Text from Heide Wilts

At midday we leave the lagoon through the west entrance, and during the afternoon the wind turns a full circle: south-east-east-north-east-north-north-west-south. Welcome to the Indik!

We've been travelling for two days and two nights with strongly changing winds - sometimes too much, sometimes from the wrong direction, then calm again, and always the high southerly swell. In the Pacific I could blame El Niño or La Niña, but here it's just normal madness.

More on the topic:

5 July: A clear night with a full moon, in whose light you can read, brings a change! After an hour, it has turned into a half moon and after a few more minutes into a crescent moon. "This must be a lunar eclipse," Erich realises with razor-sharp precision. After an hour, the spook is over and the full moon is once again resplendent in the sky, as if it were none of his business.

Another three days have passed since then. The south-easterly wind has picked up to eight to nine Beaufort. Anxious question: will it stay this strong, where will it turn? With two reefs in the mainsail and the headsail furled to the size of a towel, the "Freydis" struggles through a chaotically foaming sea at six to eight knots. In addition to the wind, this is also due to the Ninety Degrees East Ridge, an inactive volcanic underwater mountain range that runs along the ninetieth degree of longitude to the east and rises steeply from a depth of almost 6,000 metres to between 2,000 and 1,000 metres, causing turbulence. A zone that demands a lot from us, especially as the wind is now blowing more strongly again and breakers are constantly coming into the cockpit.

After a few hours, everything in the boat is damp, clammy and uncomfortable. Both of us are subliminally seasick and lie down in the saloon - always ready to rush into the cockpit and steer by hand if the automatic steering system can no longer keep the boat on course. What she does is admirable! I pray that she holds out!

Will this perhaps be the end for me?

The ocean now hits us with full force and the wind sings its witches' song in the rigging. A quote from Robert Louis Stevenson comes to mind: "I have always feared the sound of the wind more than anything else. There would always be a storm blowing in my hell."

What a dreadful night! On board, the unpredictability of the world is experienced in fast motion. The hard knocks and the stumbling of the ship frighten me. The cans and bottles in the provisions lockers are pushed back and forth with a dull thump, back and forth ... Despite the noise, we try to relax, maybe even catch up on a little sleep to keep our strength up. I realise how my thoughts are slowly slipping away - home to my family, my friends, other places, worries, wishes, desires and into a restless sleep. Will this perhaps be the end for me?

Uproar of the elements! The spice rack above the cooker has crashed down. All of a sudden I'm wide awake again: 30 small bottles and tins are rolling around on the floor. It smells of vanilla and the contents mix with the oregano, granulated chicken stock and sesame oil from other containers. I need a whole roll of toilet paper to wipe the sticky "chutney" off the floorboards, although most of it ends up in the bilge anyway. After cleaning, I'm finally seasick and checkmated. Erich checks the sails and the course. "Everything's OK!" he hums reassuringly.

Once over the South Indian is enough - now we do it again

Like ghosts from the sea, memories of earlier sailing trips through the Indian Ocean - to the Comoros, the Îles Éparses, to Aldabra and Madagascar, to the Prince Edwards, Crozets, Heard, Kerguelen and St. Paul - rise up in me during my watch. Paul -, the severe storm in Crozet Bay with scenes that would have gone wrong by the skin of their teeth, the knock-down on the way from Heard to St. Paul, which was a shock for the whole crew; it suddenly made us realise our vulnerability and how serious our situation was in the incredibly high, murderous seas. Weeks later, on our arrival in Fremantle/Australia, I had shouted from the bottom of my heart: "Once across the South Indian is enough!", after this sea had truly given us nothing in the stormy forties and fifties.

And now, as if that wasn't enough, we cross it again - in the opposite direction and close to the equator, but here too it shows us its "heart of darkness": constantly high swells from the south, constantly changing winds in strength and direction, which constantly demand manoeuvres - in and out of the harbour, shifts, boom out.

Good seamanship involves anticipating certain situations, preparing for them in advance and thus avoiding unnecessary risks. There are few things worse than assuming in certain situations that "everything will be fine".

A wild animal in the storm

Sleeping is hardly possible, you toss and turn, no matter how many pillows you stuff around you. And during the day, all your senses are challenged, every movement has to be considered: Floors and stairs are like trapdoors, eluding your footsteps or pushing against them, and before you know it, the dining table in the cockpit is tipping a plate and meal onto your lap. No wonder the mind, stomach and spine rebel.

The boat behaves like a wild animal whose reactions you can't see through. Despite all the experience and a sixth sense that you have developed over time for its idiosyncrasies, you have to be constantly on your guard. You can steer the boat on a certain course, but otherwise your options are limited: You stagger, shimmy awkwardly and clumsily forward like a drunk, and simple manoeuvres become hard work.

The realisation that holding on to things cannot provide security can be experienced very practically on board. Nothing is safe here, nothing is secure, nothing can be relied on. Staying alive is everything. I've got used to that, there's no such thing as a risk-free life. I'm going to fall over on Rodrigues.

But I can understand Joshua Slocum when he writes: "But after all, where would the magic of the sea be if there were no wild waves on it?" For me, the sea is a last piece of unspoilt nature with its own laws and drivers - wind, current, tides. It breathes power, freedom, eternity, cannot be conquered, cannot be controlled, cannot be tamed.

Calm after the storm

The storm subsides in the morning. Towards midday there are still crests of water, but no whitecaps, no bite. The barograph has only scribbled its usual tropical curves during the storm. "We're drowning here and this expert doesn't even show the smallest jag!" I shout indignantly. Erich on the satnav, on the other hand, is delighted: "We've covered 151 nautical miles since yesterday lunchtime, and that's with the wind blowing before noon, which is the record of the trip so far!"

11 July, 8 p.m.: There are still 1,000 nautical miles to Rodrigues, i.e. about nine days. We celebrate the "mountain festival" with pizza and red wine, because we've reached the "summit" and are now counting down to Rodrigues, the smallest island in the Mascarene group. I finally want to read "Voyage à Rodrigues" by Jean-Marie Le Clézio.

Stars twinkle in the black-blue sky, the Southern Cross seems to be beckoning us. Two large right whales swim in our wake. We've seen something like this before in the Pacific. They keep a constant distance of two ship lengths, even though we are travelling at seven knots! Do they think we are their leader? Or are we pacemakers for them? On Erich's night watch, they disappear at some point.

No ship, no aeroplane far and wide, hardly any seabirds. Flying fish often land on deck at night, which we only find in the morning. Nobody wants to eat them for breakfast, as they used to on the Atlantic. I miss our onboard cats, Robbi and Adelie; they would appreciate the fish!

"Freydis" already senses the harbour

12 July: "I don't understand where the trade wind is," wonders Erich. "It seems like we've crossed its southern boundary." In fact, we were pushed southwards by the frequent wind shifts.

We resolve to get the boat back on course and avoid this mistake in future by quickly adjusting the sail position in the event of wind shifts and gusts. It's a tough job, because the person on watch is constantly under strain in the changeable weather and has to wake his partner if necessary. For days now, we have never slept for more than two hours at a time.

19 July: The counter-steering paid off: we are back on a direct course to Rodrigues. The Mascarenes were already marked on medieval nautical charts of the Arabs, on whose trade routes from East Africa and Madagascar to the Arabian Peninsula to India and Indonesia they lay. They were later given their European names by the Portuguese after Bartolomeu Dias found the sea route around the Cape of Good Hope in 1486 and Vasco da Gama found the route to India in 1498. Portuguese merchant ships also visited the islands to stock up on fresh meat and fruit. Later came the ships of whalers, pirates and the Dutch East India Company. And now we are curious to see what has become of the islands. Detailed maps are on the table.

The "Freydis" already senses the harbour and is in a hurry: despite her reduced sails, she gallops across the choppy sea. Turning both ways is not an option, nor is taking the genoa away completely: with the breakers, the sea is far too rough for that. It's better to get under cover quickly and wait until it gets light.

At two o'clock in the morning we have Rodrigues on the radar at a distance of 14 nautical miles. A little later, its lights can be seen with the naked eye, but keep disappearing behind heavy rain squalls. At four o'clock in the morning we turn to leeward of the island.

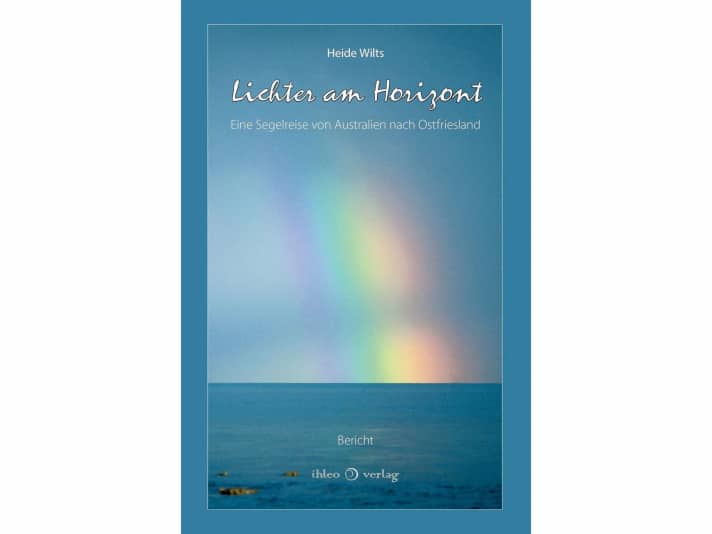

The book: "Lights on the horizon" by Heide Wilts

With her latest book, Heide Wilts completes the series about all the voyages to the remotest corners of the earth sailed with her husband Erich, who died in 2022, from 1969 to 2021. The Wilts left more than 350,000 nautical miles in their wake. Ihleo Verlag, 25 euros.