Portrait: Blue water pioneer Bobby Schenk - between adventure and Bavarian bourgeoisie

Ursula Meer

· 07.01.2026

When circumnavigator Bobby Schenk announces a "last time", you can never be quite sure. He has twice given up his bourgeois life as a lawyer in the civil service and sailed the world's oceans, only to throw on the gown again at some point in his Bavarian homeland. He announced several times that his popular blue water seminars were finally coming to an end, but there was always one more. This was also the case at the end of October 2025 at the Hanseatic Yacht School in Glücksburg.

The ambience alternates between sacred and maritime: the large hall, which extends into the gable, is decorated with sails and sail motifs. All the seats at three long rows of tables are taken. A good 150 sailors watch the speaker between the monitor and the lectern in front of a glass façade, through which the occasional ray of sunlight shines between the storm-shaken trees.

More on the topic:

Bobby Schenk has set off. Twelve Cape Horn sailors and 18 circumnavigators, including Golden Globe winner Kirsten Neuschäfer, will share their experiences with the audience. Later, he will retire and watch the events from the side of the hall, tired from the huge organisational effort, but also a little proud. First, however, he himself will talk about the quintessence of what he has sailed, learnt and developed - his "ten commandments", garnished here and there with little jibes at imitators, self-appointed experts and sailing magazines, including those present.

Seminar inspires and motivates

For more than 50 years, he has not only been active in the German-speaking long-distance boating scene, he has also significantly shaped it with books, articles and a - by his own admission gender-free - website with a huge number of hits. Above all, however, with lectures and blue water seminars that combine his accumulated knowledge and the experience of numerous long-distance skiers.

The participants at the long tables listen intently, as around 3,000 others have done before them in one of these 19 seminars. Not everyone here has cast off or will do so in the near future. One of them has been building his boat for 20 years. A young family doesn't quite know how to free themselves from all their obligations. And some just want to be inspired anyway.

Michael, meanwhile, has sailed around the world, and Uli is in the process of doing so. A good ten years ago, the latter attended one of the blue water seminars as a sailing novice and immediately got down to business, bought a boat and, after six months of preparation, cast off the lines together with his wife. They have now been sailing for two years and are permanently grateful for the boost the seminar gave them.

On the way, satellites plot the sailed route on the plotter and allow weather routings and dialogue with other sailors on the high seas. Their courses are already experienced in the literal sense by other sailors and destinations are described in detail. They are travelling with the adventure factor of an ever-present residual risk, but in a much more comfortable way than Bobby Schenk and his wife Karla experienced in the early 1970s.

Start into blue water life

"We had to acquire a whole lot of knowledge and skills, it was a full-time job," says Bobby Schenk, looking back on the time when the young couple dedicated all their free time to their shared passion for sailing alongside their first steps in professional life as a lawyer and pharmacist. They worked their way through the high school of astronavigation, sailing practice and seamanship and acquired various sailing licences on the local Chiemsee - Bobby for the high seas, Karla for the coast.

They were inspired by the adventures of Elga and Ernst-Jürgen Koch, German pioneers who returned from sailing around the world in 1967 and reported on their "dog life in glory" at lectures and in a book. The Schenks travelled from Munich to Hamburg especially to spend a whole day answering the Kochs' questions. The sailing literature of those days was limited, and "we realised that you need to know a lot more to sail around the world," says Schenk.

When they set off from the Mediterranean in 1971 in their small "Thalassa", a Fähnrich 34, they had a short-wave radio and a sextant on board instead of today's high-end navigation equipment, which would later contribute significantly to Bobby Schenk's fame. The pair travelled for four years. The fact that they crossed the Atlantic and eventually circumnavigated the entire globe on the trade route only became apparent en route. The young sailors, who until then had mainly travelled on inland lakes, slowly felt their way towards each new challenge between Beaulieu, Barbados and Bali.

Bobby Schenk's ten commandments of long-distance sailing

This is probably one of his most important recommendations: Start driving first, then plan. It's the sixth of Bobby's "ten commandments" and it puts paid to many an excuse for delaying a start. Other of his commandments also have what it takes to be a topic of discussion, for example when he places Austrian sailing training above that in Germany in terms of quality or states that jibing is not taught in training. This is probably why he said at the beginning: "I am no longer interested in discussions."

In his experience, compromises are out of place when choosing a crew, he adds. Sentences such as "I sail for the sake of my husband" are a guarantee for failure on a long voyage. At the time, Schenk was very lucky that his wife Karla, who died in 2018, was just as addicted to sailing as he was. "She was the perfect ship's wife," he tells his audience. When Bobby used to speak on the stages of large halls, it was she who stood at the projector in the background and threw the slides onto the wall. But there was more to her than that: "If you're afraid of everything, you spend your life behind the stove," she is often quoted as saying.

This kept them in civilian life for just five years after their first circumnavigation, Bobby in court and Karla in the pharmacy, before they gave it up again in 1979. With their second "Thalassa", they sailed to the South Seas again and dropped anchor off Moorea. They bought a house and land, wanted to accommodate guests and skipper them through the blue-green paradise, but business was slow. After four years, they grew a little weary of paradise. In his biography, Schenk describes "marrying Karla, planning life only for the medium term and being open to every twist and turn" as the best decisions of his life. So now he also initiated a change of direction and asked to return to the judgeship. This was granted and he had to return to Germany quite quickly.

Karla rejected his ideas of selling the "Thalassa II" in Polynesia and having it brought to Europe by freighter or with a paid crew - he wanted the voyage to end gracefully. So around Cape Horn. With terrifying images of unpredictable storms and lost boats before their eyes, the two avowed trade wind sailors set off on a long, "freezing cold" ride at the end of 1982 and sailed - around Cape Horn in moderate winds and calm seas - with just one stopover in Mar del Plata, Argentina, to the Mediterranean.

Bourgeoisie gives way to adventure once again

Their middle-class life had returned to them, but the spirit of adventure remained. So in 1989, they flew across the South Atlantic in a single-engine aircraft. This was actually an impossible undertaking, as the fuel in the tank was not enough to cover the distance. But Bobby spent whole nights calculating the influence of the trade winds on the flight route and came to the conclusion that the little plane could arrive in Brazil with a tailwind. It did, even with a few litres of petrol left in the tank. They sailed once more from Tierra del Fuego around Cape Horn before flying home in a long northerly arc.

A few years later, they sailed across the pond with a crew without a compass or any other navigational aids - only to land on Barbados with pinpoint accuracy.

When he finally retired, he travelled around the world again, now convinced of the benefits of sailing upright in a spacious catamaran. Since then, Schenk has also recommended that prospective long-distance sailors pay attention to the quality of living when choosing a boat, because "75 per cent of the time when sailing around the world you are in the harbour or at anchor. Sailing plays a subordinate role in the long run, the passion for sailing diminishes." A thesis that some of his sailing contemporaries might not agree with.

Sports journalist Christoph Schumann experienced them all as a YACHT editor in the 1970s/80s: Heide and Erich Wilts, Rollo Gebhard, Burghard Pieske and Wilfried Erdmann. "They were daredevils and had crazy experiences," he says of them, "Bobby Schenk, on the other hand, was more of a smart guy and preferred the barefoot route," he adds. The fact that he chose the less spectacular routes with Karla did not detract from his fame. On the contrary, Bobby Schenk awakened South Sea dreams with his pictures and words and showed that they were not only achievable for daredevils.

Schumann has attended many an event at the major boat shows with Bobby Schenk as a speaker or interview partner. "When Bobby was there, they were always packed to the rafters," he says. The smart Schenk was always good at putting down on paper what he had learnt and experienced on his travels.

His reports from the Pacific appeared in YACHT during his first circumnavigation, and his first book, "Fahrtensegeln", appeared in 1975. More than a dozen titles followed, each one a bestseller. They established the term "blue water sailing", translated from the English-speaking sailing community, in the German-speaking sailing scene, as well as a simple form of astronavigation.

Salt in the air

In the evening, everyone meets in the small bar of the Hanseatic Yacht School: rookies, charterers and circumnavigators. There's a little more salt in the air than usual on the Flensburg Fjord when they talk about their big plans or the stories that thousands of miles have written in their wake. They all learnt a lot or took the opportunity to experience the legendary Bobby Schenk once again at one of his equally famous blue water seminars.

And - was that really the last seminar? "Yes!" says Schenk, as it is always a huge organisational effort. What's more: "My wife has written to me threatening to divorce me if I carry on." His second wife Frauke, on the other hand, relativises: "Maybe there will be smaller events again." And who would know better than her about the restlessness of a Bobby Schenk?

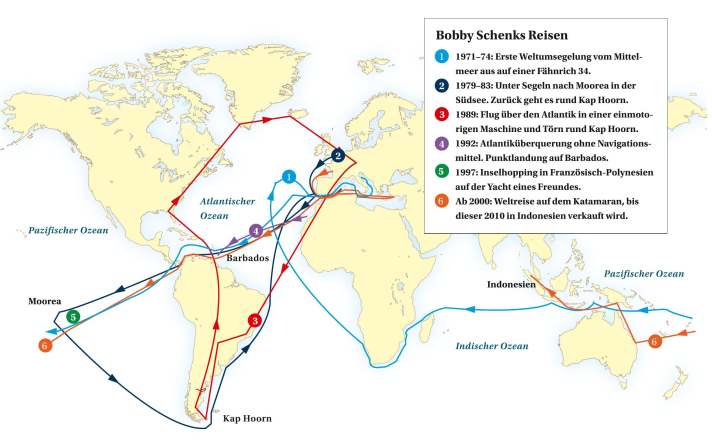

Bobby Schenk's travels

Astronavigation the outrageously simple way

With his penchant for navigation, Bobby Schenk took everything there was to learn along the way - including a previously unknown, simple method of astronavigation that the Briton M. J. Rantzen had written about. In 1975, he wrote an article about it in YACHT with the provocative title "Astronavigation for the weekend cruise". Readers wrote afterwards of an "end to the secret science", a "real aha experience"; others were annoyed that this form of navigation, which had been so respectful until then, should suddenly be practicable for everyone.

Schenk's book "Astronavigation ohne Formeln - praxisnah" is still in demand today. Together with the company Cassens & Plath, he also designed a sextant named after him. In the 1970s, Schenk, who had an affinity for technology and numbers, also developed an early form of electronic navigation. He created a pocket calculator module that enabled astronomical celestial calculations at the touch of a button and without the help of tables. This became "Bobby Schenk's Yacht Computer", which made life easier for many sailors on long voyages and only became less important with the advent of satellite navigation.