Whether new or used, nothing works on a sailing boat without ropes. Nevertheless, the ropes on many yachts lead a sad existence. Even the basic equipment is often skimped on. If the shipyard chooses inexpensive polyester products for the halyards instead of expensive heavy-duty fibres, the costs are at least halved. The tempting thing is that the cheap lines look just as good on the outside as the high-priced products. When new, they sometimes feel even smoother.

This also has consequences for retrofitting. Those who allow themselves to be overwhelmed by the wide range of products on offer from the equipment suppliers are literally missing the mark. Even the manufacturer's labelling is of limited use. Especially in the lower price segment, ropes are often recommended for all possible uses at the same time. This is not fundamentally wrong, but disillusionment follows when sailing. Just set, the luff sags in the first gust, forming ugly creases. Worse still, the cloth changes its profile; it becomes more bulbous, generates more heel and rudder pressure - characteristics that slow the boat down and make steering uncomfortable. A spirited turn of the halyard winch restores the original trim, but only for a short time - until the line gives way again. This is particularly annoying if you have just invested in high-quality, low-stretch sails.

On the other hand, always choosing the most expensive rope makes the outfitter happy, but puts an unnecessary strain on the on-board budget. Instead, you should think about the requirements. The more precisely you know what you want the rope to do, the easier it is to select the optimum rope. The material and construction of the lines play a role here. They not only determine the price, but are also responsible for the stretch behaviour, breaking load, abrasion resistance and feel.

Especially in combination with halyard stoppers and winches, a different material mix in the cover can bring significantly better results. In addition, not every halyard and sheet has to be made of Dyneema; sometimes a little more stretch is even an advantage. The situation is similar with mooring lines. Here too, the material used and the braiding of the line have a direct impact on everyday life on board.

Trap rope tow

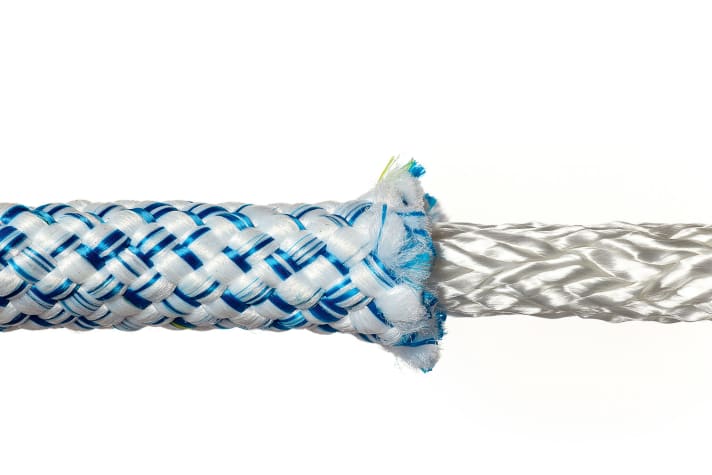

Lines with a Dyneema core are the first choice for the cordage. The cover and diameter must match the fittings.

On a yacht with a mast height of 13 metres, there is about 15 metres of line between the halyard stopper and the headboard when the main is set. Cheap Dyneema ropes stretch by about 2.3 per cent when set, so 35 centimetres more rope must be pulled through to achieve the target tension. With additional wind pressure, however, the elongation only increases by 0.1 per cent, so the halyard sags by just 1.5 centimetres. Even a good polyester rope would sag five times as much. The good values of the Dyneema fibre can be further improved by so-called hot stretching. In this process, the braid is compressed, which increases the breaking load and further reduces elongation. As the fibre is UV-stable, insensitive to kinking and abrasion-resistant, it seems to be made for sailors. But there are also downsides. The extremely smooth surface requires special coatings or rope constructions with an intermediate sheath.

What the leash should be able to do

- Low elongation: For main, genoa and code-zero halyards, the less stretch the better. With gennakers or spinnakers, however, a stretchy halyard is an advantage. When the windward leech of these sails pops up, load peaks occur that a polyester rope absorbs well

- Robust coat: Halyard stoppers are the rope's greatest adversaries. In addition to the direct load from the clamp, there is the problem of the slipping core. With Dyneema ropes, the core bears the load. However, if it is poorly held in the stopper, the force can be transferred to the sheath, causing it to tear. Coated cores and sheath braids made from Technora, Dyneema or Vectran fibres can prevent this from happening

- Breaking load: The required breaking load depends on the size of the boat, but when using Dyneema, the fittings are more important. The halyards are so tear-resistant that the actually sufficient diameter is too small to hold in the stoppers or to be caught by hand.

Typical constructions

- Parallel core jacket: Standard construction for polyester traps. The parallel core fibres are intended to reduce the elongation of the rope. An intermediate sheath is necessary and often makes the lines stiff.

- Core-shell: Two braids are used here. Polyester or coated Dyneema can be used for the core. The cover is made of polyester, possibly with Technora or Vectran components.

- Core-intermediate jacket: A layer of polyester staple fibre increases the friction between the core and sheath, resulting in fewer problems in the stopper. The additional braiding reduces the core diameter.

Common core materials

- Polyester: Inexpensive and robust, but the material stretches comparatively strongly. Suitable for spinnaker and gennaker halyards.

- Dyneema SK38: Inexpensive fibre. It offers approximately the breaking load of a polyester rope, but has significantly less stretch. A good upgrade for cruising yachts with basic equipment.

- Dyneema SK78: Standard fibre for high-performance ropes, very high breaking load and low elongation. Ideal for performance cruisers and regatta boats.

- Dyneema SK99: Highest breaking load, only interesting for pure racers.

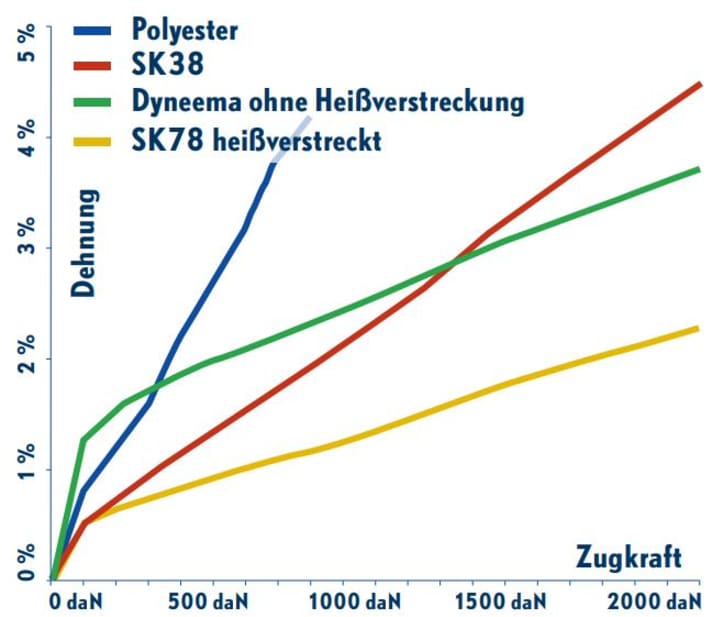

Strain comparison

The diagram clearly shows the material differences: hot stretching reduces the initial elongation in particular. The differences are smaller in the working range around 400 decanewtons. SK38 stretches more, but much less than polyester.

Pods

The area of use and rigging of the yacht determine the optimum cordage.

Cruising boats with large, overlapping genoas or modern performance cruisers with narrow headsails place different demands on the rigging. Despite the relatively large headsail, the sheet loads on a cruising boat are manageable. The diameter of the cordage is primarily determined by the handling and not by the breaking load. Even the stretch is not critical: the long foot of the overlapping genoa leads to flat sheet angles, which means that the shape of the sail changes little, even if the line gives way by four centimetres in a gust. The situation is completely different on a performance cruiser: the narrow-cut jib reacts extremely sensitively to changes in sheet tension and can hardly be trimmed with a stretching rope. The angle of attack and twist change with every increase or decrease in wind pressure.

What the leash should be able to do

- Low elongation: The slimmer the sail and the higher the load on the line, the more you should invest in low-stretch ropes. The stretch does not play a significant role in the case of heavily underset mainsheet buoys or large genoas.

- Robust coat: Curry cleats and winches put a strain on the mantle. On many modern boats with a single-handed layout, the sheets are even clamped off in halyard stoppers, in which case the coats suffer particularly.

- Lehnig: A stiff, kinking genoa sheet messes up every turning manoeuvre, so the line should remain as supple as possible. Polyester ropes have the advantage of hardly hardening even under heavy loads. Dyneema cores can become very stiff.

- Handy: The sheet should not be too smooth. But whether the fluffy feel of a staple fibre is necessary is a subjective decision.

Jacket constructions

- Grib-Faster: One-to-one braiding results in a handy cordage. Specially treated continuous polyester fibres or added staple fibres result in a robust cover that is still easy to grip.

- Continuous fibre: Sheaths made from 20-plait continuous polyester fibres are durable and can cope well with winch drums and curry clamps. They produce a supple rope, but are comparatively smooth.

- Staple fibre: The fluffy, soft coats made from staple fibre or worsted yarn are classics. They feel good in the hand, but wear out much faster. They are not recommended for winch use.

Core materials

- Polyester: The favourable material is okay for overlapping genoas and hand-operated main bulkheads on cruising yachts, it remains supple even after heavy use.

- Dyneema: The low stretch of SK38 or SK78 is particularly necessary on performance cruisers. If you want to taper the sheet for gennakers or spinnakers, you should use coated SK78; the bonded fibres are more robust and easier to work with.

- Mixtures: To save costs, the Dyneema fibre is partially mixed with polypropylene. This reduces the breaking load, which is not critical for sheets. Elongation increases only slightly.

On the winch

Depending on the drum surface, winches can be real rope eaters. This can be remedied by sheathing braids with admixtures of Technora, Dyneema or Vectran. However, the latter is not UV-stable and disintegrates over the years.

Mooring lines

Land lines must be robust and stretchy. The material is crucial.

For more than a third of the year, the fate of the yacht depends solely on the mooring lines - the ropes are therefore one of the most important items of equipment on board, even if they are rarely considered as such. Polyester and polyamide, also known under the brand name nylon, are the most commonly used plastics. Polypropylene, which is also available, is more sensitive to light and abrasion and should only be used if the line needs to be buoyant. Ropes made from polyamide have a clear advantage, offering up to 10 per cent more stretch than the best polyester ropes. However, for a long time another material property stood in the way of this: polyamide absorbs significantly more water than polyester, with the result that the fibres shrink. After a short time, the lines became stiff and unwieldy. The rope makers have now largely got the problem under control.

What the leash should be able to do

- High elongation: The more energy the line can absorb by changing its length, the softer the ship jerks in, which reduces the load on the cleats and makes the stay on board more comfortable.

- High breaking load: The required breaking load depends on the size of the ship. Even small chafe marks weaken the cordage considerably, so a reserve should be planned in.

- Robust: Rusty iron rings, concrete quays or the lip nozzles with cast iron seams: The list of possible chafe marks is long. The swell and wind mean that the mooring lines are practically always in motion. Only very robust constructions can withstand this constant stress.

- Lehnig: The smoother the line is, the better it can be covered and shot up.

Constructions

- Beaten: Lines made from three carded ends are the classic. The construction is favourable, easy to splice and stretchable. However, the cordage is not very stretchy and can form kinks.

- Squareline: Four interwoven carding elements produce a very supple, stretchy rope that is easy to cover and stow. The rope does not kink, but tends to pull threads.

- Core shroud: The structure corresponds to a sheet, resulting in a very robust and supple rope. The stretch depends on the material, but is generally somewhat less than with a square line.

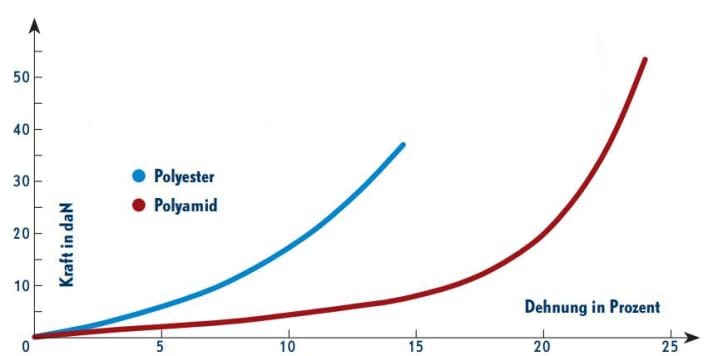

Elongation and breaking load

The curves show two square lines. The polyamide version stretches more strongly and has a higher breaking load. The crew can sleep more soundly in two respects: the yacht jerks less hard, and if the line chafes somewhere, it has more reserve.

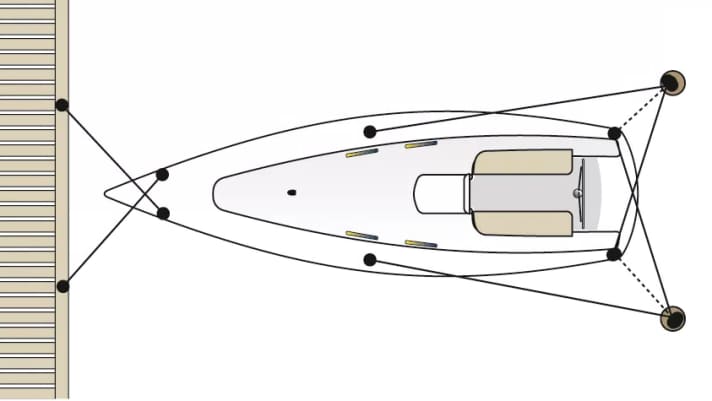

Diameter and length

The size of the mooring lines depends on the size of the ship. For a ten-metre yacht with a displacement of four to five tonnes, 12 to 14 millimetres is appropriate. There should be at least six lines on board, two as stern lines roughly corresponding to the length of the ship. Mooring lines twice the width of the boat are usually sufficient at the bow. The two additional lines serve as manoeuvring or shore lines in the pack. Double the length of the boat or more does not hurt.

Single braids made from Dyneema

Sheathless Dyneema lines are stronger than wire and can be used in many different ways.

Dyneema fibres are not only highly UV-resistant, but also smooth and abrasion-resistant. Lines made from these fibres therefore do not require a protective cover. These single braids can be processed into rope shackles, for example, and in combination with aluminium thimbles can replace expensive deflection blocks or even complete backstays. Or they can be used as soft rigging to give old rigging techniques a new lease of life.

What the leash should be able to do

- Rope shackle & lashing: The connectors are not critical and can also be spliced from a trap core. Compact braids fray less. However, they should be coated so that the fibres stick together

- Forerunner: In principle, long, low-stretch braid lengths are advantageous. If the rope runs over blocks, it is better to choose a compact braid

- Backstay: Long braid length, coating and hot stretching are optimal, they minimise stretching

Constructions

- Short braid length: With this twelve-plait braiding, the fibre strands run at an angle of around 60 degrees. This results in a compact, round rope that runs well through blocks.

- Long braid length: Also a twelve-plait braid. However, the fibres lie flatter, which means that the rope stretches less, but also flattens more quickly and can jam in a block.

Hot stretching and coating

- Compressed: In order to optimise elongation behaviour and breaking load, the ropes are hot-drawn - in the case of Robline's Stronger-than-Steel series to such an extent that the fibres behave almost like wire.

- Glued: The fibres are bonded together with a polyurethane coating. The mesh holds together better and is even more robust. The coating can also be applied retrospectively.