The passage of Cape Horn is the southernmost point of the regatta, the most current-intensive, with a strong ice presence due to the proximity of Antarctica and strong winds that make navigation difficult. It is not for nothing that the passage is feared by sailors; the Cape Rounding is considered a notch in the colt of every circumnavigator. In view of the gigantic dimensions, it is almost a miracle that not much more was broken during this Vendée Globe.

More about Cape Horn:

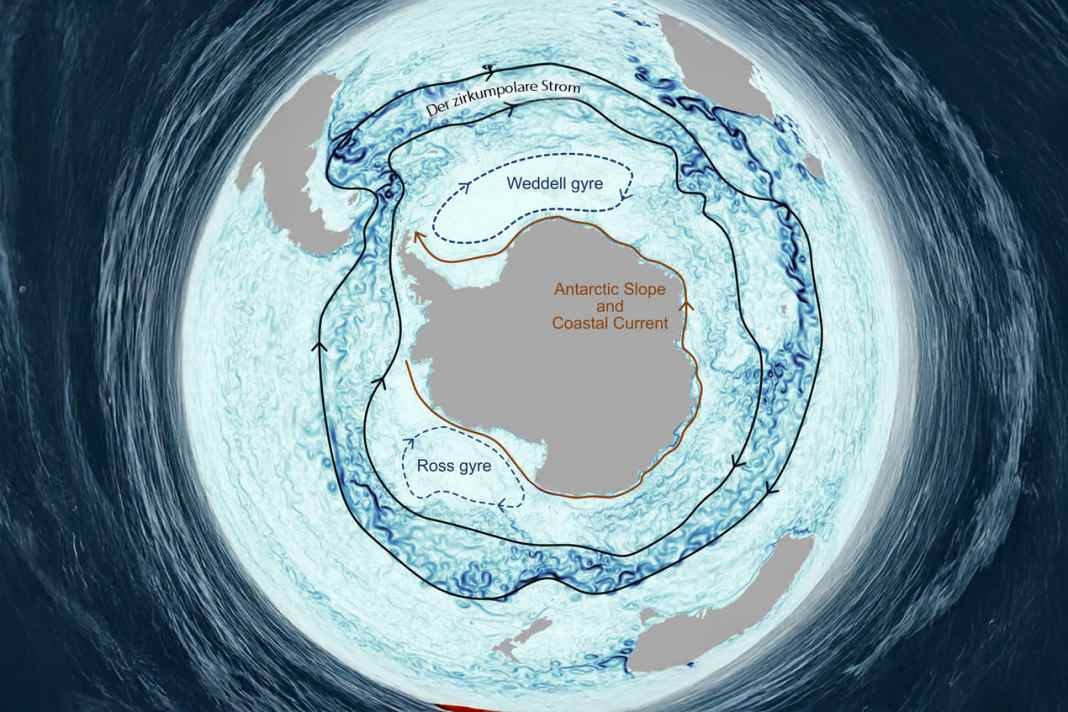

110 times stronger than all rivers combined

The circumpolar current washes around the Antarctic and carries the Vendée Globe skippers in their race around the South Pole. "It is the strongest of all ocean currents because there is no land obstacle to stop it," emphasises Clément Vic, researcher in physical and space oceanography. "It is strongest south of Cape Horn: the South American tip and the Antarctic Peninsula form a kind of bottleneck, the so-called Drake Passage, which has an accelerating effect on the current. The volume of water flowing through it is estimated at 170 million cubic metres per second, which would be around 100 times greater than all the world's rivers combined."

A trap 700 kilometres wide

In this 700-kilometre-wide geographical bottleneck, there is no escape for sailors from low-pressure areas, which can be up to 1,000 kilometres in diameter. This is in contrast to other shipping in the southern hemisphere, where they can avoid storms in the north or south. In addition, this passage is particularly dangerous due to icebergs or other broken pieces of ice that are not necessarily detected by satellites.

Huge conveyor belts

The world's oceans are in motion. The wind creates the waves, the moon and the sun cause the tides, the earth's rotation creates whirlpools. And to add the vertical dimension, the cold and salty water plunges into the depths. A huge oceanic conveyor belt thus transports every drop of water around the world, from the surface to the bottom and from the bottom to the surface.

Open questions

Clément Vic on the scientific questions he still has about this fluid mechanics: "We know relatively well how the water sinks to the bottom, but we know less well how the water rises to the surface. The interactions between the currents and the seabed create turbulence and certain places where the water rises. Our recent studies show that the rise of water droplets depends on the topography; on reliefs such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, for example, the water rises in several places".

What do the currents mean?

Why is it important today to better understand the dynamics of ocean currents? Because they have a decisive influence on our climate. The best-known current, although not the strongest, is the Gulf Stream, for example, whose extension, the North Atlantic Current, transports mild temperatures and moisture to Europe and explains why we do not have a Canadian climate on our coasts.

However, climate change is disrupting the ocean currents. Melting ice, for example, is intensifying and accelerating the flow of fresh water at the poles with less salty, lighter surface water. How will our conveyor belt react in the coming decades? Is there a risk of it getting stuck? To answer this question, scientists are using measuring instruments in all the world's oceans, for example with the Argo floating net. They also use surface observations carried out by satellites equipped with sensors. Finally, they use computer calculations to solve the equations that determine the movements of the oceans. This enables them to predict how the climate could develop by 2050 or 2100.

The ocean as a heat reservoir.

Compared to the atmosphere, the ocean is a significant heat reservoir. Water can absorb thousands of times more energy than air. The ocean therefore functions like a sponge, absorbing excess heat from the atmosphere and 25 per cent of the CO² emitted by human activity.

Scientists warn that a further acceleration of the current due to current global warming could lead to the Southern Ocean storing less CO² and more heat reaching the Antarctic.

Lars Bolle

Chief Editor Digital