Mistral 33 "Piano": From sea cruiser to retro classic - a piece of jewellery

Lasse Johannsen

· 26.02.2023

It's one of those summer evenings that sailors can't help but daydream about. Frank Schamuhn is moored in his "Piano" in the Dyvig on Alsen when a retro classic comes in. Classic lines over the water, a beautifully even deck with recessed hatches and fittings, the owner's eye, sitting casually in the director's chair on the aft deck, is the only thing that catches the eye as it wanders over the silhouette of the slender sloop with its long overhangs.

A key experience as a starting signal

It clicked for Schamuhn - he couldn't help himself and immediately incorporated the scene into his daydreams. Today, he says that this moment was the catalyst for what he now looks back on with satisfaction: the restoration of his Mistral 33, built in the early 1970s in Ellös near Hallberg-Rassy - an almost two-year cure, during which he not only spent more than 1,000 hours restoring the substance and cosmetics to new condition, but also adapted the design of the classic to his dreams from the Dyvig.

"I hope Olle Enderlein isn't turning in his grave," says Schamuhn and laughs. It's the start of the season, the first since the work was completed. Schamuhn and his family crew have already moved the "Piano" from Bremen to its summer berth in Gelting. Now it's time to harvest the labour, and as the owner gives a tour of his classic, he himself marvels at what he has touched in the past two years: "actually everything".

The classic was almost on the family's sales list

The decision to realise his daydream came at the right time. The sale of the Swedish sea cruiser, which seemed to be too small for the whole family, had been planned for years. But the longer the sales efforts dragged on, the older the children got and the more conscious they became of the realisation that the "Piano" would one day be quite enough.

A broken ankle suffered by his wife finally set the ball rolling in summer 2019. The season is over for Schamuhn. He declares the sales endeavours to be over, moves the "Piano" to Bremen, has it refloated in mid-August and sets about adapting the classic to his ideas in a comprehensive refit.

Schamuhn has concrete ideas and the retro classic Spirit 50 in his mind's eye. "I'll never be able to afford it, but I wanted to get in that direction," he says looking back. Above all, however, the owner knows his classic and its weak points and knows what needs to be done to prepare the "Piano" for a second life, not just its appearance.

The Schamuhns have been at home on board since 2006, with their summer berth in Grömitz harbour until shortly before the restoration. From here, they sail around the Bay of Lübeck on summer weekends, travelling around Funen or to southern Sweden on summer cruises. The sons grow up on board. It's the typical life of a sailing family, and that includes the winter months.

Schamuhn has already taken many things in hand. "When we bought it, the classic was in a pretty desolate state," he says looking back. Over time, the Schamuhns renewed the upholstery and the teak deck, stripped off all the paint, but, as the owner emphasises, at the time it was still "under winter conditions and quite amateurish". They painted the hull, veneered the floorboards, renewed the on-board electrics and technical equipment and added a refrigerator and hot water boiler.

A major construction site for the "Piano": the engine

Initially, the old Volvo Penta from the year the Mistral was built was a perennial issue. "It occasionally broke down," recalls Frank Schamuhn, who spent a lot of time on repairs. "Until we replaced it at some point." At the time, Schamuhn opted for an identical engine. It was completely overhauled and converted to dual-circuit cooling.

This morning too, the old MD 11 C starts up without a long organ and creates a ship-like atmosphere with its solid sound and typical odeur as it leaves the harbour. The sails are set quickly, and in the light wind the Mistral runs as if on rails. The large cockpit invites you to stretch out and make yourself comfortable, and the retro classic radiates the feeling that it could now go straight ahead for a few days.

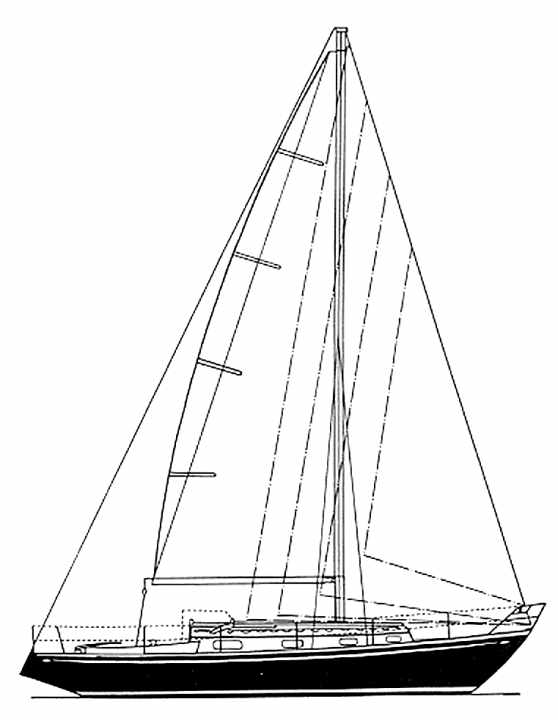

This is not the only reason why the Mistral is a typical representative of the West Swedish sea cruisers from the sixties. Her lines also identify her as such. This is because designer Olle Enderlein characterised the nature of these "Havskryssars" at the time. Their lines above water are reminiscent of the designs of Sparkman and Stephens, while Enderlein's designs remained traditional under water.

This period marked the transition from traditional boatbuilding to GRP series production. Harry Hallberg had left the shipyard he had been running in Kungsviken on Orust since 1943 and moved into a large new building in Ellös. The P 28 with plastic hull and the 24-foot Misil, which had been built since 1955, were to be made entirely of GRP here. And it became possible to build a larger model.

The clever, modern design is the strength of the "Piano"

Hallberg turned to Olle Enderlein, who designed the 33-foot-long Mistral for him in 1966. The hull, deck and cockpit were made of GRP, the decking of teak rods and the superstructure of mahogany. The result was a combination of the best of both worlds. An easy-care and structurally hardly susceptible hull and the appearance of classic sea cruisers.

The designer and shipyard hit the bull's eye with the Mistral 33. Under water, the classic has a split lateral plan with a large skeg in front of the rudder. Although Enderlein never built a trim rudder, and the massive screw well was already old-fashioned in the year of construction, the design passed as modern and was advertised as such.

The mast is far forward, which results in a relatively small foresail triangle for the top rig and a correspondingly wide mainsail - this explains the Mistral's proverbial tendency to windward. In fact, some owners have changed the rig plan or modified the lateral plan between the keel and rudder to alleviate the problem.

The Mistral 33 becomes a cult, but its construction is too costly

The appealing design quickly acquired a real cult status, from which the now 40 to 50-year-old used classics still draw today. A total of 216 units left the shipyard between 1966 and 1975, and several were exported to the USA. It was the peak of Harry Hallberg's success, who sold his company to Christoph Rassy in 1972. From then on, he traded as Hallberg-Rassy and continued to produce the Mistral in Ellös for a further three years.

However, it cannot compete with the success of the Rasmus 35, which Rassy has been building entirely from GRP since 1967. "It took more man-hours to build her than a Rasmus 35, although it was never possible to calculate what the Rasmus 35 could do for the much smaller Mistral 33," says Christoph Rassy's son Magnus, current head of the shipyard.

The boat builders needed around six weeks to produce the boat, and it cost the buyer just under 80,000 marks - excluding VAT - in 1975. And when the Monsun 31, also designed by Olle Enderlein and built entirely from plastic, came onto the market in 1974 and turned out to be an instant bestseller, it was clear that the era of composite construction was coming to an end.

Today, enthusiasts are prepared to pay high prices for a well-preserved specimen or - like the Schamuhns - invest a lot of time and money in it. "I started by working on the hull," recalls Schamuhn in the summer of 2019, when he set to work with vigour. He applied Awlgrip with a roller and finishing brush, while a friend helped with the final coat.

Two years of work and great satisfaction on board at the end

Peter Lansnicker is on board today, pulls out his smartphone and shows before and after photos. After this sense of achievement, the Schamuhns set about stripping everything on deck that is under paint down to the bare wood. "And then we thought about the windows," says Schamuhn. He sits at the tiller and looks at the superstructure walls with satisfaction.

Because "the windows" were a major concern and turned out to be one of the most complex operations of the entire refit project. Schamuhn made the new cut-outs after sealing the old ones with solid wood panes. Finally, he veneers the superstructure and installs the new windows, which consume a considerable portion of the entire refit budget.

The teak deck is only a few years old and can be refurbished with little effort. My friend Lansnicker, who now refinishes surfaces on yachts for a living, is again helping with the colouring of the wooden surfaces on deck with Owatrol D1 and D2.

The classic refit affects all areas of the ship

The refit of the classic boat, which has already been lovingly refurbished over the years, is also underway below deck. The bilges are being completely repainted, the lighting is being professionally redesigned - the Schamuhns run a lighting studio in Bremen - and the deck beams are being trimmed from white to natural. "I've always said that if we're going to do it, we're going to do it right," says the owner. And so he finally takes apart the navigation corner, which he has never really loved, to fit it out with contemporary electronics.

In the cockpit, the owner lays a new bar deck on the dents. Then new fittings, a modified pulpit and new railing supports find their place, the pushpit is discarded. Dismantling the rig and having the old aluminium profiles powder-coated is then a piece of cake, but a lot of time is also spent on redesigning the fittings.

The crowning glory is the installation of the recessed hatch on the aft deck. Schamuhn has constructed a nero frame for this, which acts as a water drain and into which the old hatch cover is embedded.

Over the two years, many ideas that he had always had in mind have been realised, says Schamuhn, looking more than satisfied. The aft deck is one of them. It is now flush, and no pushpit blocks the view of other ships. It remains to be seen whether the owner will once again daydream as he did on the Dyvig. He would now have the space for a director's chair on the aft deck on board himself.

Technical data Retro classic Mistral 33:

- Shipyard: Harry Hallberg/Hallberg-Rassy

- Designer: Olle Enderlein

- Total length: 10.18 m

- Waterline length: 7.65 m

- Width: 3.02 m

- Draught: 1.47 m

- Displacement: 5.2 tonnes

- Ballast: 2.4 tonnes

- Sail area: 50 m²

These classic yachts are also interesting:

Lasse Johannsen

Deputy Editor in Chief YACHT