A moment's inattention, the wave not steered out, and the bow crashes into the sea, sending the spray flying and the boat literally into the brake blocks. Outraged and angry, the leech of the headsail rattles briefly in the 25-knot gust because there is too much height. You can feel the finely atomised, salty spray on your skin as it briefly passes over the helmsman.

In many parts of the world, this would be the moment to pull the oilskins further closed, duck behind the cabin superstructure and fervently curse the plan to sail 20 miles to the next island.

From Kos to Kalymnos

But not here in the Greek Aegean off Kalymnos at the end of June. Shorts and T-shirts are enough at 35 degrees, with a stiff breeze and light spray providing welcome cooling. Nobody in the crew of four thinks of folding up the huge sprayhood of the brand new Beneteau 46.1. After arriving, the boat lies levelled out on the deep blue sea. And on their faces at the cross there is a blissful grin instead of grim determination.

We knew it was coming! The northern Dodecanese from Kos in the Meltemi season - that means sailing against the wind for a few days after the start and heading north. The advantage compared to the Cyclades: The direct distances are shorter, usually around 15 to 17 miles, so it's not too much of an imposition even at the cross. On the opposite course, you can then fly southwards as close as possible. And if you want, you can discover a different island every day, which always tells its own story.

Yesterday we were on Kalymnos, the island of the sponge divers. For centuries, people there risked their lives in search of the gold of the deep. The tradition is still alive everywhere: A museum tells the story and every family knows anecdotes from back then.

From Kalymnos to Leros

But today we're heading north to Leros, the island of the captains - and, to a lesser extent, the Italian fascists. If you want to experience the one story, sail up the east side of the coast to Agia Marina or Panteli; for the other history, choose the west side to Lakki. We want to visit the captains and "Harris Bar", the most spectacular place for a sundowner.

After the long cross, we are surprised by a Greek in the boat off Panteli; he helps us tie up to the new mooring buoys. He quickly threads our line through the eye and then collects the mooring fee. There's hardly anything like this anywhere else in Hellas. But it's all the more welcome here, because the rocks in front of the village often require shore lines that are difficult to tie up anywhere.

Safely moored in front of the picturesque village with its whitewashed houses and six windmills on the hillside. There, in the first mill, you will find "Harris Bar". If you're fit, you can puff up the steep hairpin bends yourself. We take a taxi after a sporty day of sailing. And we are amazed! We are captivated by the sensational view of the harbour bay and across the island to the next bay. You simply can't get enough of so much picturesque beauty. The one sundowner quickly turns into two. Or three. Or so ...

The next day, we get to the bottom of the matter with the captains. We meet the warden in the museum of the old military fortress at the top of the hill. He tells us why there are so many beautiful stately houses in Agia Marina, shining in pastel colours, richly decorated, quite different from the plain white houses of Panteli.

"The Dodecanese was repeatedly overrun by the Ottomans. The inhabitants of the large islands of Rhodes and Kos fought back with all their might. As a result, the towns were often severely destroyed and the inhabitants enslaved. What remained were occupiers." Leros, however, was too small for this, quickly surrendered and agreed to pay taxes to the Turks in return for its independence. The economy here flourished for a long time, the captains went on trading voyages and the wealth grew. Panteli, on the other hand, remained a place of fishermen. "They lived simpler lives!"

It is stories like these that make each island of the Dodecanese so unique. Although, of course, the twelve main islands between Patmos in the north and Rhodes in the south also have things in common. Almost all of them have indented coasts, offer plenty of great little island harbours and a rich selection of well-protected anchor bays; crystal-clear water and good sailing winds to boot.

From Leros to Lipsi

It will take us to the next island the following day: Lipsi. Another cruise, but this time more relaxed, after three days of 17 to 25 knots, the Meltemi only puffs slightly.

Lipsi has everything sailors could wish for: beautiful anchorages, tavernas on the beach and a pretty little main town with a harbour in the middle. Our "Salty Lipps" glides along gently undulating hills, some of which are surprisingly overgrown with greenery, today without any salt on its face.

Behind the greenery on land lies a small success story of the island, which is why we came here: wine growing. Manolis Vavoulas and his wife Sally, a British woman who first succumbed to the island's charm on holiday and then to that of the moustachioed Greek, are already waiting for us in the harbour, as she smiles and tells us.

"Jump in the back, we're going to the vines," Manolis tells us, and we're already sitting in the back of his pick-up and speeding along the winding island roads. Again and again, carefully tended vineyards line our route. Lipsi is famous for a red grape: Fokiano. "It's only grown on Samos and Ikaria, nowhere else in the world," says Manolis. There are over 200 of these rare grape varieties in Greece alone.

Like almost everyone here on the island, the winemaker and his family have been growing wine for their own consumption for generations. But in 2013, he, his old school friend, who works as an electrician, and Sally decided to make more of it. "There was a support programme for start-ups from the government, so we took the plunge, bought more vines, professional equipment, barrels for refining and built a neat little house for storage and wine tasting."

The couple's good fortune: A wine expert from Athens, who teaches viticulture there as a professor, had been holidaying on the island for years, became aware of them and advised them on the development of new vineyards. In recent years, they have won many awards and have spread the name of the tiny island around the world. You can tell that their success makes them happy and they both beam when they talk about it.

The wine tasting even meets with the approval of our professional sommelier sailing with us: very good quality. After an unforgettable tasting, the hosts dismiss us for dinner. Their insider tip: goat or seafood risotto, either at "Manolis Tastes" or more down-to-earth at "Kalypso". Another wonderful, unique island story.

From Lipsi to Patmos

The next one comes at the northern turning point of the trip: Patmos. With the sheets already shrouded and without a reef, we head west - fantastic sailing. The destination of our shore leave was already clear before we arrived: the monastery and the Grotto of Revelation. Almost 1,000 years old, the grey-brown fortress sits high up on the hilltop of the island, right next to an ancient grotto where the evangelist John wrote his "Revelation". The island is an important site for religious pilgrims from all over the world. We are not part of this target group, but a bit of culture is always a good idea.

The approach to the main town of Skala emphasises what a great destination the island is. As we enter the deep bay, there is a pretty anchorage next to the next on the starboard side. But we want to get to the harbour. There is meltemi on the side. And the anchorage there is hard, very hard. The iron slips twice. At the third attempt, a friendly Brit calls over to us that if there is already a lot of chain, we should stop once and drive really hard into the chain so that the anchor really digs in. No sooner said than done, and finally the iron holds.

Later, Peter tells us that he has been moored here for two days and that many yachts have had the same problem. "But most of them just let the anchor slip and hope it goes well. Maybe - or maybe not!" We say thank you with a bottle of Lipsi wine and make our way into the town. The town is bustling with activity because of the cruise ships. Bars, restaurants and souvenir shops are lined up one after the other.

Of course, we also have to visit St John's Monastery. It is indeed impressive: a narrow, intricate village nestles around the fortress. A labyrinth of narrow, whitewashed alleyways, interrupted only here and there by a bar, a shop or a bakery. And at its centre is the Orthodox monastery. The chapel, overflowing with gilded and silver-plated relics, is small, but the complex is truly a fortress of faith. Monks still live here. The view from the complex high above the harbour bay is imposing, almost majestic. You can look deep into the bays, in the background the Meltemi blows white whitecaps onto the deep blue sea. An excursion that even hardened atheists will find reverent, if they can make it this far.

Back on the boat, the question arises as to where to go for dinner. After all the sightseeing through the town, we decide on the convenient solution: the "Votris" is just a stone's throw behind the yachts moored at the town pier, above the small supermarket. We are addressed at the table in accent-free German. Sofia Vasilakis grew up in Germany and on Patmos at the same time, and the restaurant is a large family business. And it turns out to be the best address of the whole trip. The food is fantastic, the wines selected, the service unobtrusive and cordial.

We want to know from her what it's like to live here as a child of two cultures. "Why don't you come round tomorrow morning, my father will be there too, you have to hear his story," she says with a smile. And so we do. And we meet Thanasis Vasilakis, the son of a fisherman whose family emigrated to Australia in the economically difficult 1950s.

"That has been the fate of many Greeks, as it is again today. After the economic crisis in 2008, as many Greeks left the country as after the Second World War!" Thanasis himself returned at the end of the 1960s, hired on as a steward on cruise ships and fell head over heels in love with the passenger Susi.

For her sake, he leaves home and emigrates to Heidelberg, then Karlsruhe. "But my soul always stayed here on Patmos!" You never forget the sea when you are born on an island, confirms his daughter. In summer, the then young family regularly travelled home. For over 13 years, they renovated the old house. And whenever they return to Germany, Thanasis falls into melancholy. Until he and the whole family decided to stay on Patmos permanently. Since he has been living here again, in his homeland, and working as a tourist guide, everything has been fine for him.

Only 3,000 people live on the island. "Two thirds of them work in tourism," says Sofia. "There is also some agriculture, fishing and crafts." In winter, 80 per cent of the shops close. But that's a good thing, because in summer everyone works seven days a week, up to twelve hours a day. Quite a few people have two or three jobs to make ends meet. "We had finally overcome the economic crisis - then came Covid," says Thanasis almost resignedly.

It's not easy for the locals. "I'm here in summer and in winter I go to Austria and work in the ski resorts," says Sofia, who studied tourism. But the 26-year-old isn't complaining. She feels the same way as her father: "Coming home," she says, "feels great every time!" A typical island fate, this alternation between home and away. You often hear life stories like this. And it's great that the Greeks are so open about it. You can't help but grow fond of them.

No wonder half the crew want to stay on Patmos, the landscape is so spectacular, the people so friendly, the food so good. But the wind! Tomorrow the Meltemi is supposed to go to sleep for two days. And that doesn't suit us at all, because we're planning a long trip: 50 miles to the south-south-west to Astypalea, one of the most remote Dodecanese islands.

From Patmos to Astypalea

It's going to be the perfect sailing day. A clear course, the boat constantly travelling at around eight to ten knots. And always this bright blue sky, not a cloud for a fortnight. Butterfly Island soon emerges from the summer haze. Two large land masses, connected only by a narrow isthmus in the centre, gave it its name. At sunset, we fly around the Eastern Cape on the Beneteau. After two days in the harbour, it's time for a night at anchor. Bathing, cooking, relaxing. Agrilidi Bay is made for this: it cuts deep into the land, offers perfect shelter and a picture-perfect anchorage on turquoise waters. A chapel, as is so often the case here on the islands, and an old abandoned farmstead frame it. Now, in the high season, we are the only yacht here. You never have to worry about finding a place at this time of year, late June, early July.

The entrance to the city harbour the next day offers a spectacular panorama: the city rises up like an amphitheatre on a steep mountain, with windmills and a fort on top of the ridge. It is as if you are travelling by boat into a snow-white mountain face. The town is like a decelerated miniature of Santorini: the houses seem to be glued to the rock, the climb up the stairs into the winding old town centre of whitewashed cube houses is a sweat-inducing experience. Once at the top, at the foot of the eight windmills, you have a fantastic view over the harbour. In the evening, the walls are illuminated - a fabulously beautiful picture. After dinner, we end up in the "Athelis" cocktail bar with a view of the harbour bay, in which an illuminated mega yacht floats.

The next morning, the fishermen on the pier attract attention: They have carelessly thrown a large but strangely angular fish onto the pier. But none of the cats or seagulls dare touch it. A fisherman sees my astonished look and tells me. "It's a poisonous puffer fish that was brought here from the Red Sea. They are multiplying explosively and eating away fish and squid!" Worse still, they have four monstrous incisors that are so powerful that they can bite through nets and even small fishing hooks. This is how they eat away the fishermen's catch and make big holes in the nets. Natural enemies? None.

Astypalea and its beautiful bays in the south-east are definitely worth the long journey here. The people seem deeply relaxed, have time and are always up for a chat. There are no crowds of tourists here like on Kos or Patmos. Somehow it's hard to tear yourself away from the island.

As we have two sailing weeks, we even have time for a detour to the two islands south of Kos after the northern islands of the Dodecanese: Tilos and Nisyros. The latter also has its own history: that of volcanic fire (see below). A cruise here is never boring. Especially as the Meltemi is picking up again. So once again "Salty Lipps".

You can find even more information from YACHT.DE about sailing in Greece here:

Precinct information

Journey

Direct charter flights to Kos from various German airports. The island has been very popular for several years, so it is best to book as early as possible. The transfer to the base takes about 40 minutes and costs just under 40 euros.

Charter

We were travelling on an Oceanis 46.1 from the Greek family-run company Istion. Once started in Kos, it is known for very well-maintained ships. Istion has nine bases in Greece, two in the Dodecanese (Rhodes and Kos); we started from Kos. A very diverse fleet of yachts (Jeanneau, Beneteau, Hanse, Bavaria) and cats (Lagoon) are available there. The Oceanis 46.1 (built in 2021) costs 3,400 to 7,050 euros per week; a ten per cent discount is often granted. Information and bookings can be made via the German agency Barbera Yachting, Schweinfurter Str. 9, 97080 Würzburg, Tel. 0931/73 04 30 90.

www.barbera-yachting.de

Wind and weather

The Dodecanese is a classic Meltemi area from mid-June to September. The wind blows very consistently from north-west to north at 4 to 6 Beaufort. It is strongly influenced by the topography of the islands, there are many jet and cape effects and downslope winds on the mountainous sides of the islands, for example south-east of Kos. Strong wind phases with 6 to 8 Beaufort are also possible, which last for a few days. The important thing in the northern Dodecanese is: if you want to head north, sail against the Meltemi on the wind, preferably at the beginning of the trip, and later move comfortably southwards with rough winds. Don't plan any long northerly routes for the last three days, as this can lead to violent blows and frustration. In the early and late season there are often lighter winds from the south-east. The best weather forecast is the Greek one, as it partly takes into account the topographical effects (also available via app).

www.poseidon.hcmr.gr

Harbours and anchorages

Hardly any marinas with mooring lines (Kos and Lakki on Leros), otherwise town harbours with piers, where bow anchors are moored with the stern. Water and electricity are always available, but sanitary facilities are still the exception. On the other hand, the mooring fees are the lowest in the Mediterranean. We usually paid around 15 to 30 euros per day for our 46-foot boat - in the high season. There are many well-protected anchor bays, with a few exceptions where there are also a few buoys, only Panteli on Leros was chargeable.

Navigation and seamanship

It gets deep quickly away from the islands, which makes it easier to plan the trip. There are few shallows, but no major buoyage either. Foresighted reefing is recommended, especially with cape and jet effects. Sometimes the harbour manoeuvres are more challenging in strong crosswinds. In this case, sail quickly and it is best not to furl the chain at the bow by remote control, but to open the winch with the crank handle and let it out quickly and in a controlled manner.

Literature and nautical charts

- Rod Heikell: Greek coasts, Edition Maritim, 69.90 euros.

www.delius-klasing.de - By far the best nautical charts for the area are the Greek pleasure craft charts from Eagle Ray, which also contain harbour plans and weather information. Good availability online via:

www.hansenautic.de

What else you can know

The bow of fire

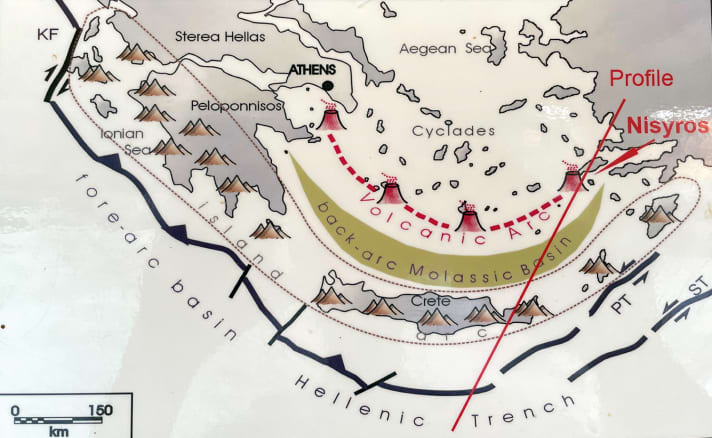

Those who sail in the Dodecanese often don't realise that they are sailing in a belt of volcanically active islands. The islands of Nisyros, Santorini, Milos and Methana, all of volcanic origin, lie in an arc along a tectonic fissure on the seabed.

The crater on Nisyros may not be quite as spectacular as the one on Santorini, which was torn apart by a huge eruption, but the island is definitely worth a visit: it lies south of Kos and has a deep crater coloured yellowish by sulphur, in which the sulphur gases rise up, bubbling and smelling foul. There are several hot springs all over the island, formerly used for spa clinics. The tour to the crater can be explored by moped, especially as the island is otherwise beautiful. The main town of Mandraki with its monastery high up on the mountain, winding alleyways and a beautiful waterfront promenade with bars from which you can enjoy a fantastic sunset is well worth a visit. From there, the more adventurous can drive anti-clockwise round the island via the south-west to the crater. Fantastic panoramic views, but for about one or two kilometres the route is on gravel paths that can only be covered at walking pace. Rather something for fitter riders!

Wine growing on Lipsi

It is typical of the Greek islands that grape varieties that are virtually unknown in the rest of the world have been cultivated on them for many generations. Wine is often only grown for regional consumption on small plots of land; the quality was often considered mediocre. However, this is changing here and there, and some young wineries, especially on Santorini, are now internationally recognised for their excellent wines, mostly white.

On the small island of Lipsi, Lipsi Winery has been preparing to write a similar success story since 2013. Manolis Vavoulas and Nikos Grillis, both hobby winegrowers for decades, joined forces and began using the regional red grape variety Fokiano, which had previously been known primarily for its excellent dessert wines, for new wines. A rosé was developed (Ageriko) and a blanc de noir (Anthonero), a white wine made from red grapes, was added to the programme. The wines soon won awards and were even selected for the Greek president's gala dinner to celebrate independence, which was attended by the British royal family. The small but fine winery can be visited on Lipsi by prior appointment for a wine tasting, less than ten minutes' walk from the harbour!