Records: 222 km/h, only with wind! - Interview with professional sailor Glenn Ashby

Andreas Fritsch

· 25.02.2023

It was a test of patience to set a new record. Australian Glenn Ashby and Emirates Team New Zealand waited for months for it to finally dry out. The Australian salt lake, Lake Gairdner, was not the bone-dry salt desert they had hoped for, but was instead submerged in the rain of the wettest winter in Australia for decades. Instead of an ideal, kilometre-wide playground for the three-legged racer, which the team had built on the side during the break until the next America's Cup (AC) in order to break the land speed record of 202.9 kilometres per hour that had stood for 13 years.

In December, the time had finally come: after a long wait, "Horonuku", Maori for "gliding gently over the land", made its first tracks with a plume of salt dust instead of spray at the stern. According to the regulations, the surface must be natural and no tarmac track may be used. Salt lakes are ideal for this. And after just a few test runs, the 14 metre long and eight metre wide vehicle breaks the record: at six times the wind speed, the Australian races to the new record, which he increases by 20 to222.43 kilometres per hour increased.

Shortly afterwards, YACHT had the opportunity to speak to the new record holder Glenn Ashby, who is already back in AC preparations with the New Zealand team.

YACHT: How did you set the land speed record?

Glenn Ashby: I actually wanted to do that when I was six or seven years old. I grew up in Victoria, Australia, in the hinterland so to speak. I learnt to sail on a lake, but sometimes it dried up because it was a water reservoir for farmers. At the end of the summer it was often empty. Then my friends and I equipped the trolleys of the boats with the rigs of our dinghies and we sailed ashore. When we were about ten or eleven, we built bigger and faster trolleys. We were impressed at the time by how fast we could go! This gave rise to the dream of breaking the record one day.

You've been travelling on AC boats for many years, but also on the water with dinghies, A-Cats and other sailing companions. How does it compare to sailing "Horonuku"? Starting, for example, always looked so difficult.

The boat is really super-slow at take-off. The wing is very, very small, it is optimised to work at over 200 kilometres per hour. Up to that point it is too small, and from around 250 kilometres per hour it is too big again. The boat weighs over 2,500 kilograms, so we need around 20 knots of wind for "Horonuku" to start moving at all. It normally takes me four to five minutes to get over 100 kilometres per hour. But once we get going, it's like a train, and the wing produces more and more power, from 120, 130 kilometres per hour it's going well. Between 160 and 200 kilometres per hour, the vehicle really comes to life. From 200 kilometres per hour, you can hardly trim the foil any more, so I do it by steering.

In the video you can see how you operate the shift paddles on the steering wheel while driving, just like in a sports car. How exactly does that work?

There are still the foot pedals. The one on the left is a brake pedal, which I only need to stop. The right pedal is the accelerator pedal, so to speak. I use it to operate the hydraulic pump that moves the angle of attack of the wing profile. I can release the pressure again using the two paddles on the steering wheel. It's like the landing flaps on an aeroplane: to accelerate, the wing mast needs more profile, and the faster I go, the flatter I set them so that the resistance is less.

What course are you taking?

First, actually 90 degrees to the wind, i.e. half-wind. That's the starting position. And when we get faster, I slowly turn away from the wind to build up speed. If there's not much more going on, I drop way downwind. At this moment, which lasts about 30 seconds, the speed is at its highest.

How much space do you need for such a record run?

That's quite a lot, we need about seven to eight kilometres of space. I drive to one end of the runway, jibe at around 115 kilometres of speed, and that gives me around two kilometres of space to build up speed. We then cover 65 metres per second, so the runway quickly becomes short!

In "Horonuku" you lie in the cockpit like a Formula 1 driver, can you see much at all at that speed?

I can only see a small strip of the horizon. You can see the flags, cars.

And how does that feel?

The wind and rolling noises get stronger and stronger, and at almost 200 kilometres per hour it gets pretty loud, and the vibrations and bumps from the track are intense. You have to work really hard with the steering and paddles to stay on course. Fortunately, there are no trees or obstacles.

How dangerous was the attempt to set a record? The record holder on the water took off once at 50 knots and rolled over...

I actually felt very safe. The cockpit is designed to Formula 1 standards, a very stable carbon capsule in which I am secured with straps. I think "Horonuku" is much safer than all the sailing boats I've sailed on in my life. AC75, SailGP, Motte, all much more dangerous!

Drift is a big issue in the record attempts on the water, on land too?

Sailing boats are much lighter than our vehicle, which weighs almost 2.8 tonnes. But that doesn't matter so much on land because of the low rolling friction. But in the gusts, we also sail a good 50 to 100 metres to leeward! You can't even see that in the videos! We have a slip angle of eight to ten degrees. That's why I have to correct so much with the steering wheel. The load on the structure to the side is also much higher than that forwards. The wing takes about 1.5 tonnes of side load and only 250 kilograms of propulsion.

The wing still has an arrow-like structure, what is it for?

This is the counterweight. It balances the wing, especially when it is deformed to leeward by the gusts. There is some lead in the tip at the front to stabilise the profile.

You actually only needed one real attempt to break the record; the previous record holder took almost ten years. Were there hardly any setbacks for you? How do you explain that?

Of course, we had a great team behind us in Emirates Team New Zealand. The designers and engineers are really clever guys. We've already broken a few things during the test drives, so we've learnt a lot. But structurally we are in a pretty good position. The previous record holder Richard Jenkins has achieved an enormous amount on his own over the years. But he also had a different approach, his "Greenbird" was much lighter. He also had a lot of fast attempts, but was always only just under it. I was very lucky that ETNZ was interested in the project. The guys really had fun - it was something new!

You had the feeling that that wasn't all ...

I want to try another run and we're kind of on standby at the moment. We need a really windy day, the time window is roughly until the end of February.

How much wind do you need for the record attempt?

During the record we had very gusty conditions, it was blowing from 14 to 27 knots, the direction was turning strongly. That was very difficult, the average was 22 knots. I think if I had 27 knots relatively consistently, that would be fantastic, then we could be a bit faster. But the surface of the lake, the salt, has to be perfect for that. A lot of things have to be right.

If everything fits, what else do you think is possible?

I think 250 kilometres per hour would be feasible, after that the wing is simply too big.

During the sailing record on the water, Paul Larsen said that they found it difficult to overcome a kind of invisible limit in the water, because at around 60 knots the ventilation and cavitation at the rudder and centreboard increases dramatically. Are there such limits on land?

Not as extreme as in the water, but aerodynamically yes. At some point, wind resistance becomes a problem at higher speeds. If the wing becomes even smaller so that it has less drag, it still has to propel the vehicle without external assistance, which is what the rules for the record require. (Onemust not tow, the ed.)

Can you actually learn anything from the project for the America's Cup, or was it the other way round?

Yes, we can, because we all had to leave our comfort zone of what we knew, new tools had to be used for the computer calculations and new ideas had to be developed. One of the big plus points of the project was that we talked to a lot of experts that we didn't even know before. They have knowledge in areas in which we are not so familiar. We got to know good engineers and new machines that can help us to make parts and calculations for the America's Cup. The spin-offs are bigger than we thought!

The record-breaking journey in 360-degree video

Why can you sail faster than the wind?

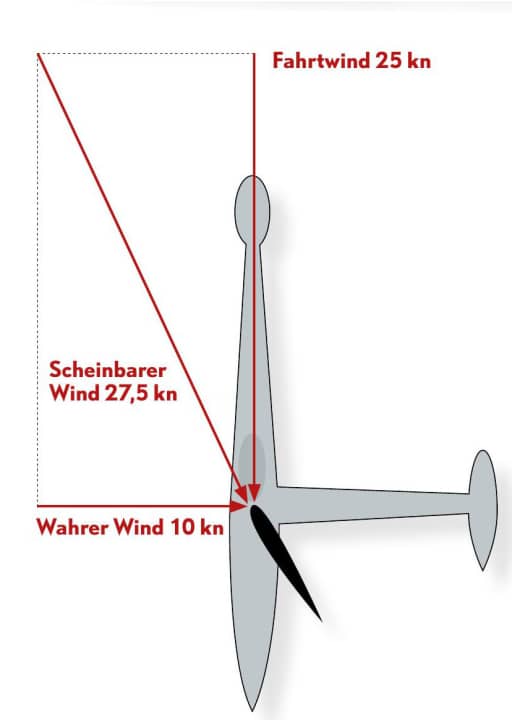

Many sailors may wonder how a boat can actually manage to sail at several times the wind speed. The answer lies in the interplay between the true wind, the airstream and the resulting apparent wind, as well as the profile of the sail. Due to the different lengths along the sail profile, the wind is accelerated to more than the true wind speed on one side.

This creates negative pressure, which pulls the rig and boat in this direction (Venturi effect). If the craft offers very little frictional resistance in the water or on land, it accelerates to slightly above wind speed. The airstream is added and the resultant of the airstream and the true wind is slightly stronger than the latter. The vehicle continues to accelerate, the airstream increases and so does the apparent wind.

From this effect onwards, the sail creates its own wind, so to speak, because the resultant force continues to rise due to the increasing airstream. This continues until the resistance in the water or the wheels on land and the wind resistance of the vehicle are greater than the force that is pulling. America's Cupper can thus reach two or three times the wind speed, land vehicles or ice sailors even five to six times.

Also interesting:

Andreas Fritsch

Editor Travel