All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios

If a crew member fell overboard, the sailor of yore would shout: "Man overboard". Today, the official and politically correct term in terms of gender awareness would be "person overboard". However, as this is not easy to say in an emergency, sailors have switched to "man overboard". This is also gender-neutral, but can be abbreviated to MOB in the same way as the traditional "man overboard".

Regardless of the correct term, it is every sailor's nightmare: a crew member goes overboard. Frighteningly quickly, the person is left in the wake, even if the crew reacts quickly and initiates a rescue manoeuvre. The biggest concern at first is losing sight of the person in the water. Only the head of a floating person peeks out of the water - very little to make them out in choppy seas. However, the more time the search takes, the more the casualty cools down.

Communication barriers can be overcome if everyone knows what to do in an emergency and hand signals have been agreed. There is also a precise distribution of emergency roles: Who takes the lookout and shows the helmsman the way, who starts the engine, who makes the emergency call, who releases the sheets at the right moment?

It's best to schedule a practice session every season. If the crew makes time for it, it is guaranteed to be an exciting day - which gives everyone the good feeling of being prepared for an emergency. But the most important tip remains: Pick up and put on your lifejacket!

The right manoeuvre can save lives

Which manoeuvres are the most effective for returning the yacht as quickly and safely as possible to a fellow sailor who has fallen overboard? We tried out various manoeuvres at sea and discovered some amazing things.

There is no such thing as the ideal MOB manoeuvre that can be applied to every emergency scenario. Wind, waves, crew strength and type of ship all have an influence on which manoeuvre is the right one. However, the following always applies in dangerous situations on board: the skipper and crew must know their yacht. How does the ship behave in currents or strong waves, how does it steer under engine power, can the sails be operated single-handed in an emergency? This only works with practice, and even the experienced regatta helmsman sometimes finds it difficult to sail a precise shot close to someone who has fallen overboard. That's why the skipper and crew should not only consider the question of which rescue manoeuvres can work in theory before their first stroke and clearly assign the roles in the event of an emergency.

Control during the MOB manoeuvre

If a crew member goes overboard, speed is of the essence. The ship must return to them quickly and safely. In some MOB manoeuvres, it therefore helps to use the engine for support. In a manoeuvre under pure engine power, the sails are recovered immediately after falling overboard in the wind and the engine is started. The boat is then turned and driven back to the scene of the accident. The boat is stopped next to the casualty and immediately disengaged so that no injuries can be caused by the propeller. The advantage of such a manoeuvre is that the sails no longer provide a surface for the wind to attack and the ship drifts less strongly. However, as the crew is initially occupied with hoisting the sails, there is a risk that the casualty will be lost from view.

This is why we recommend always starting the engine as well. It helps with steering, stopping or not losing speed too early on the last few metres.

If in doubt, all sheets can simply be cast off and the boat can be motored alone. In this case, however, the crew must be extremely careful not to be hit by a sheet that flaps around or even by the main boom swinging back and forth.

The last section to the person in the water is the most critical. There must be sufficient speed in the ship, but the casualty must not be run over under any circumstances. Steering is made more difficult because the helmsman can no longer see the head of the co-sailor as soon as he is close to the side of the boat.

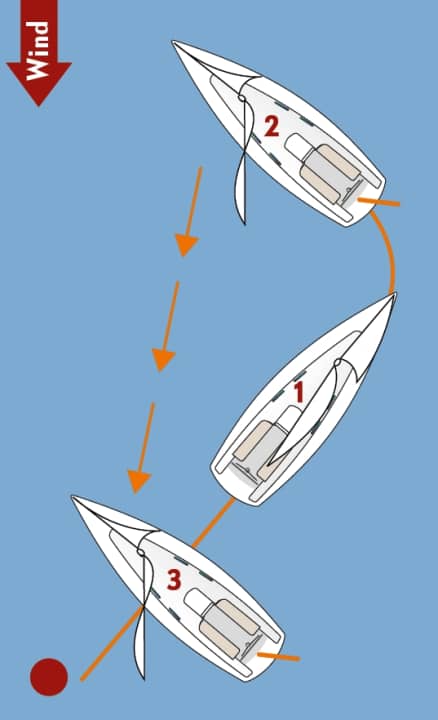

MOB manoeuvre 1: Munich manoeuvre

If a person goes overboard on an upwind course, tack quickly, keeping the jib astern. The main is unfurled wide and the rudder is turned to luff in order to drift towards the person who has gone overboard. The manoeuvre is suitable for single-handed sailing, but requires quick action, practice and knowledge of how the yacht drifts. If it drifts past the casualty, a gybe or Q-tack must follow to get back to him - that takes time. Forward and reverse thrusts with the engine help to arrive at the right point. So here too: Start the engine and keep it running!

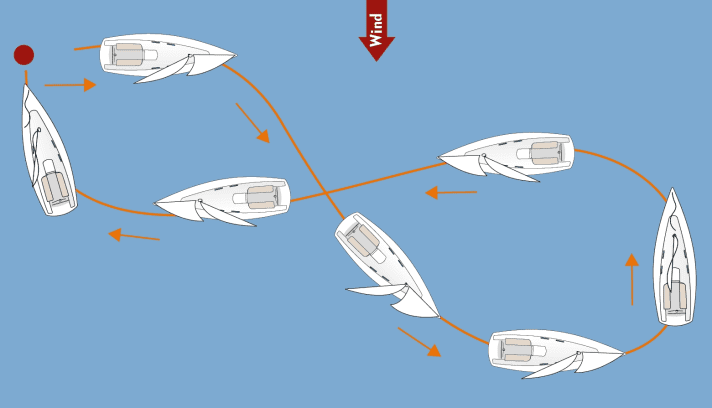

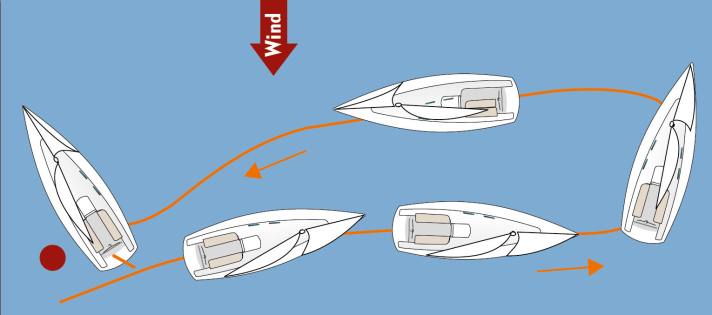

MOB manoeuvre 2: The Q-turn

The classic rescue manoeuvre under sail. Also rely on engine support here. The Q-shaped course, which gives the manoeuvre its name, avoids a gybe. If a person has fallen into the water, drop off immediately to gain depth. Then tack and sail back to the person in the water with half the wind. This is followed by a near-jibe so that the person is reached. Advantages of the Q-turn: Even without the aid of the engine, the boat always maintains speed. It can also be sailed from different starting courses. Disadvantage: When falling off, you are relatively far away from the casualty, so a crew member must keep a constant eye on the person overboard. At the same time, the helmsman needs information about the direction in which the MOB is moving in relation to the ship in order to be able to adjust his rescue course accordingly under sail or with the help of engine power.

MOB manoeuvre 3: Under machine

In many MOB manoeuvres, it helps to start the engine as a backup. In this variant, the sails are recovered in the wind immediately after the person has gone overboard and the engine has been started. As soon as the sails are down, you return to the casualty and stop next to them. Then disengage the clutch to avoid injury from the propeller. The advantage of this manoeuvre is that the sails are not killed when the person overboard is rescued and the boat drifts less. However, the crew's attention is focussed on taking in the sails beforehand, meaning that the drifting boat may drift out of sight. For this reason, a variant in which the genoa is only quickly furled may be more sensible.

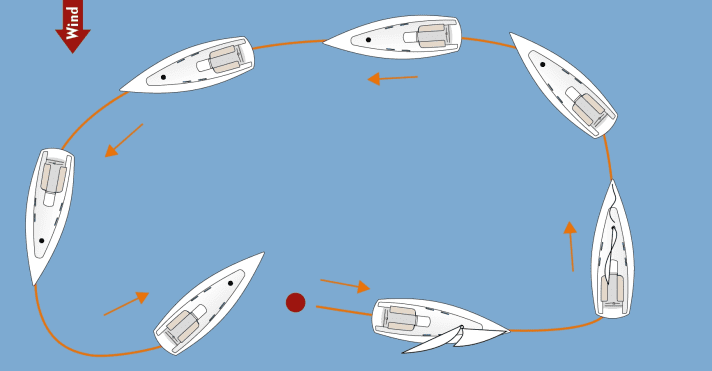

MOB manoeuvre 4: The quick stop

If a sailor falls into the water on a fast downwind course, there is a particularly high risk that the yacht will quickly drift far away. To prevent this, the yacht is immediately tacked hard during the quick stop to put it into the wind - regardless of how the sails are set, even under spinnaker. The engine is then started and returned to the MOB. The disadvantage of this manoeuvre is that the sails flap violently, increasing the risk of injury on board. In addition, the boat is almost impossible to control during this manoeuvre without the engine.

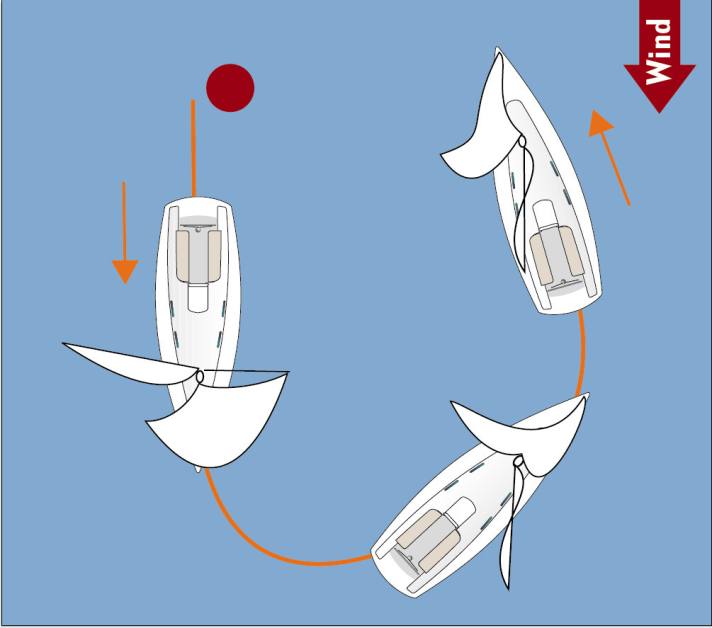

MOB manoeuvre 5: The Hamburg manoeuvre

After falling overboard, the yacht initially continues on a half-wind course, then turns and sails back to the MOB with half the wind. At the tack, the jib remains back to reduce speed. Shortly before reaching the MOB, we tack until the boat is almost stationary. The mainsail remains tight, creating a heel to leeward. The freeboard is reduced and the person can be taken back on board more easily via the leeward side. Advantage of the manoeuvre: As the jib does not need to be operated, it is also suitable for a small crew. Disadvantage: In heavy seas, as with the Munich manoeuvre, there is a risk of the yacht drifting too far towards the MOB. The manoeuvre procedure is the same as for the mooring manoeuvre.

The best videos about the MOB manoeuvre

All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios