Vendée Globe: 50 per cent increase in performance - the incredible development of the Imocas

Max Gasser

· 01.11.2024

Since their beginnings in the 1980s, Open 60s have stood for innovation like no other offshore class. The development has been enormous, especially in the last ten years. A study around a year ago illustrated the obvious in figures. After the rapid progress, however, there is now a feeling of a performance plateau. So will there be no new records at the tenth edition of the Vendée Globe starting from Les Sables-d'Olonne on 10 November?

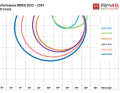

For the large-scale study, sailor and performance expert Olivier Douillard analysed and compared the measured values of the best boats of all Vendée Globe generations since 2002. The Frenchman's company, AIM45, specialises in data analysis in regatta sport, wind turbines and cargo shipping.

Imoca development: 50 per cent increase in performance since 2002

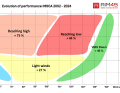

The result of his analyses: an increase in performance of almost 50 percent in the period studied! In addition to a significant improvement in top speed in almost all conditions and on almost all courses, there is another remarkable trend: the wind force required to reach a boat speed of 20 knots has dropped significantly over the same period. Whereas 20 years ago it took 30 knots, today only 14 knots of true wind are needed to achieve such speeds with an Imoca.

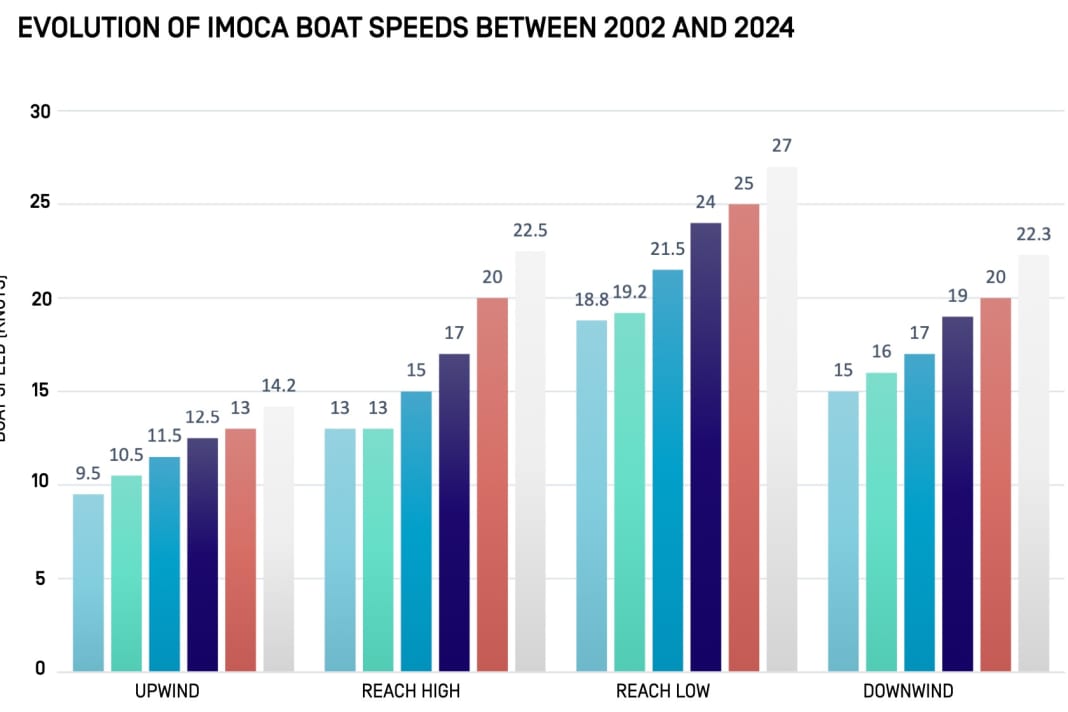

Upwind, the average boat speed has increased from 9 to 14 knots since 2002, and downwind from 15 to 24 knots - 49 per cent in each case. According to Douillard's study, the result is even clearer on half-wind courses. Here, the latest foilers achieve a 73 per cent higher speed.

In addition, the Imoca 24-hour record in 2002 was 467.7 nautical miles, while Team Malizia set a new, albeit unratified, record of 641.13 nautical miles in the Ocean Race. While the Swiss Bernhard Stamm and his "Armor Lux" were travelling at an average of 19.48 knots 20 years ago, the German team led by Boris Herrmann logged an average of 26.71 knots.

Vendée Globe: Is a rule change necessary?

Not only is there a radical design development in between - Imocas have also gone through several phases of development in the period under review as part of the constantly optimised class rules. These are intended to promote innovation, but also to protect the safety of the skippers after various catastrophic accidents. The same applies to financial viability.

In addition to the introduction of tilting keels, foils have been the decisive factor since the 2016 Vendée Globe. In addition to the direct financial burden, they also have an impact on the development of the entire system. Boats are designed "around the foils".

According to data analyst Douillard, however, a radical rule change is now necessary to continue the class's rapid development curve. He currently sees this at an apex and expects only small improvements without rule changes due to the natural development of the skippers and minimal adjustments to the boats. "The big increase in performance since 2002 is due to a major modification of the boats with the introduction of foils," explains Douillard. "To make a new step like this would require another new configuration, which would increase performance much further."

Elevators could take Imocas to a new level

However, this was recently averted, at least for the time being. Specifically, it concerned the legalisation of so-called elevators on the rudders. These are T-foils at the bottom of the rudders that would also lift the stern. This would allow the Imocas to actually fly, similar to the America's Cup.

However, this technical leap not only harbours enormous speed potential, but could also increase safety thanks to the more controllable flight attitude and reduce the load on the material. The current practice of "skimming" with the tail in or just above the water continues to result in crashes and nose dives, i.e. the sometimes hard diving with the nose; long and calm flight phases, on the other hand, are hardly possible. The current rules already counteract this with more volume in the bow, massive reinforcement of the hull structure and adapted foil profiles.

This is therefore unlikely to be the final solution to the problem, even if elevators would in turn increase the hazard potential in other ways due to the increased speed. It is also possible that the T-Foils would cause further as yet unknown problems. The technical and associated financial costs would also increase.

At the annual general meeting of the class a year ago, a clear vote was taken against this technological leap anyway. This means that similar Imoca designs will remain without elevators for at least another five years. However, the top teams, including Boris Herrmann, had spoken out in favour of the rule revolution at the time.

Vendée Globe: T-Foils are coming

A new build with foils currently costs five to seven million euros. Wings on the rudder blades would cause this sum to shoot up even higher, further widening the gap between the top and financially weaker teams. The clear decision is therefore not due to possible doubts about the improvement in performance. On the contrary: the company remains convinced that the development must and will come.

This was also confirmed by Imoca class president Antoine Mermod. However, the class is not yet ready for this step. And Herrmann also said afterwards: "I'm almost a little relieved that it didn't happen, but at the same time I would have liked to have seen it." Herrmann also pointed out the major technological challenge on Amwind courses.

Whether elevators would actually be miles ahead on routes around the world has yet to be proven. On a smaller scale, the technology has not yet proven to be completely superior, but has shown strong development. Frenchwoman Caroline Boule was the only one to have had major problems with a full-foiler at the Mini Transat 2023. In 2024, she set a new 24-hour record for the class in the mini classic Les Sables - Les Açores - Les Sables. With a little imagination and trust in the developments of the future, a Vendée Globe in under 70 days should be possible with the legalisation of elevators at the latest. The current record is 74 days and dates back to 2016.