On this morning in January, the sun is shining over the Costa del Garraf. Two men are drinking their cortado in front of one of the cafés down in Sitges harbour and wave briefly as Tobias Wuttke walks across the jetty. "Hola Tobias, buen dia!", the two shout. Wuttke - jeans, cap, sunglasses - waves cheerfully and greets them back; they know each other in the pretty little marina. They know each other from sailing, from sharing cervezas in the bars, from the many anecdotes that have been doing the rounds for years. Palm trees line the promenade, and seafood is served in front of the restaurants from lunchtime. The two Spaniards want to know if he wants to go sailing. "Si, claro," Wuttke calls back. The wind is good, the weather is marvellous. Then he goes to his classic.

The Spanish sailors from Sitges have long since stopped wondering about this man called Wuttke - a German. Does what he can't stop doing. Obsessed with craftsmanship, a perfectionist. Everything has to fit and sparkle, especially when it comes to his favourite boats.

A special boat in the harbour- today's classic stands out

Wuttke's boat was also the main reason why the Spanish initially thought he was crazy when he first turned up in Sitges 20 years ago with his legendary Zossen. A classic with a metre-long bowsprit and unfurled red sails was suddenly bobbing in the harbour. Small cabin, portholes and cleats made of bronze and galvanised steel, wooden blocks. There was no winch to be seen anywhere on board, the halyards and sheets looked as if they were still made of hemp like a hundred years ago - a boat like a relic from the days of the old tar jackets. The craziest thing under the hot Spanish sun was due to this fact: The vessel of the new sailor named Wuttke was constructed entirely of wood. And the Mediterranean sailing enthusiasts were also amazed at the year of construction: 1914.

Other interesting classics:

Wuttke, 61, jumps aboard his classic, the "Molly Q". Today, the aged treasure floats perfectly restored in the water and is one of only two classics in the harbour. Wuttke takes the cap off his head, opens the companionway hatch and says: "Owning a wooden boat here is an absolute exception." He climbs into the saloon of his small yacht. It's cosy, a patinated paraffin lamp dangles under the skylight, the green front of a classic Danish Sailor radio is mounted on a bulkhead. You are immediately immersed in a bygone era of sailing. The two cushions on the bunks - in the design of the English Union Jack - emphasise what you are dealing with here.

The "Molly" used to be a workboat

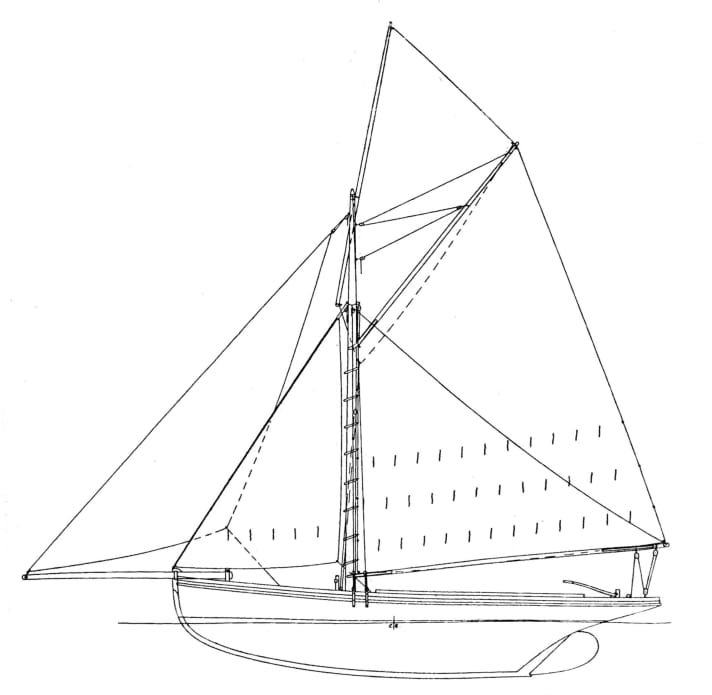

The "Molly Q" is an English classic of a special kind, a Morecambe Bay Prawner, also known as a "Nobby" or "Half-Decker", whose crack and construction originate from the old fishing boats from Lancashire. A tough working boat that the British used to fish for crabs, it was designed and built as a yacht by the Crossfield & Sons shipyard. The long keel runs deeper and a cabin is set on the flat deck. However, the small sailing ship has never lost its essential characteristic with this variant: speed.

Wuttke heaves two sail bags out of the foredeck as he continues. Of course, he knows every millimetre of the history of his shrimp runabout. In the days around the turn of the last century, fishermen used to go out on the north-west coast of England to fish for the coveted shrimps. They only had one tide for each catch and had to get out as far as possible on the rising tide and back in as quickly as possible on the ebbing tide.

They cooked the crabs they caught on board during the journey home, squatting down in the forecastle next to a steaming cauldron, and often in the large cockpit next to a coal-fired hob. Because whoever was the first to offer their catch in the harbour got the most money. And the fresh shellfish fetched good prices. Back then, potted shrimps were a delicacy. The boiled pink shrimps were served with tea, marinated in herb butter and presented in a clay pot.

The ship had to fulfil the requirements

The fishermen raced through the tidal waters in wind and weather, shot across the sands and, in addition to courage and sailing expertise, needed one thing above all: fast, manoeuvrable boats. This gave rise to the racy Morecambe Bay prawner type, and these sailing fishing boats can still be seen in old photos today: wooden flounders at sea, slim and long, equipped with a sheer, flat deck and a completely over-rigged gaff rig. The boom extends far beyond the stern, two foresails fly in the wind at the front, while the three-metre bowsprit juts out to sea like the snout of a sawfish. The boats were used between the Solway Firth and North Wales and were also known as "shrimpers" or "smacks", depending on the region. An old report says of them: "The boats are stable, fast and capable of sailing below 50 degrees on the wind as they race through the winding channels and cross seas."

So it was tough sailing, while the boats also pulled nets through the water while trawling. But the effort was worth it. The shrimp business was booming at a time when seaside resorts were becoming increasingly popular on the English coast and high society was discovering life on the beach and recognising it as a fine English way of life. For the sailing fishermen, however, working in the raging tidal currents often turned into a breakneck adventure.

The classic is in its original condition

A photo from 1897 shows the pretty boats after an operation at Southport Pier north of Liverpool. The prawners lie close together, looking like a battered rugby squad after a mud fight. The sails are hanging at half-mast, men in caps and dark jumpers are doing gymnastics on the decks, soaking wet from the sea water. A small reminder of what sailing meant for centuries: it wasn't fun, it was a back-breaking job.

A good 120 years later. Tobias Wuttke sets sail in sunny Sitges. "The boat should look pretty much the same as it did back then," says the German. "No winch, no modern Curry clamp, most of it is original or modelled on the old one." At that moment, a Frenchman comes walking across the jetty, Jean-Charles, a Breton who is the second person in the harbour to make the effort to preserve an old wooden boat. The two of them are aware of their exotic status down here and don't call themselves "partners in crime" for nothing. Two who cherish and care for their classics; two who stick together in the Spanish fibreglass modernity, ironclad or rather: wooden.

Jean-Charles had just separated from his wife four years ago and was standing down at the harbour with his belongings when an acquaintance from England offered to sleep on his boat for a few nights. Jean-Charles accepted, fell in love with his sailing home on the spot and promptly bought it from the acquaintance: a 10.50 metre long English gaff cutter built in 1936, which he has called his own ever since. He and Wuttke now know each other well and usually work together on their old ships. An infernal duo in dapper Sitges, who often walk along the jetties with paint-smeared hands. And today they both want to sail. Each on their own yacht.

Sailing on the "Molly" is originally

As soon as the sails are set outside, the almost ten-metre-long Prawner picks up speed. With a wind force of three to four, it runs through the blue waves at half wind, soon rushing along at a good eight knots. Even modern yachts in this length category are likely to give the old shrimper a run for its money, and most of them simply sail away. Jean-Charles, who is sailing abeam with his gaff cutter, is also left behind. Meanwhile, on board the "Molly Q" is Bart van Dijk, a Dutchman who has skippered several times in the Fastnet Race, has skippered hundreds of yachts in his life and competed in dozens of regattas; a friend of Wuttke's who is now second in command. "The boat is not only beautiful and fast," says van Dijk. "After 25 years of sailing with electronic instruments, hydraulic pumps and all kinds of modern gadgets, it feels like a liberation to feel the origins again. The 'Molly' is an elemental experience. Pure sailing, no frills."

The long boom is reflected in the skylight, the halyards hang open on the mast as the boat heels and picks up speed again in a gust. With hardly any pressure on the tiller, the old Prawner seems to move effortlessly against the backdrop of the Costa del Garraf. Amazingly light and agile sailing - something the English already experienced 170 years ago.

As early as 1849, Francis John Crossfield decided to take part in the good seafood business. He switched from carpenter to boat builder, founded a shipyard and began to mass-produce the fast prawners. The fishermen virtually tore the boats out of his hands, while the tidal speedsters were constantly being refined.

The long journey of the "Molly"

However, the many years of experience with the vessel paid off not only in fishing. When the "Molly Q" slipped into the water as a yacht in 1914, its first owner, a Dr Edmondson of Lancaster, soon won the first regatta with it: In the same year, the Prawner "Molly" took first place in the Midnight Race to the Isle of Man.

Several owners owned the classic over the following decades, sailed it in regattas and used it for excursions. The yacht survived the Second World War docked on the Ulverston Canal and then came to Fleetwood, where a cinema operator bought her. In 1950, she won another regatta to the Isle of Man - now christened "Nahula". The boat fought its way through a nasty storm that swept across the Irish Sea and was the only one to reach the finish line.

Another change of ownership was imminent: in 1980 - now 66 years old - the brave shellfish sloop came to Suffolk. The boat was sailed there for almost two more decades until a German saw it in 1997: Tobias Wuttke - it was to be his first own ship. He had wanted one just like it: "I've always found gaff sails the most beautiful, their shape, the way they give form to the rig, to the whole ship."

In the nineties, the current owner came across the classic

The fact that he had his sights set on a classic, preferably an English one, may be due to his early experiences. Even as a young boy, the Hamburg native sailed with his father on the "Atalanta", the former pilot schooner "Elbe 1", built in 1900 at the Peters shipyard. At the age of eleven, he finally learnt to sail himself at Bosham Sea School near Chichester, which he soon attended - without speaking a word of English. He then joined the sailing team at boarding school, ultimately as its captain, sailed regularly with his father on the Baltic Sea in the summers, later crewed a Swan 42 from Kiel to A Coruña and completed many trips in the Mediterranean as an adult.

In 1997, the time had come: Wuttke, who was now living in Paris, was looking for a boat of his own. Nothing off the peg, rather something exotic - old, British. To be more precise, it had to be an English gaff cutter with rust-coloured sails. He discovered the seasoned Prawner in an advert in an English classic magazine. Wuttke then travelled to Woodbrige in Suffolk, saw it, immediately started dreaming, commissioned a surveyor, stopped dreaming - and bought it. In the spring of 1997, he rechristened the boat with its old name and began initial work on the classic.

Not everything is rosy on board the "Molly"

During a stormy trip across the Channel, he first brought his classic "Molly Q" to Saint-Valery-sur-Somme in Picardy and rebuilt the entire interior in the first summer, as it was no longer original. A New Zealand boat builder helped him and lived on the ship during these weeks. New insights followed: Various deck beams and the rudder coker were rotten. Wuttke sailed the ship back to England, where the entire deck was replaced at Combes Boatyard in Bosham. It took several weeks, during which Wuttke himself lent a hand. A skylight was added, an extended sliding hatch and a customised diesel tank under the aft deck. A marvellous summer followed with weekend cruises along the French Atlantic coast, followed by a long trip via Guernsey to Douarnenez. But woe betide anyone who thinks that an almost 100-year-old wooden boat is a comfortable life partner.

When stripping the underwater paintwork the following winter, Wuttke discovered that many of the nails in the hull were rusty and some of them were literally falling out of the planks as millimetre-thin pins. So the next big job was on the agenda: the restoration of the hull, which involved replacing almost all the frames and frames as well as all the planks below the waterline. However, this now took place in Vilanova y la Geltrú, Spain, as Wuttke had moved south in the meantime - and so, of course, had the "Molly Q", which travelled there on a low-loader. New centre of life: Sitges, south of Barcelona, where this beautiful harbour was just around the corner and the ship could be restored just a little further south in Vilanova. The work was carried out by a young English boat builder, and all the materials were imported from England to match the original: grown oak knees for the ribs, sawn larch for the planks, forged galvanised "Rosehead" boat nails, plus the necessary tow, plus a few loads of old red lead for putty and the first underwater paint - everything was to be as it was back then. And when this was finally over, Wuttke sailed into his new harbour for the first time. It was the moment when the jaws dropped in Sitges.

Out on the water, Wuttke is still cruising. It's a creamy day and the Prawner, now a proud 107 years old, is still sailing lively on the wind. Anyone who asks Wuttke while sailing what else he has done to the ship will receive a long list of answers. In 2006, the boom and gaff were replaced, both made in England, of course. As was the new mast, which was due in 2019.

Tobias Wuttke recently laid new teak in the cockpit, renewed the running rigging and replaced several blocks with historical originals. "An old ship is an obligation," he says, "just like in the old days."

This article first appeared in YACHT 14/2021 and has been revised for this online version.

Technical data "Molly"

- Shipyard: William Crossfield & Sons

- Year of construction: 1914

- Construction method: Karweel, larch on oak

- Length above deck: 9.80 m

- Waterline length: 7.90 m

- Width: 2.80 m

- Draught: 1.50 m

- Weight: 8.0 tonnes

- Sail area: 61.0 m²

- Sail carrying capacity 3.9