For more than three weeks now, I've been invited to farewell dinners at lunchtime and in the evening. It's about time this came to an end, I'm starting to get a belly. On the other hand, I can eat a few reserves and don't have too much time to think about the very long distance ahead of me.

On the morning of my departure, several friends stand on the quay to wish me a good journey and bring me cakes, sweets or tins of sardines. I am very touched. The "Baluchon" is already fully loaded, but I don't dare refuse.

The exit from the harbour and the bay is leisurely with a light wind. I am accompanied by several boats and, for a while, even by the coastguard speedboat. At first I'm worried and hope that the police don't want to ask me for my boat papers and check my equipment. But even they only make this small diversions to wish me a fair wind.

After leaving the fairway, I am finally alone again. As I open the map on my tablet, I'm overcome by a feeling of dizziness. The route suddenly seems disproportionately long. I wonder if I've lost my common sense. Why else would I want to travel such a distance in such a small boat?

Pain and broken batteries make life difficult for Quenet

To make matters worse, I feel a sharp pain in my chest. In a moment of hypochondriacal madness, I imagine that poor me is having a heart attack. I realise that my stay in New Caledonia was more than warm and that the idea of travelling alone again can be frightening. But kicking the bucket is a bit of an exaggeration, especially as I still have a lot to do.

The electric autopilot does its job very conscientiously, but every now and then it goes into standby mode. I know this problem, it is due to a not quite clean electrical connection. I check the entire cable, spray it with contact spray and scratch the connections a little, but the problem occurs more and more often. Strange!

I then check the batteries, and lo and behold, what a shock! One has just eleven volts and the other 11.5 volts - that's not exactly top form. So the batteries shouldn't be that flat. When I try to charge them individually, I realise that the eleven-volt battery is no longer charging. After a whole day of charging, the other one manages to reach twelve volts, only to slowly drain again over the course of the night, even though no device is connected. In short, they are broken.

It's just under 6,800 nautical miles to the next battery shop. For a moment, I consider turning back and travelling to Koumac, a small town in the north of New Caledonia, which I could reach in 24 hours of sailing. But the very thought of going back is deeply repugnant to me. No! That's out of the question. I'm heading west, whatever the cost!

A self-built wind steering system called Bébert

I just have to think of something so that the "Baluchon" can steer itself. I spend almost a whole day thinking about how I can use the few materials I have on board to build a kind of large wind vane that will act on the rudder if the boat veers off course. I build a windvane control from an old sheet of plywood that I found in a rubbish bin on Guadeloupe and kept under my mattress in case of a leak, a piece of PVC pipe that I could use to connect my two spars to form a makeshift mast if the worst came to the worst, my boat hook, which I saw through, and a large plastic spool for winding fishing line.

Oh wonder! After the second attempt, the wind vane works perfectly. I am so impressed that I watch for almost an hour like a hypnotised fool as this improvised installation steers my boat perfectly. Of course, it requires a bit of sensitivity when tensioning the lines and the sail has to be trimmed to the millimetre. But the whole thing works silently and with great efficiency. It's almost magical! I decide to christen the wind vane "Bébert" (a reference to my friend Bébert from Brittany, who talks incessantly and is completely inefficient).

Satisfied, I continue on my way and let the AIS be powered by the least weak battery. I have a battery-powered emergency navigation light in case I cross another boat. I charge my tablet and e-reader directly at the output of one of the solar panels. This takes much longer than using the battery, but it works perfectly. It would have been really annoying if I had turned round because of this trifle.

Two not very bright seagulls for company

When I reach the entrance to the Torres Strait between Papua New Guinea and northern Australia around 20 days later, the grey, gloomy weather is over. The sky turns blue and the sea turquoise. I take the opportunity to dry my mattress and the inside of the boat. The sea has been pretty vicious and sneaky for a good week. It gave me plenty of saltwater showers, especially when I had to stick my head out of the hatch to adjust Bébert, which made me swear profusely.

The cabin of the "Baluchon" is wet, sticky and salty. It stinks of mould, sweat and rotten fish, and I no longer have any dry clothes. Two seabirds, a kind of seagull and a somewhat smaller brown specimen, accompany us for two days. They sit on either side of the boat on the ends of the spar trees. It's a funny sight to see them flapping their wings with every roll and trying to keep their balance.

When I consider that the two birds can't be very bright, because why else would they put themselves in such uncomfortable positions when there are stable little islands all around, I realise that I am the last person on earth who is allowed to make such a judgement.

The strait, with its dangerous reefs and treacherous currents, is very forgiving towards me; there is a moderate wind. I have timed my departure from New Caledonia so that I arrive here under a full moon. That way I can easily recognise the reefs and small islands at night.

Even the Australian Coast Guard is impressed

What I am most afraid of since Nouméa is the reaction of the coastguard in the Australian zone. I've heard so many stories about this famous authority! For someone like me, it's a bit unsettling to have to deal with such strict people.

When I see my first control plane, I have already been cruising through countless coral reefs for 24 hours. My handheld radio is ready, as is a piece of paper on which I've written down everything the officials might be interested in: my date of birth, my shoe size, my grandmother's maiden name and the colour of my pants.

While I wait tensely, I clear my throat thoroughly. When the radio call comes through, the very polite officer on the other end just wants to know where I'm from and where I'm travelling to in my little craft. He also asks me about the size of my boat, and when I answer him, I hear shouts of "Wow!" and laughter from the aircraft cabin. The man then wishes me a safe journey on my "incredible adventure". When the conversation is over and the aeroplane has left, I feel quite nauseous and very moved.

Quenet urgently needs to rest

Despite my lack of sleep and tiredness, I gradually pass through the Torres Labyrinth without any major problems until I finally pass close to Hammond Island, which is right next to Prince of Wales Island in the very north of Australia. It's not really necessary for me to get so close to the coast, but I want to get within range of the Australian mobile phone network so I can send a few messages. Bingo! It works. I receive a text message: my phone provider welcomes me to Australia.

I cross three large freighters travelling in single file behind each other. Our course lines overlap a little, but I have enough wind to manoeuvre and avoid them. The freighters, however, seem a little nervous. Two of them are blaring their horns like crazy.

My condition indicates that I'm really exhausted. I urgently need to rest and regain my strength over the next few days, especially as I've only completed just under a quarter of the route. I manage to post something on my Facebook page and send a few personal messages. Then I quickly check my emails: nothing important, so I switch the phone off again and head back west.

Rubbish and weak winds wear down the mood

A few hours later, the strait is finally behind me. I prepare myself a large portion of freeze-dried pasta and then lie down to take a nice nap. I set the alarm to go off 40 minutes later, but forgot to activate it. When I wake up almost four hours later, it's broad daylight and I'm in a zone teeming with freighters.

The subsequent crossing of the Arafura and Timor Seas, where I always sail along the North Australian coast, is as boring as it is depressing. Boring, because the weak wind always comes from astern and forces me to sail in a zigzag course at the speed of a sea snail. Depressing because the sea is practically covered in a carpet of plastic rubbish. It's the first time I've seen so much plastic waste since I left. Man really is a cursed polluter!

After about 20 days, I finally reach the Indian Ocean. The slow pace almost drives me mad. Barely 100 nautical miles past the westernmost point of Australia, the wind finally turns to the south-east. But it's not a girlish trade wind like in the Pacific.

100 nautical miles a day in rough seas

The wind will remain at 30 or 35 knots for most of the rest of the way, which is quite a lot for a four-metre boat. But I can feel that my little "Baluchon" is in her element and is happy to fight the sea and the wind. My daily average is rarely less than 100 nautical miles, even though the sea is pretty choppy. Sometimes, when the wind dies down and the swell is a little less, I manage up to 120 nautical miles a day - a nice change from my miserable Australian average.

To get an idea of the conditions under which I am travelling, you only have to imagine shooting down an almost 6,000 kilometre-long black ski slope in a bobsleigh, which has previously been under constant fire from the artillery of a highly motivated Teutonic army.

The tiny piece of sail starts to shake like a Breton alcoholic with Parkinson's disease

Several times a day, the "Baluchon" is sent straight to the mat by the heaviest of blows. Then there is a brief moment of silence before she straightens up again and braves the wind. The tiny piece of sail starts to shake like a Breton alcoholic with Parkinson's, causing crazy vibrations throughout the boat. Then Bébert slowly brings the "Baluchon" back on course and she tackles the next waves.

Eat, sleep and read in the tiny cabin

I manage to develop a kind of sixth sense: When I sense that we're about to get hit again and lie on our side, I brace my feet against the ceiling so that I don't get thrown out of my bunk. All the objects that aren't strapped down are also catapulted through the area during the impacts. My Swiss Army knife, my head torch and my reading glasses fly through the "vastness" of the cabin more than once. Each time it takes me an eternity to find them again in the boat, which is rolling like crazy.

Wedged into my bunk as best I can, I try to continue living a "normal" life as best I can. I spend my time daydreaming, reading, eating cold food and sleeping. When I have enough power for my tablet, I listen to "La Grange", my favourite ZZ Top song, on an endless loop. I think this good old rock fits perfectly with the conditions and rhythm of this trip.

I also reread "The Old Man and the Sea" and ask myself the same question I did when I first read it at the age of eleven: Why didn't the old man, when he still had his knife, cut more pieces out of the swordfish before the sharks could snatch it all away from him?

I also take on Baudelaire again, but this time I try to read it out loud. I stand upright in the hatch and occasionally get a load of water in my face. So I recite the verses to the ocean, for a few flying fish and seabirds that don't seem the least bit interested.

La Réunion is reached after 77 days

When the island of La Réunion comes into view after 77 days at sea, I am very happy. I really pushed myself beyond my limits during this very long stage and learnt a lot about myself and the sea. Apart from the battery episode, I didn't really have any technical problems. I was well supplied with food and drink as, in addition to the 110 litres of water I had on board at the start, I collected around 30 litres of rainwater and treated around ten litres of seawater with the manual desalinator.

As I drive the last few nautical miles along the coast, my mobile phone picks up the French network for the first time in 20 months. I receive a text message: "Currently: 25 per cent discount on brake pads at your dealer." Battery 1 is dead for good, and battery 2 shows between seven and eight volts.

I move the boat into the harbour with the wriggriemen. There are all sorts of people on the quay who have come to greet me. It's the first time this has happened to me since I started my journey. Someone is even waving a Breton flag. But as I step onto the jetty, my legs barely obey me. I find it incredibly difficult to walk straight ahead. I'm a bit embarrassed. Everyone must think I'm totally drunk and have overdone it with the bottle of rum I was given on departure. That must reflect rather badly on Brittany!

As soon as the harbour and customs formalities are completed, people queue up at the jetty to talk to me or bring me something to drink or eat. After such a long time alone at sea, it feels strange.

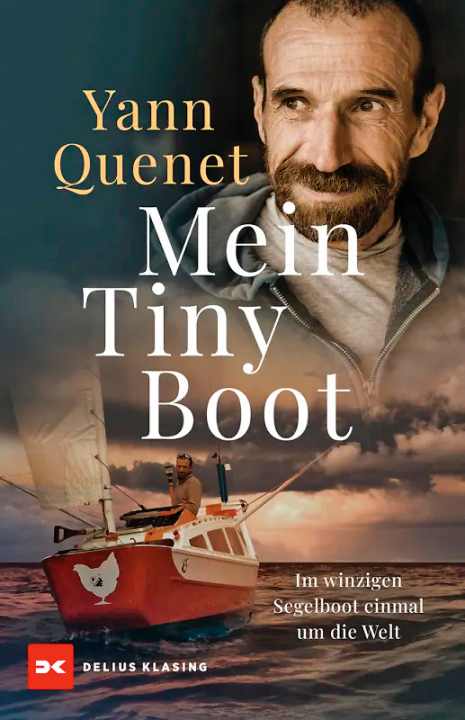

The book about sailing around the world

French single-handed sailor Yann Quenet reports on his extraordinary adventure with the minimalist four-metre sailing boat "Baluchon" in the recently published book "My Tiny Boat" on 215 pages with numerous photos and illustrations.