In this article:

All boats with a propeller under the hull have it, the so-called wheel effect. It varies depending on the type of drive and the shape of the hull, but is always present. The effect causes the stern of the boat to move sideways when starting off. It can be used deliberately for manoeuvring and can make some starts and stops very elegant. Rowers who ignore it, on the other hand, sometimes break out in a sweat.

Knowledge of the wheel effect is a must for every skipper. Especially when it comes to an unfamiliar yacht, such as when chartering, you should know the effect in order to position the boat accordingly during harbour manoeuvres.

The correct term is actually propeller effect, as it is caused by a phenomenon on the prop. However, the term wheel effect has prevailed, as this describes the effect and is more intuitive. This is because the propeller can be imagined as a wheel that touches the ground and runs along it.

When travelling astern, the wheel effect is much more pronounced than when travelling forwards

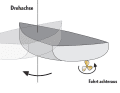

A right-turning propeller, as on most modern yachts, runs to the right over the bottom and pulls the stern to the right. In reverse, when the prop is turning anti-clockwise, the same thing happens, only to the left. When travelling astern, the effect is also much more pronounced than when travelling forwards, which is why reversing is considered first in the following. The drawings on this page are also designed accordingly.

The wheel effect with U and S frames

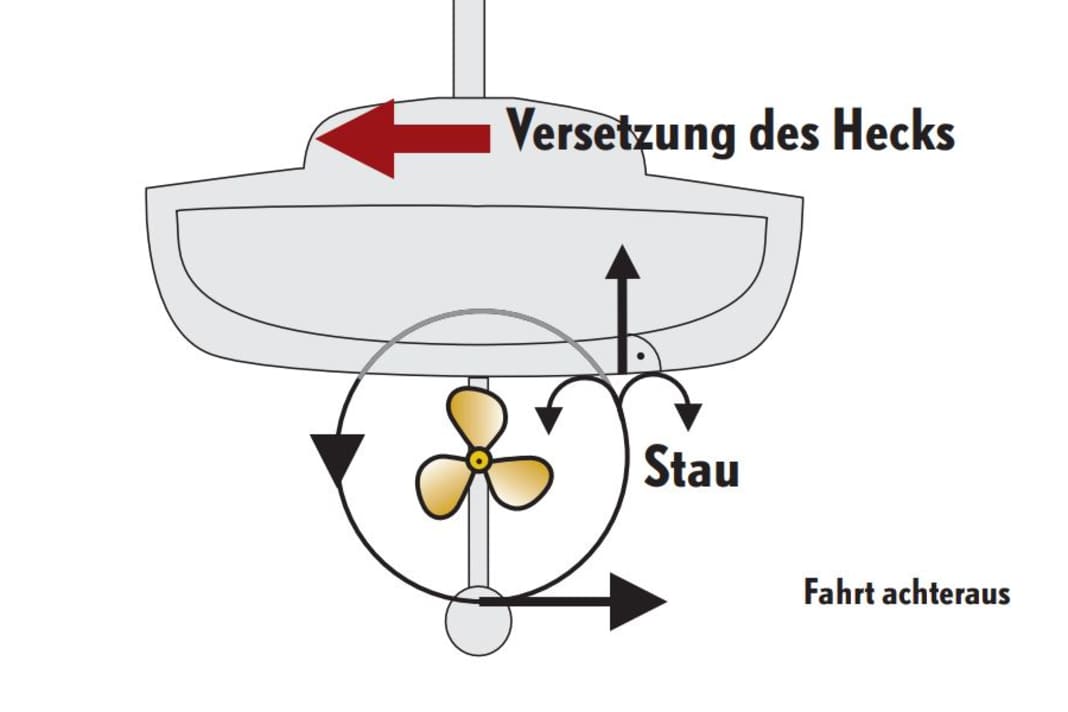

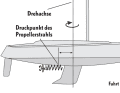

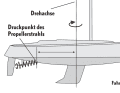

The wheeling effect is caused by a build-up of water under the hull. The hull of the boat acts as a kind of lid that prevents the water from being transported evenly. Without the hull, i.e. on a free-standing propeller, the blades would transport the same amount of water at every position during their circular movement. So with a propeller turning anti-clockwise in reverse, the blades would move downwards on the left-hand side, upwards on the right-hand side, to the left on the top and to the right on the bottom. However, this even transport is hindered by the hull. Put simply, the blades throw the water against the hull as they move upwards. There it accumulates and exerts pressure on the hull.

This does not affect the current on the underside of the prop. It therefore constantly shovels water to starboard. Negative pressure is created on the port side, which pulls the stern along. Overpressure is created on the starboard side. The steeper the hull shape, as with an S-frame, the more it obstructs the propeller flow. It then no longer hits the hull vertically, but at an angle, exerting greater pressure. If it is also a long keel boat, where the prop works in a tunnel, the keel acts like a separating plate. The prop can only move water from one side to the other and the wheel effect is very pronounced.

The wheel effect with different drives

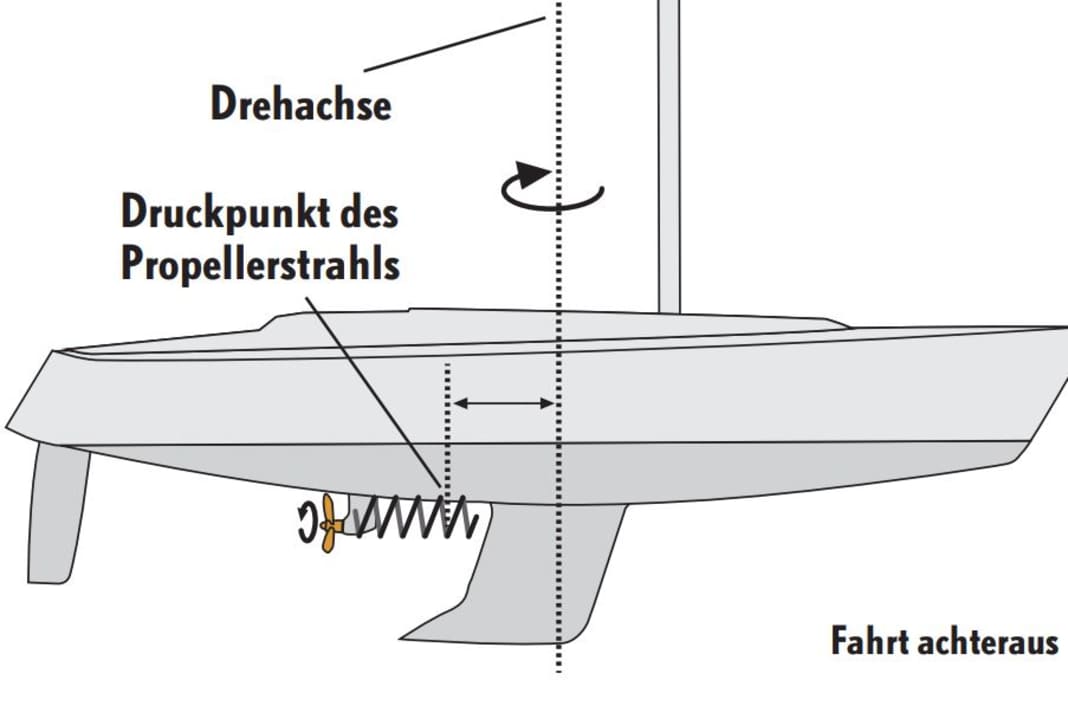

However, the type and position of the drive also have an influence on the strength. The further away the propeller is from the axis of rotation of the boat, the greater the torque it can exert. For example, a yacht with a shaft drive will always have a stronger wheel effect than a comparable boat with a saildrive, as this is much closer to the axis of rotation.

In addition, with a saildrive, the prop is positioned vertically in the water and the propeller jet is therefore directed horizontally away from it. However, with a shaft system that is normally inclined by around 15 degrees, the propeller jet hits the hull at the same angle from bottom to top, which increases the stalling effect.

This means that modern yachts with a flat U-frame and saildrive normally have a much less pronounced wheeling effect than older S-spans or even long-keelers. With the latter, the effect can even be so strong that travelling astern becomes impossible. The prop then pulls so strongly to the side that the usually small rudder behind the keel cannot counteract it. In such a case, the only thing that helps is to correct the course with short forward thrusts, as shown in the diagram on page 76.

There are also several reasons why the wheel effect is stronger aft than ahead. For example, the propeller jet hits much less hull surface when travelling forwards. The prop is mounted at the rear, where the hull ends. In addition, it does not reach as deep there and can therefore interfere less with the propeller flow. The most important reason, however, is the rudder. With thrust ahead, the propeller is already flowing against it when stationary, generating corresponding pressure and counteracting lateral drift.

In contrast to reversing, the type of propulsion has hardly any influence on the strength of the wheel effect. As mentioned, the prop on a yacht with a saildrive generates a relatively low angular momentum anyway due to its proximity to the axis of rotation. This is stronger with a shaft system. However, as the prop sits directly in front of the rudder, the full force of the propeller current hits the blade, and the effect can usually be compensated for by a slight rudder angle.

Countermeasures are usually intuitive

Fortunately, this counter-steering against the wheel effect is intuitive and usually does not require much practice. If a course change to port is required from a standstill, the wheel effect supports this, as the prop turns to the right when engaged and thus moves the stern to starboard. Only a small amount of rudder needs to be applied. However, if you want to move to starboard, the wheel effect has the opposite effect. This means that considerably more rudder is required. The only thing that takes some getting used to is starting straight ahead with a stronger wheel effect. A little rudder angle to starboard is then necessary.

As the examples in this article show, the wheel effect can simplify manoeuvres such as mooring alongside a pier. However, it can also make manoeuvres impossible, such as turning in a confined space, if the wrong side of the yacht is chosen. Every skipper should therefore be aware of this peculiarity of their boat in order to incorporate it correctly into their manoeuvre planning.

It is a good idea to practice in an open harbour area or in calm weather outside the harbour with a fender as a reference object: Accelerating from a standstill astern, full circles forwards and backwards and stopping are all you need to do.

The wheel effect when manoeuvring

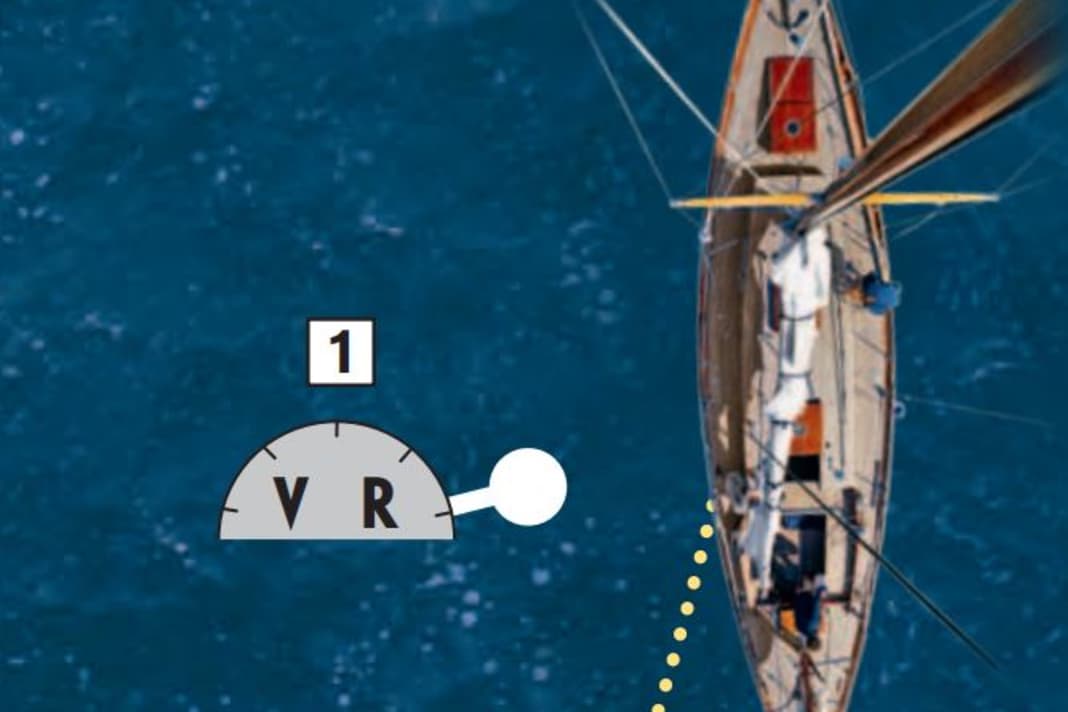

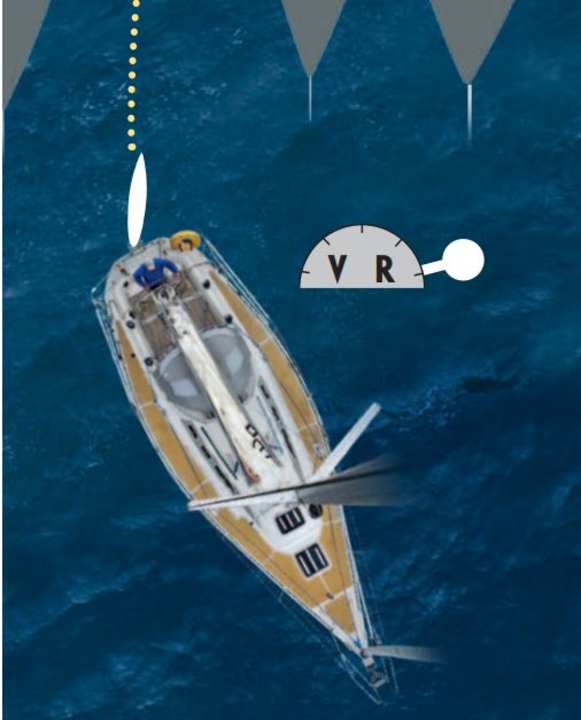

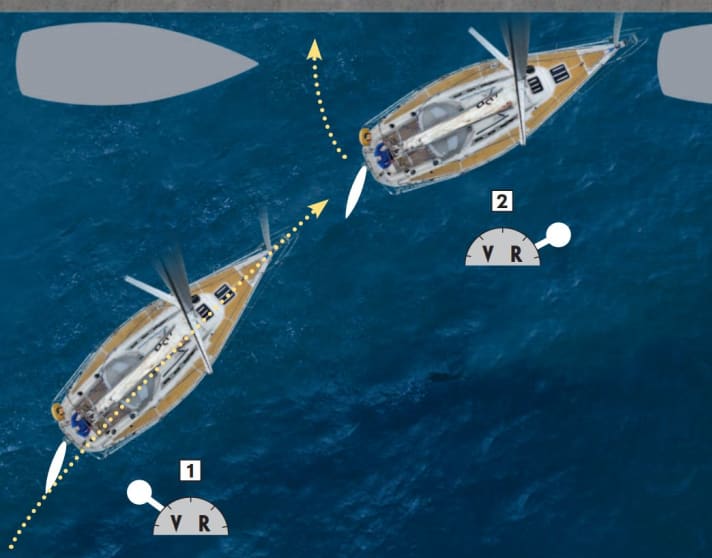

Keep on course with speed astern

Engage ahead without rudder action

Retention

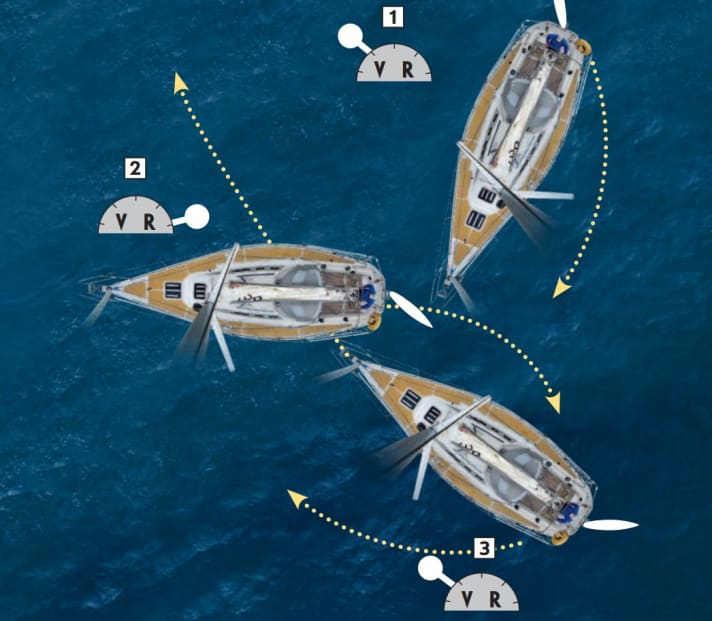

Turn over the right side

The effect helps when turning to the right side

- The turn over starboard is initiated with thrust ahead and rudder angle

- When stopping, the rudder effect moves the stern further to port and thus supports the turn. As soon as the yacht picks up speed, the rudder can be moved to port if it is effective. Otherwise, leave it turned to starboard

- A strong thrust ahead on hard to starboard ends the turn. As soon as the yacht picks up speed, ease off the throttle

Turn over the wrong side

- The helmsman wants to turn on the port side. A short thrust ahead and the remaining speed push the stern round

- When stopping, the left-turning propeller generates a strong wheeling effect to port, which the rudder cannot fully counteract. The stern turns back to port

- Although the new thrust ahead turns the yacht slightly in the right direction again, it is not enough to turn. The constant rocking back and forth moves the yacht to leeward until the manoeuvring space runs out. The manoeuvre fails

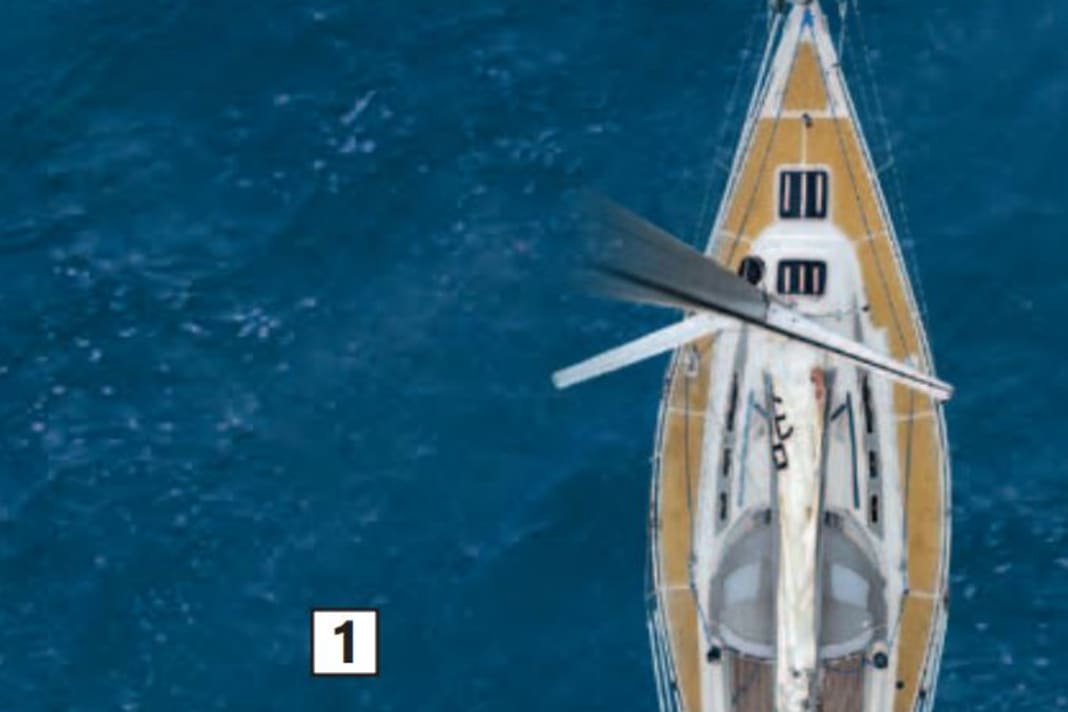

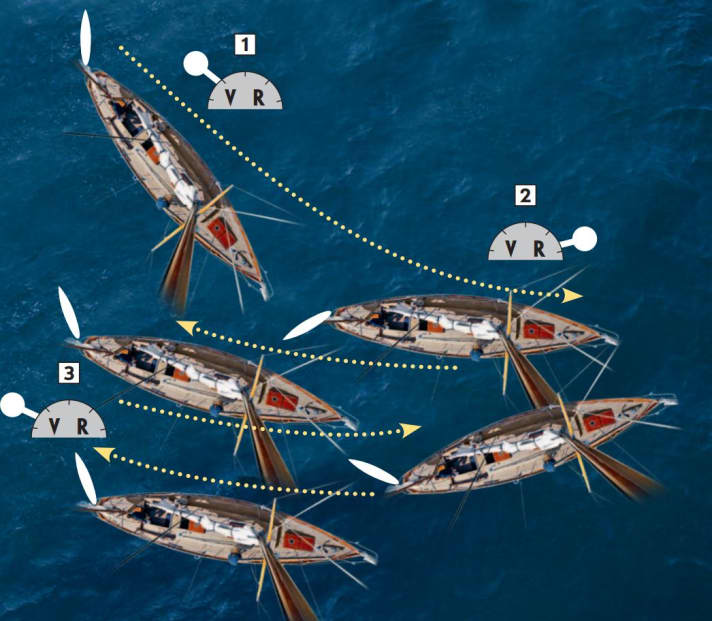

Longside mooring at a pier

- Anchor off the port side. Approach the berth at such a speed that the yacht is still easy to manoeuvre in the prevailing conditions. Aim for the end of the gap in a slight arc

- Brake the yacht with a strong thrust astern just before reaching the pier, paying attention to the braking distance. The wheel effect will move the stern to port and pull it gently towards the pier. Ideally, the yacht will come to a standstill when it is parallel to the pier and the crew can comfortably go ashore