Turning and turning aside: Seamanship that creates calm - an ingenious manoeuvre

Lars Bolle

· 23.02.2023

The aim of this manoeuvre is to trim the yacht to the wind and waves so that it moves as little as possible. The aim is to balance the yacht so that nobody has to row. This creates an incredible sense of calm, regardless of what is happening around you.

Turning, which refers to the initial manoeuvre, and the subsequent leaning, the state of equilibrium, are recommended for various purposes. It appears again and again in the literature as a tactic for weathering a storm. But opinions differ on this.

Circumnavigator Susanne Huber-Curphey describes in her book " Single-handed for two "We are not convinced of the tactic of tacking in a storm, because at a certain point of wind and extreme wave the yacht will still be overrun ... In addition, sometimes there is hardly any wind in the deep wave troughs, while a few seconds later the yacht can be pushed almost flat on the water by the full force of the wind at the top of the wave."

For cruising yachtsmen, the enclosed is very suitable

However, the vast majority of sailors never experience such conditions. However, those who are mainly travelling close to the coast often do not have enough sea space to weather a storm.

Nevertheless, even for the average sailor there are many conceivable situations in which lying alongside is a good idea - whether in a medical emergency or as a first response to a man-overboard manoeuvre to repair something, reef, cook something or go to the toilet in a safe way. Skippers should think about this point in particular. It is well known that going overboard is often a consequence of ditching over the railing.

The body has to relax, which can lead to uncontrolled movements. To make matters worse, the person urinating can only hold on with one hand and is usually on the leeward side of the swaying boat.

It can also lead to so-called micturition syncope may occur. This is a brief loss of consciousness caused by a sudden drop in blood pressure as a result of the body changing position and the pressure on the bladder decreasing. If this fainting occurs at the edge of the boat, it is very likely that you will fall overboard.

Business below deck is much safer. What's more, it can be done with more dignity on a calm yacht than target practice in a bucking and swaying cabin.

It may also be helpful in the fight against seasickness. If parts of the crew are cancelled, the skipper may be left to his or her own devices. Giving the crew or - in the case of couples - the partner a quarter of an hour or even 20 minutes to collect themselves or to give them courage can prevent a total breakdown.

Enclosed with modern yachts

But is every yacht suitable for levelling? In forums and literature, it is repeatedly stated that only long keels are suitable because they are easy to lean out due to their long, large, evenly distributed lateral plan. Modern cruising yachts with a flat U-frame and short keel, on the other hand, are not easy to lean because they keep picking up speed via the drifting foredeck.

We tried it out. We set sail in 7, in gusts of 8 Beaufort with a Beneteau Oceanis 34.2 from the Heiligenhafen charter centre. With waves up to an estimated two metres in height, we tried out the different ways of staying afloat. For example, with differently reefed sails or in front of the top and rigging.

We trialled alternatives, such as counter-bolting under engine power, under sail high on the wind or using a sea anchor. The results were very different, but they confirmed one thing:

Even with a short keel, levelling is no problem and the classic method - with a backed headsail and balanced mainsail - is the best.

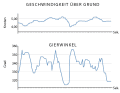

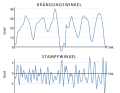

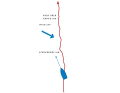

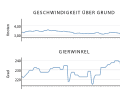

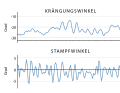

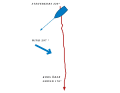

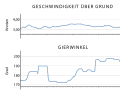

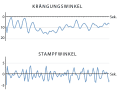

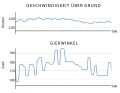

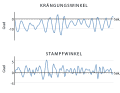

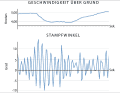

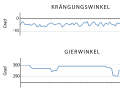

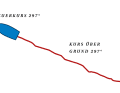

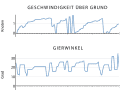

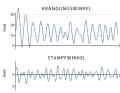

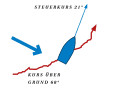

In order to objectify the impressions, we recorded the yacht's movements in each case. The graphs in the following overviews show the yacht's course over ground as determined by GPS and the distance travelled in two minutes, i.e. the drift direction and speed. The orientation of the ship symbol indicates the average heading, i.e. how the yacht was usually orientated to the wind and waves. The change in speed and heel, yaw angle and pitching angle over a period of one minute are also shown. These were determined using a smartphone with an integrated compass and gyroscope. The rule of thumb applies when reading the curves:

The flatter and more elongated, the smoother the movement.

However, the results only allow one statement to be made for this particular yacht. As different as the boat types are, there are just as many different settings. Each skipper must find the most suitable one for themselves. In most cases, however, the enclosed should work.

Under sail against

Although the yacht sails fast at almost five knots and also about 42 degrees to the true wind, it makes little way to windward due to drift, current in Fehmarnsund and strong wave shift. The tacking angle is about 60 degrees. She overtakes strongly about every ten seconds, constantly up to 30 degrees and is taken off course by windward yaw and waves hitting the hull. This resembles a snaking line with deviations of up to 20 degrees to either side of the course. The hull pitches with strong jerky movements. All in all, a very uncomfortable ride.

Tacking with 1st reef in genoa and main

The genoa and mainsail are furled slightly, the genoa so far that it fills the foresail triangle. Overlapping genoas are thus also released from the spreaders. Due to its still relatively large surface area, the mainsail acts like a wind vane, the yacht keeps turning into the wind direction and takes the waves diagonally from the front. This explains the still noticeable pitching and also the yawing by about 20 degrees. The mainsail always kills something, which means wear and tear. At almost three and a half knots, the yacht still has plenty of speed ahead and drifts only slightly to leeward.

Tacking with 1st reef in genoa and 2nd reef in main

The genoa is unchanged from the previous situation, but the mainsail is furled so much that only a small triangle remains. The furling itself, as well as the reefing, is much easier than standing upwind. This sail position ensures the most pleasant behaviour of all. The yacht only heels at around ten degrees and hardly rolls at all thanks to the support function of the mainsail. This can be taken so close that it does not kill, i.e. it is at right angles to the wind. The drift angle is slightly less favourable than before, the speed is about the same.

Tacking without mainsail

Although the drift speed is reduced due to the further reduction in sail area, the course over the ground is directly to leeward. At first, the impression is of great calm, as the yacht hardly heels at all. But this is deceptive. The rolling movements are much more unsteady and with greater amplitude without the support function of the mainsail. The heading also varies greatly. Only under genoa does the yacht constantly try to drop, especially when the bow is caught by a wave. She lies somewhat with her stern to the wind, which increases the risk of foundering.

Under machine against

As the photo shows, counter-attacking is not a real alternative for calming the ship, for example when cruising seems too uncomfortable. A strong engine is a prerequisite anyway, which is often not available on older yachts - sometimes you can barely manage to counter the drift. But this course should also be carefully considered from a comfort point of view. Heeling and yaw angle are negligible, but there are violent pitching movements about every three seconds. The flat foredeck of the U-shaped bulkhead causes a lot of crashing. A jerky, annoying and tiring movement.

Running off the top and rigging

The wind here comes from port, the rudder is amidships. The hull aligns itself almost exactly at right angles to the wind and waves and barely makes any headway - the ship drifts diagonally away from the wind. However, it is not possible to create calm in this way. Although the pitching is negligible, the yacht overturns by around 20 degrees with every wave. It also lurches with a yaw angle of around 20 degrees. Both movements together are perfect for causing seasickness. The rolling also makes working on deck very dangerous.

The sea anchor as an alternative?

A sea anchor with a diameter of 80 centimetres on a 30-metre line had no noticeable effect. Regardless of whether it was attached to the bow or stern, the yacht always lay crosswise to the wind and even travelled over the ground in the same way as without the anchor. In addition, it can only be retrieved with a great deal of force - so it is not recommended for short-term mooring.