On most yachts today, the current location of the ship is provided by the global navigation satellite system (GPS) - anytime, anywhere and regardless of weather and visibility. Conventional positioning methods, which were used in the days before GPS and are still asked in driving licence exams, are often forgotten in everyday life on board. However, observations regarding possible GPS signal interference in the vicinity of crisis areas are bringing tried and tested terrestrial methods back into favour.

Even in supposedly safe climes, circumstances can occur - such as water ingress or a lightning strike - that render the navigation electronics unusable, meaning you have to revert to traditional methods. Quite apart from that, there is always a certain charm in finding out where you are by simple means, just like the sailors of old. We present the most important methods here; if you want, you can delve deeper into the subject in other articles (see below).

Determining location by taking bearings

To determine a location, objects with a known position must be in view. This also applies to satellite navigation, where the GPS antenna must have a sufficient number of satellites in its field of view. In terrestrial navigation, these objects are earthbound, such as navigation marks and landmarks. They must also be recorded on the nautical chart.

The first step is therefore to look out of the cockpit: what can be recognised in the ship's surroundings and which of the objects discovered can also be found on the nautical chart? Is the prominent church tower on the starboard side actually on the chart? What about the radio mast recognisable further ahead? In order to be able to recognise it without any doubt, you need to have at least a rough idea of where you are - regular docking helps here.

Some nautical charts and sailing guides show drawings or photos of distinctive landmarks as an aid to identification. The appearance of lighthouses is also described in the lighthouse directory. At night, beacons can be clearly identified by their colour, identification and return.

As a general rule, the more orientation points are included in the location determination, the more reliable the result will be. However, there will not always be several suitable objects in view at the same time. Especially as these must be objects with a fixed position. Bins floating in the water are only suitable to a limited extent. Ultimately, however, you have to live with what is there. Inaccuracies can be corrected if more suitable objects come into view.

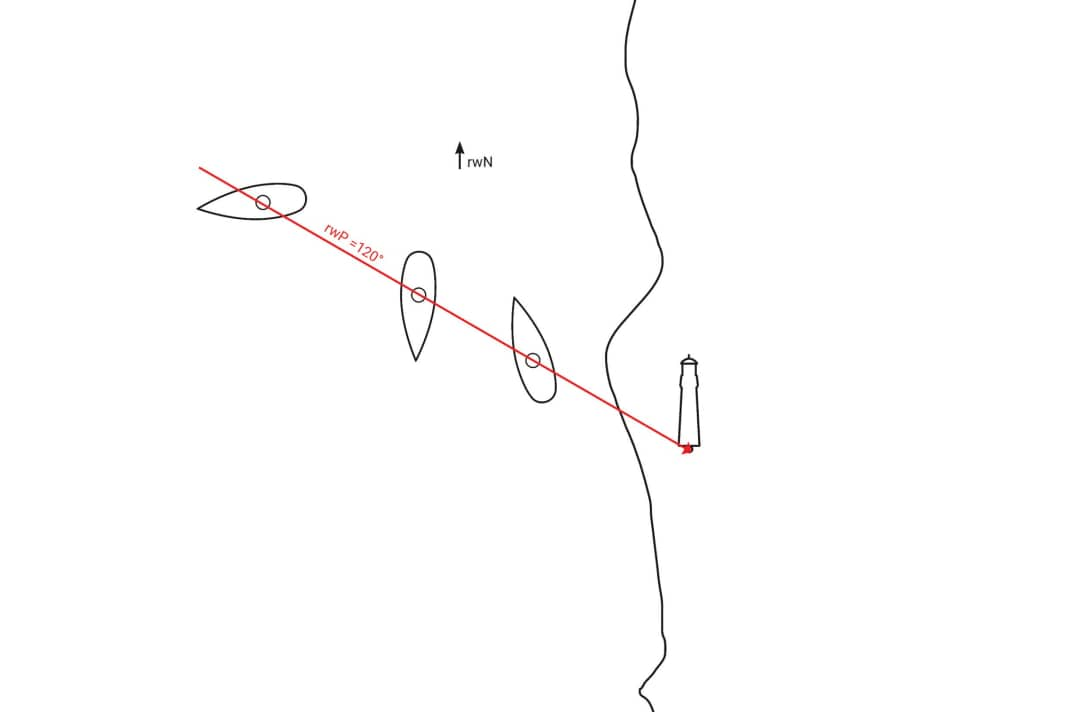

Cross bearing and bearing lines

The easiest way to determine a location is to take a bearing. For example, if you take a bearing on a lighthouse at 120 degrees, you must be somewhere on a line from which the lighthouse lies exactly in this direction. This is known as a bearing line. It includes all possible ship locations based on a previous measurement.

The bearing line is entered in the nautical chart by drawing a line in the opposite direction to the bearing (bearing value +/- 180°) starting from the location of the lighthouse. For example, if the lighthouse is at 120 degrees from my point of view, I must be at a bearing of 300 degrees from the lighthouse.

It is important to always use the true bearing (rwP) for entries in the nautical chart. This is because the nautical chart is orientated to true north (rwN). On sailing yachts, however, bearings are usually taken using a magnetic compass, which is subject to so-called compass errors.

A magnetic compass bearing (MgP) must therefore first be corrected for the deflection (Abl, also deviation) and the magnetic variation (MW) and converted into a true bearing. You can read how to determine the values for this in this article.

After entering the bearing line on the chart, we already know that we are somewhere on this line. For a location, we need at least one more bearing line - ideally from a second bearing object. The ship's location lies at the point of intersection.

For such a cross bearing, the two bearing objects should not be too close to each other, otherwise the lines will overlap so that no clear intersection point can be seen. This is referred to as a "dragging intersection", which also occurs with opposite bearing objects. If possible, the angle between the two lines should be more than 30 degrees and less than 150 degrees.

Deepen your knowledge:

You can find out more about cross bearing and other bearing methods, such as cross bearing and four-line bearing, bearing with only one object or distance bearing as well as sounding in this article.

Dead reckoning

The dead reckoning method is simple. The yacht's movement, deduced from its course and speed, is transferred to the nautical chart to determine where it should be at any given time. This is done by plotting the course steered since the last known location of the ship. The distance travelled since the last location was determined is plotted on this course line. Its length results from the logged speed in relation to the elapsed time.

The result is the so-called coupling location. It is generally labelled with a horizontal line on the course line and the abbreviation "OK" (an observed location, on the other hand, has the abbreviation "OB" and is circled). The current time is also entered so that it can be used later for further coupling.

The methods and formulas used for pairing are also suitable for making predictions. For example, advance coupling can be used to determine when you will arrive at your destination or the next waypoint. This Estimated Time of Arrival, or ETA for short, is calculated from the distance to the destination in relation to the speed of the yacht.

Deepen your knowledge:

Further topics in connection with coupling, such as the offset of the mount, the calculation of misdirection and deflection, advance coupling and co-coupling, as well as an alternative in the event of a logger failure, are discussed. in this article comprehensively treated.

Wind and flow influences

Following a given chart course on the water can be quite a challenge. After all, boats don't always sail in a straight line.

The course setting ensures that the bow points exactly in the direction of the target. Nevertheless, the yacht can change course over the ground if it is shifted sideways by the wind and current.

In order to find out where this lateral offset is taking them and how it can be compensated for by holding ahead, the course charging must be extended. In the case of wind drift, this primarily requires experience, while nautical documentation helps to determine a tidal current offset.

The wind-induced drift can often only be estimated. After all, it depends on many factors, such as the type of boat, the wind force, the current sails, the lateral plan, the heel and the correct trim.

Another factor is the course to the wind: while there is naturally hardly any lateral drift to be expected when sailing flat in front of the sheet, it is all the more noticeable on an upwind course.

Deepen your knowledge:

Taking wind and current influences into account is one of the more difficult disciplines. In tidal areas in particular, however, feeding the current is very important for the above-mentioned methods to make sense. In this article you can find out everything you need to know.

Careful trip planning

Conscientious route planning begins long before the start of the trip and should always be adapted to the current situation after departure. Navigational trip planning takes place on three levels: at home in the run-up to the trip, on board before setting off and at sea.

Planning at home

The first phase of navigation begins weeks before the start of the trip. The first step is to obtain useful information and documents about the area. This can be information from the Internet or from magazine articles - for example Travel and area reports, cruise and stage suggestions and the like. On the other hand, researching suitable nautical documents is important for safe navigation.

With a view to safe navigation, the selection counts suitable nautical charts and from Area guides and harbour handbooks are among the most important preparatory measures. You should always purchase these documents yourself, even for charter trips. The manageable investment is offset by an immense benefit, as this is the only way to ensure reliable planning.

You should familiarise yourself with all the peculiarities of the area at home using the maps you have purchased: Distances, depth courses, traffic routing, navigation restrictions due to restricted, nature conservation and traffic separation areas, bridge or lock passages and so on. Initial notes can be made on possible stages and special navigational features.

The result of this preliminary planning is a list that outlines a complete itinerary with all the stops over the entire duration. This list outlines the ideal itinerary, so to speak, and takes into account both the desired destinations and all the essential seamanship aspects based on the information available.

Planning on board

The final roadmap should be finalised on board immediately before the start of the trip. Then you can inspect the yacht in detail during a charter trip, know its possibilities and limits and have obtained the latest information on the weather and sailing area. All this enables a final reality check.

Planning at sea

During the entire course of the trip, it is necessary to react flexibly to changes, as not all factors are known in advance. The weather in particular is continuously monitored and documented in the logbook (air pressure, temperature, humidity, cloud cover, wind direction and wind force). This data helps to understand the current weather conditions and assess possible local effects.

In addition to the weather, numerous factors can influence the cruise plan, such as technical problems, health problems of crew members or supply bottlenecks if fuel becomes scarce due to a lack of wind.

Deepen your knowledge:

There is still a lot to say about these aspects, which we in this article have compiled.