Weather knowledge: Strong gusts out of the blue - development and sail handling

Dr. Michael Sachweh

· 11.04.2023

A gusty wind is not exactly what sailors love. In contrast to a thunderstorm, a gust only announces itself at short notice, if at all, and often arrives suddenly. If you're lucky, you'll notice the threat immediately beforehand, albeit indirectly: the surface of the water to windward darkens, whitecaps form and - when the going gets tough - spray flies through the air.

Gusts are not an exceptional phenomenon. They are as much a part of the sailing weather as the waves are of the sailing area. In certain weather conditions, near the coast and on inland waterways, they are an almost everyday experience. For those who are familiar with them, they not only quickly lose their terror. They can even be useful, for example during a regatta.

More articles on the subject of gusts:

A little gust theory

A gust is when the average wind speed is briefly and significantly exceeded. According to the definition of the German Weather Service, it must last at least three seconds and be at least ten knots above the previously prevailing mean wind.

In moderate wind speeds and under land cover, sailors usually experience gusts as short gusts of wind. In a storm out at sea, however, a gust can last half a minute or longer - impressively accompanied by the slow rise and fall of the whistling and howling in the rig.

A gusty wind is not only capricious in terms of its strength, but also in terms of its direction. It usually turns by 10 to 20 degrees in a gust, sometimes even by up to 40 degrees. In the worst-case scenario, an unprepared skipper may lose control of the boat for a short time, either because the sails suddenly flip when the boat is sailing high upwind or because the boat is pushed onto its side with force. Both phenomena, speed and directional gusts, therefore pose a threat.

In meteorological terms, the gust is an expression of turbulent air movement. A distinction is made between dynamic and thermal turbulence.

Dynamic turbulence

Sailors are familiar with dynamic air turbulence, whether on lakes, rivers and canals inland or with offshore air currents on the coast.

The contact of the flowing air with the differently structured land surface results in speed differences in the flow field. As soon as the wind hits the ground, it weakens and turbulence occurs - a kind of stop-and-go in the airflow, combined with rapid directional fluctuations. In addition, the greater proportion of friction in the airflow ensures that the land-influenced wind is more favourable.

The closer you sail to the coast and the more frictional resistance the current experiences from hills, mountains, buildings, cliffs and other obstacles, the more gusty the offshore wind will be. Furthermore, the stronger the general air current, the stronger and more unpredictable the gusts.

The shaded area of a cliff is therefore not always a safe haven. Although you are protected from strong winds, they are extremely unstable in terms of direction and strength and therefore unpredictable. The extent of such a shaded area can vary greatly. If, for example, tree-lined avenues or houses standing together line the shoreline, a minimum distance of up to 30 times the height of the trees or buildings is required to escape the unpredictable gusts.

Another reason for dynamic turbulence is air currents of different speeds in the upper atmosphere. In unstable weather conditions, these gusts can propagate downwards to the water surface.

Thermal turbulence

Another cause is thermals. If the temperature difference between the lower and higher atmosphere exceeds a certain level, the air stratification becomes unstable: the warmer air swirls upwards in upwind vents, while cooler high-altitude air sinks downwards. This up and down in the air flow results in gusty winds.

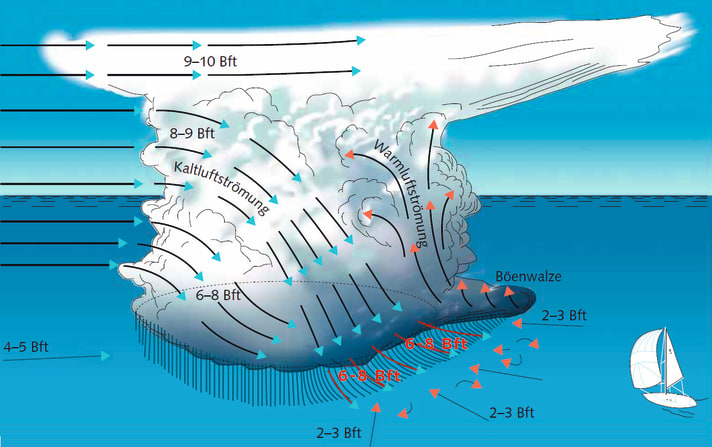

A glance up at the sky reveals the danger: cumulus clouds piled up more or less high, up to shower and thunderstorm clouds (cumulonimbus). If an only moderate air flow at the bottom is overlaid by a very strong high-altitude wind - watch the speed at which the tops of the cumulus clouds move! -The gusts are particularly violent. And also important to know: The wind always turns to the right in the gusts.

The more unstable the air stratification and the higher the clouds are piled up, the stronger this wind shift. In individual shower and thunderstorm clouds, it can turn right by 30 to 40 degrees. After the gust, it turns back again. However, if the shower clouds form a long line, as is typical for cold fronts, the wind shift can be even greater. In this case, however, the wind does not turn back afterwards, but maintains the new direction.

Gusty weather conditions

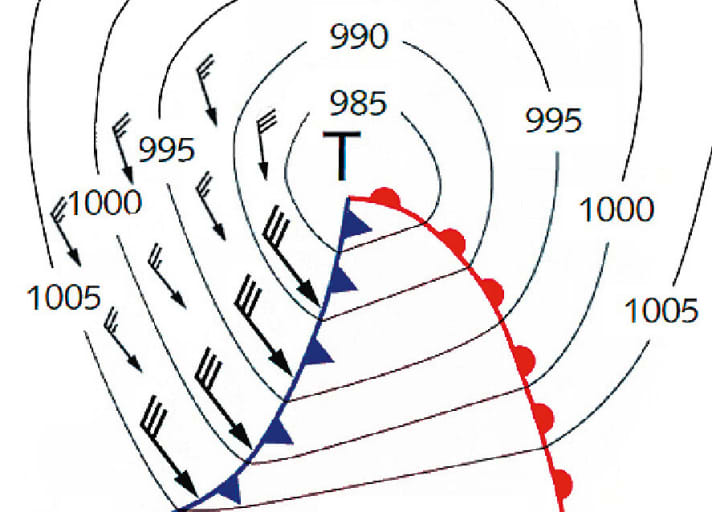

Low pressure areas

In our climate zone, passing low-pressure areas are part of everyday sailing. Warm fronts and warm sectors are followed by cold fronts. This poses the greatest threat to a normal low: The stable air stratification abruptly becomes unstable.

In summer, the front often forms a long line of heavy showers and thunderstorms. The wind change can be considerable. What was previously 2 to 3 Beaufort from the south-east to south-west becomes gusts from the west to north-west with 6 to 8 Beaufort or more with the passage of the front. The wind will then shift back a little and blow relatively evenly. This will be followed later by back-to-back weather with a mix of sun, clouds and showers. There will be gusts again, but they will not be as strong and directional as directly on the cold front.

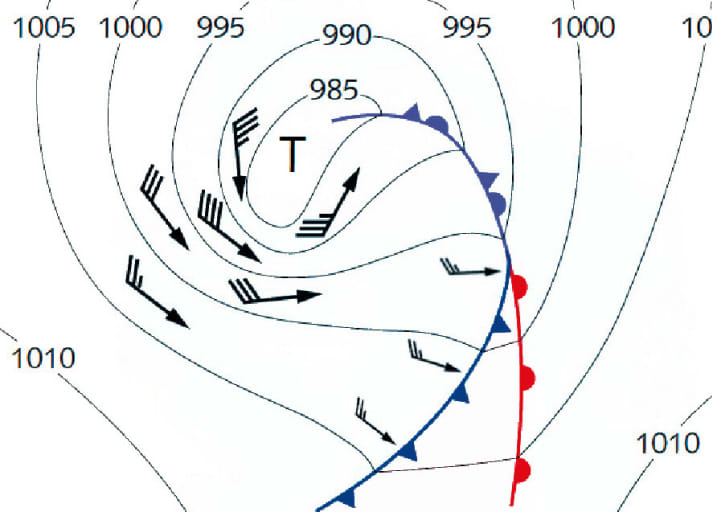

Trough low

A special form is the trough low: as a result of a renewed drop in pressure in the centre, a bulge sometimes forms in the core of ageing lows. A strong wind or even storm field forms on the southern and western edge of this trough. This is an insidious low-pressure variant, because after a fairly mild passage of the cold front squall line and only a few backside showers, sailors think they are already on their way to the next high.

Signs of a trough are the aforementioned rapid drop in pressure and lines of heavy showers and thunderstorms. The gusts are often as violent as those on a strong cold front. Nasty wind shifts are also to be expected.

Heavy early and late season

Regardless of such low-pressure escapades, the wind is gustier towards the end of the sailing season than at the beginning, assuming the same weather conditions. This is due to the water temperature, which has a significant influence on the temperatures in the lower atmosphere. The combination of a still relatively warm water surface with the gradually cooling higher atmosphere from the end of August leads to an increasing frequency of weather situations with unstable air stratification. This in turn promotes atmospheric turbulence. And not only in the North Sea and Baltic Sea, but also in the Mediterranean - even if the south often continues to spoil you with sunshine and warmth until the late season. Mediterranean autumn thunderstorms indicate how violent the gusts can be as soon as the air stratification becomes unstable.

Coasts with gust potential

Due to the increased dynamic turbulence caused by the bottom topography, offshore winds are always gustier than onshore winds. If the coast is then divided into mountains, hills, capes and cliffs, sailors must be prepared for exceptionally gusty winds. A skipper entering a harbour can then expect a challenging approach manoeuvre, while the departing sailor looks for free sea space as soon as possible.

A particularly unpleasant situation arises when there is a combination of high dynamic and thermal turbulence. One example is the strongly indented east coast of Schleswig-Holstein with a predominantly favourable but windy westerly weather situation in summer. In the lee of such coasts, the dynamic land turbulence virtually piggybacks on the thermal land turbulence - sailing becomes a gusting gauntlet.

Such gusts are only topped by heavy downdraughts. A notorious example is the Croatian coast in pronounced Bora weather conditions. There is almost no warning at all for sailors, as the wind literally falls unhindered from diagonally above into the coastal area. It is even accelerated by the ramps formed by the bare mountain slopes and the vegetation-poor, whaleback-shaped islets of the Kornati islands.

There too, thermal and dynamic turbulence form an unholy alliance close to land, as the bora is almost always accompanied by sunny weather. Fortunately, strong downslope bora winds tend to occur in the winter months and only bother sailors in the early and late season.

How far off the coast do gusts occur?

Distances as a function of obstacle heights

- Steep coast, cliffs: 7 to 10 times their height

- Dyke, dunes: 10 to 15 times their height

- Trees, houses: 15 to 25 times their height

- Avenues, closed development: 25 to 30 times their height

Recognising, parrying and using gusts

Gusts are a dangerous element at sea, and there is little warning time. Skippers should therefore always check early on whether they could find themselves in a dangerous situation. Scattered clouds in the sky are an indication, as are showers or thunderstorms within sight. It also becomes critical if a cold front is approaching or a course close to land is planned.

Immediate warning signs of gusts to windward are the rippling of the water surface, which leads to a characteristic darkening of the gust area, as well as an accumulation of white whitecaps and also yachts and dinghies with conspicuous heeling. The skipper then has a few minutes until the gusts reach his own boat.

During this time, he must check whether reefing is necessary and from which direction the gusts are coming. If the ship is sailing high upwind on the starboard bow, the right-hand gust can cause the sails to shift and the ship to heel violently in an unexpected direction. On the other hand, on the way into the shadow of land, the wind shifts back a little, where a high downwind course on the port bow can prove fatal.

If a line of showers or thunderstorms is approaching, you should scan the sky for a dark, elongated cloud roll. This usually marks the front of the gust front. Beware, the most violent gusts occur immediately at the beginning of the strong wind phase and they almost always come from the west to north-west - regardless of which direction the wind was blowing from before!