Emergency transmitters: Raising the alarm, searching and finding - a system overview

Hauke Schmidt

· 08.04.2024

All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios

Whether with a small or large crew, a person overboard is always a serious emergency. If you have also experienced how quickly a person who has gone overboard gets out of sight and how difficult it is to find them again, the question of technical aids arises.

There are basically two product classes: Alarm devices that alert the crew that someone is no longer on board, and devices that actively support the recovery process.

Read also:

The various alarm channels

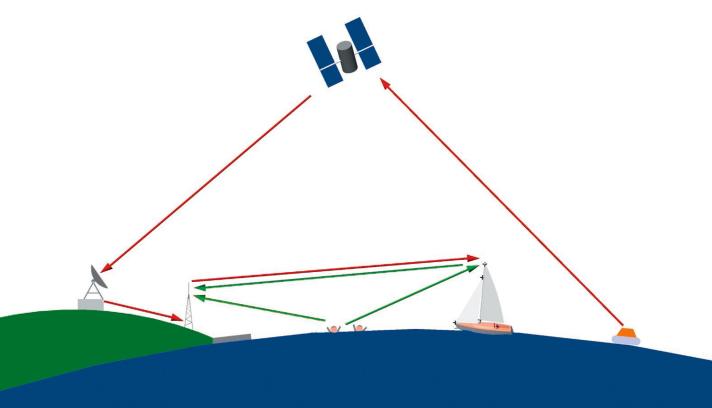

In the AIS system (green), the position data is constantly transmitted directly to all ships within range. Only if DSC is available (yellow) is a direct alert sent to the control centre on land. The Cospas-Sarsat system (red) achieves worldwide coverage through a long reporting chain: via satellite to the ground station, then on to the rescue coordination centre. This processes the case and contacts vehicles that are eligible for assistance

Simple MOB detector

The first group is relatively simple. Each person on board carries a small transmitter, usually similar to a wristwatch. A receiver installed on board analyses its signals. If the connection is lost, an alarm is automatically triggered. The transmitters are known as "tags".

The systems are available with a stand-alone on-board receiver, for example from Nasa, or in conjunction with a smartphone or tablet, which takes over the role of the watch receiver. Current models with this technology come from Olas. The tags work with Bluetooth and contact the smartphone or tablet at regular intervals. If this status message is not received for more than a few seconds, the app sounds an alarm. It also remembers your GPS position. The direction and distance to this location are shown on the display.

At a speed of six knots, a sailing yacht covers a distance of 50 metres in the worst-case scenario between the MOB event and the alarm being triggered. The deviation between the position of the person who has gone overboard and the location stored by the base station is then also this great - which makes it difficult to find them again in waves and uncertain weather or at night.

In addition, the systems are only suitable for raising the alarm on your own boat - nearby yachts are not notified. The usefulness of the system for finding the victim is also limited, as the system only stores the position of the accident. Drift caused by wind and current cannot be detected.

Advantages:

- Safe alerting of the crew

- Low acquisition costs

- Small and handy

Disadvantages:

- No current position

- Alarm only on your own ship

- Alerting only as long as the smartphone or receiver is running

Range:

- Close range around the ship

Cost per person:

- From 70 euros

AIS MOB systems

The second device class consists of AIS MOB transmitters, AIS sart beacons, epirbs and PLBs. They only become active once the accident has occurred. With AIS systems, the person who has gone overboard technically becomes a "boat" and transmits their position as a data record.

All navigation devices that receive this data set report the position of the shipwrecked person. The range depends on the height of the antenna and is between four and 25 nautical miles.

Distress signals were not originally defined in the AIS, they were only integrated later. To ensure compatibility with older AIS equipment, there is no separate data set for distress signals; instead, the transmitters are given a special MMSI that begins with the digits 97. On old plotters, they may therefore be displayed as a ship instead of an emergency.

The AIS emergency transmitters are available as AIS-MOB and AIS-Sart. Sart stands for Search and Rescue Radar Transponder, they are usually activated manually and are intended for the life raft, which is why they are larger and designed for long operating times. AIS-Sart are hardly suitable for convenient carrying on the person.

The compact AIS MOBs can be used for this purpose. They can almost always be triggered manually or automatically. Depending on the model, the latter is triggered either by prolonged contact with water or mechanically when automatic lifejackets are inflated.

However, AIS MOBs are not part of the global maritime distress and safety radio system GMDSS; they are not registered to an owner or a vessel. Their activation triggers various alarms, but not necessarily a rescue operation. Only the manufacturer can be identified using the MMSI.

Advantages:

- Constantly current position

- Alerting of all vessels equipped with AIS in the reception area

Disadvantages:

- It is unclear who responds to the alarm

- Battery replacement usually only by the manufacturer

Range:

- Up to 6 nm to ships, up to 15 nm to coastal radio stations

Cost per person:

- from 200 Euro

AIS MOB system with DSC

If you want to ensure that the rescue chain is triggered, you should use a device with an additional DSC function, then an emergency call is sent via DSC VHF radio after the AIS alarm, depending on the device in the so-called closed loop only to preset MMSIs, for example your own ship, or also in the open loop, i.e. to all radio stations. This alarm is then also received by the rescue coordination centre and must be confirmed by them.

From 2025, only devices that also have a DSC receiver to receive the confirmation will be allowed to operate in the open loop. Class M AIS MOBs fulfil this requirement. Side effect of the receiver: The person floating in the water receives feedback when someone has responded to the distress call.

All AIS distress transmitters have a test function, but caution is advised when using them: The navigation electronics commonly used for pleasure craft clearly distinguish a test message from a genuine alarm and display this accordingly. However, rescue control centres and commercial shipping sometimes use software that cannot differentiate between a test and an emergency because this function is not defined in the standards. To the delight of the person on watch, a sharp alarm is triggered.

Advantages:

- Triggering the GMDSS rescue chain via DSC

- Constantly current position

- Alerting of all vessels equipped with AIS in the reception area

- Alerting your own yacht

- Feedback that the alarm has been acknowledged

Disadvantages:

- It is unclear who responds to the alarm

- Battery replacement usually only by the manufacturer

Range:

- Up to 6 nm to ships, up to 15 nm to coastal radio stations

Cost per person:

- from 200 Euro

Epirb and PLB

Emergency Position-Indicating Radiobeacons, Epirbs for short, are also intended for ships or life rafts and transmit the distress message with position information to the rescue coordination centre via satellite. They therefore always trigger a rescue operation that is coordinated from land. As a smaller version for the lifejacket, the emergency radio beacons are called Personal Locator Beacons or PLBs.

Both work with the Cospas-Sarsat system. Here you enter a completely different world: in contrast to the AIS-MOB, the purpose is not to directly address the ships in the vicinity, but to alert the responsible rescue coordination centre (MRCC). Ships that could help are only specifically addressed by the MRCC in the second step and only receive the coordinates of the person to be rescued in this way.

Epirbs and PLBs send their identity and current position to the control centre. However, vehicles on site cannot listen to this message directly.

In orbit, Cospas-Sarsat consists of three layers of satellites: At an altitude of 850 kilometres, five of them pass over the poles and observe the world in strips, so to speak. On the open sea, it is not possible for them to make contact with ground stations over long distances. Received messages then have to be temporarily stored, which means it can take up to four hours for them to reach the control centre.

Alerting via the seven geostationary satellites at an altitude of 35,000 kilometres and other Cospas-Sarsat technology, which flies on GPS satellites at an altitude of 20,000 kilometres, is faster, almost instantaneous. Small PLBs can sometimes only penetrate as far as the low-orbit satellites. All satellite transmitters must be registered. In Germany, registration takes place at the Federal Network Agency.

The MMSI issued there must be programmed into the emergency transmitter by the dealer. Personalised registration is currently not possible in Germany; anyone wishing to use a PLB on a charter ship, for example, must take the diversions via England and have it registered there.

Personal Locator Beacon (PLB)

Advantages:

- Triggering the GMDSS rescue chain

Disadvantages:

- No direct alerting of ships in the reception area

- Usually no automatic activation

- Battery replacement usually only by the manufacturer

- Can only be registered with a diversion via England

Range:

- Worldwide function

Cost per person:

- from 400 Euro

Emergency Position-Indicating Radiobeacon (Epirb)

Advantages:

- Triggering the GMDSS rescue chain

- Emergencies can be specified (fire, leakage, robbery) and information on the emergency situation can be transmitted

Disadvantages:

- No direct alerting of ships in the reception area (except for combined devices with AIS)

- Large devices, no personal use or MOB function

Range:

- Worldwide function

Cost per person:

- around 1,000 euros

All content in this security special:

- Sea survival training for emergencies

- Stretch ropes: The correct handling of lifelines

- Lifejackets: 24 automatic lifejackets in a large comparison test (150N & 275N)

- Emergency transmitters - alerting, searching and finding, a system overview

- You should master these MOB manoeuvres!

- Back on board with tricks and professional recovery aids

- Safety check: Inspection saves lives

- Prepared for an emergency: 6 checklists for 6 scenarios

Hauke Schmidt

Test & Technology editor