. And at this point, Zitt has another companion on board, a tailor, who he hopes will not only be able to sew his shirts and trousers, but also the sails. They head south, looking out over unspoilt land and blue mountain ranges. They drift over shallows, navigate past reefs and pass through the Vienna Woods. And: the boat is doing surprisingly well for a self-build.

The Danube becomes wider and more powerful, soon they set sail for the first time and make good progress. At a stop in Vienna, Zitt is to give a lecture on his crazy plan; an enterprising Austrian wants to market the trip. They have posters printed and book a room in an inn. But nobody turns up. The Burgenlanders probably think it's rubbish. All the way to India in such a tiny boat? That can only be a lying baron.

Night-and-fog campaign

Autumn comes, the cold, then: ice. They cross Austria, enter Hungary, steer the boat to Budapest and Belgrade. Almost encircled by ice floes, they turn deeper and deeper into the Balkans. Zitt writes: "The 'Bayern' rocks like a carriage horse on the waves, the lantern rattles in the wind high on the mast." Then they even have to reef in the middle of the river. "At times, the stern dips up to the jib, and with the mainsail reefed, the boat cuts through the current at high speed." Finally, the border with Yugoslavia is approaching. Zitt learns that the customs authorities at the border want a deposit for the boat - until he leaves the country again. With barely a shilling in his pocket, he finally crosses the border in a cloak-and-dagger operation.

Under a sky of snowflakes, he sails down the Danube, deeper and deeper into winter, deeper into the east. Romania lies on the left bank, Bulgaria on the right. The tailor has long since disembarked and Zitt continues to make his way alone. It is the turn of the year from 1928 to 1929, and this winter is extremely cold. Zitt hears the wolves howling when he anchors in Wallachia at night. Until he puts his boat away for the winter and roams the neighbouring villages on foot. Then he comes to the Black Sea as spring approaches. He works on his boat again, making improvements. He saws off the cabin superstructure and shortens the mast again to have even less sail area. The first trip across open water is now imminent.

The art of sailing

On the Sulina arm, he travelled through an "immense swamp area" until he finally reached the town of Sulina in the delta. The pilots and skippers on the Black Sea warn him and judge his boat to be unsuitable for the journey that this crazy German has now set himself. Zitt writes the doubts to the wind: "The boat still has numerous defects, but the art of sailing has become second nature to me on the Danube voyage. My mind is made up, nobody can dissuade me." Zitt is 22 years old when he sets sail for the Black Sea.

The wind has been blowing fiercely for days, and this is the first time we have experienced real, rough sailing. A dress rehearsal for the small boat and its stubborn captain. In his book, Zitt writes of "furious seas", of a "witch's cauldron" in which he has to cross bars and sometimes can no longer see land on the way south. "The waves crash around me, the sea lashes and crashes against the 'Bayern', a black wall arches up, I can't breathe, the water gurgles and bubbles, the stars twinkle above me."

The sails are as stiff as planks in the storm, he clings to the tiller like iron, but Zitt and his ship miraculously hold on. Zitt speaks of a struggle, and when he repeatedly emphasises that "fear and dread" are out of the question as passengers despite all the adversity, his text sometimes reeks of dubious perseverance propaganda and unbearable German heroism.

Being at the mercy of the elements with a sailing boat

This hardly detracts from his adventure as such. And so far, he has only had a taste of what he is about to embark on. "How completely different the journey across the sea was to travelling on the river. No more boundaries. Only now did I realise the concept of sailing in all its peculiarity, this complete adaptation and being at the mercy of the element, wind, water, rain, storm - completely connected with nature."

Zitt reaches Turkey in the summer. He sailed to the Bosporus and headed for Constantinople, now Istanbul. He "stuck" there for a month, inspected the city and then set course for the Dardanelles, where he visited the battlefields of the First World War. He comes to the Sea of Marmara. Here and there, local boat builders give him a hand to keep the ship in good shape. And in the meantime, an unknown heat hits him in the face. This is Asia Minor, a different world.

Next, he heads along the Greek coast, travelling a long distance across the open Mediterranean for the first time: all the way to Rhodes. And in doing so, he orientates himself on a cruising guide that is as vague as it is illustrious. Zitt writes: "On my more distant voyages through the Aegean archipelago, one book played a major role, and that book was - the Bible!"

Zitt studied journeys of the apostles

It was not so much piety that had driven the book into his hands as the advice of an English sailor who ran a sports shop in Constantinople. "Young friend," Mr Baker had said to him, "if you want to know the best places between the Dardanelles and Rhodes, then get yourself the Holy Scriptures for a few piastres." Zitt then studied the journeys of the apostles in order to make his way further south.

So he spends long months travelling through parts of the world that are completely foreign to him. To earn a few dollars, he works as a mechanic in Turkey, helps with a treasure hunt in Greece and earns the money for the upcoming passage of the Suez Canal by performing as a prizefighter in a circus. The sailing Bavarian with the bear paws is a sensation in the Middle East.

How true his detailed descriptions in the book are ultimately remains an open question. Time and again he gets carried away with dramatic descriptions that all too quickly escalate into boastfulness and also publicise his political stance: Like many at the time, Hans Zitt was an avowed National Socialist, which is also reflected in his "heroic" formulations. However, the adventure alone, beyond all political delusions, was probably enough to make his journey a special one - even if it ultimately only dispels one misconception: travelling educates? No. Travelling does not always make you smart. And even the most daring expeditions through foreign cultures are not necessarily able to open the traveller's eyes, but allow many a mind to continue navigating through the darkness. Even on a sailing boat.

A tough test in the Red Sea

In terms of seamanship, the subsequent journey through the Red Sea in particular must have put Zitt to the test. He had to make do without clean water for weeks, ravaged by malaria. He bobbed apathetically on his boat towards the south, then had to cross hard against it again. At the Horn of Africa, he sails along the Arabian coast and is attacked by Bedouins in Oman. With a clay jug, bayonet and carbine, he set off into the desert one day in search of a watering hole when he was suddenly confronted by a Bedouin who came after his equipment. Zitt writes: "Now I had to be the faster one. The piston hissed through the air - it cracked as if I had threshed on a pumpkin." Sentences like something out of a C-movie.

Finally comes his last major stage, which he gives the title in the book: "1,500 miles of bare sea". The journey across the Arabian Sea to India. He sets off from the coast of the yellow sands, and from now on his best companion is his compass. "The ocean surged in long, high waves. Around me was the sea again, a circular horizon." The crossing is said to have taken eleven weeks, once capsizing in a storm, then again: nothing but water. "Time flowed into space - space into time. It had become a matter of course for me to only see the sky and the sea. I sailed with a cast off, and day by day I moved closer to India."

A "cutter from Germany"

Soon he has no more water. For four days, he was drifting across the sea, on the verge of dying of thirst, when he spotted a steamer: the "Queen of Sumatra", travelling from Ceylon to the Persian Gulf. The large ship sees him and sets course for the small sailing boat. Zitt has shot red. He soon shimmies up the rope ladder on board, and the passengers stare at him. "He's coming from Germany in this cutter?" the people are said to have murmured. He is given water and food, but soon sets off again, further east. Zitt writes: "The eleventh week came to an end. My destination could no longer be far away. The last day had to come - and it did."

And then the coast of the subcontinent does indeed appear in front of his bow - a good three years after he left Germany. More precisely: "Three years in a miserable boat that other people wouldn't have trusted to sail across a local lake."

Palm trees stand on the beach, butterflies fly around his nose "like living emeralds". It is the greeting of the tropics. Shallow ships come towards him, accompanying the curious stranger to a nearby bay. People soon gather around him, communicating with hands and feet. Zitt writes a disturbing sentence: "None of the lads reached up to my shoulders. I had no fear of them, because I knew that the dangers of this country, unlike Arabia, were to be found elsewhere than among a population that is peace-loving and devoted and has been used to being ruled for thousands of years."

Arrived in India with the self-built sailing boat

Hans Zitt has arrived, but he doesn't even know where exactly in India he has landed. He only learns where he is from an Irish missionary: just south of Karachi, not far from the border with modern-day Pakistan at the mouth of the Indus. He sails a little further up the coast; nine months have passed since his departure from Aden. He wanders through the jungle and is bitten by a snake. He abandons his idea of sailing further to Ceylon, Sumatra and even the South Seas; he has reached his actual destination. Zitt is too emaciated to continue his adventure under sail.

He stays in Karachi for a while, stores his boat, visits Hindu temples and strolls through the city's bustling markets. Then he makes his way home to Europe. And he manages this journey too, travelling on various steamships, again without any money. He travelled as a stowaway, hired himself out as an assistant machinist and signed on as a burly Bavarian on an Arab dhow. He travelled the last stages of his journey by train. Rome, Milan, South Tyrol, Innsbruck. Until he is back on German soil and begins to write down his journey in the months that follow. Zitt is now 26 years old.

His book is published in 1937 and receives praise from the press and readers. His German Donnerritt is very much in keeping with the flavour of the time in the country. In 1937, the civil war was raging in Spain, the German Condor Legion aircraft squadron bombed the Basque city of Guernica and Picasso painted his famous picture of the same name. The Germans classify it as degenerate art, and in the same year they set up the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar.

Hardly anything more is heard of Hans Zitt after his sailing trip. He disappears into anonymity, vanishes into the dust of the looming world war. He could have returned to his boat, could have simply sailed on. But he probably lacked the exact opposite of his glorified iron will. A touch of poetry.

Also interesting:

Marc Bielefeld

Freier Autor