When monohull yachts reach their stability limits, their crews can clearly feel it. The heeling increases sharply, often accompanied by a brilliant sun shot and loudly rattling sails. If there is too much cloth, the boat can overtake so far that it is difficult to hold on to the cockpit, let alone furl the genoa and tie in a reef. In other words: orange alert!

If you have already reduced the sail area with foresight, you will only be noticeably laid on your side in a gust. This reduces the wind pressure in the rig, and as soon as it eases, the ship rights itself again. This self-regulation and the ability to communicate at the limit makes keel yachts comparatively easy to handle. This is another reason why they are considered by many to be more seaworthy and safer.

Ride-on cats react differently to monohulls

A heavy, seven or even eight metre wide twin hull hardly heels. Thanks to its dimensional stability, its rig can withstand the force of the gust for much longer. This characteristic is particularly appreciated by beginners and occasional sailors, who often feel uneasy when sailing monohulls.

Static stability in comparison

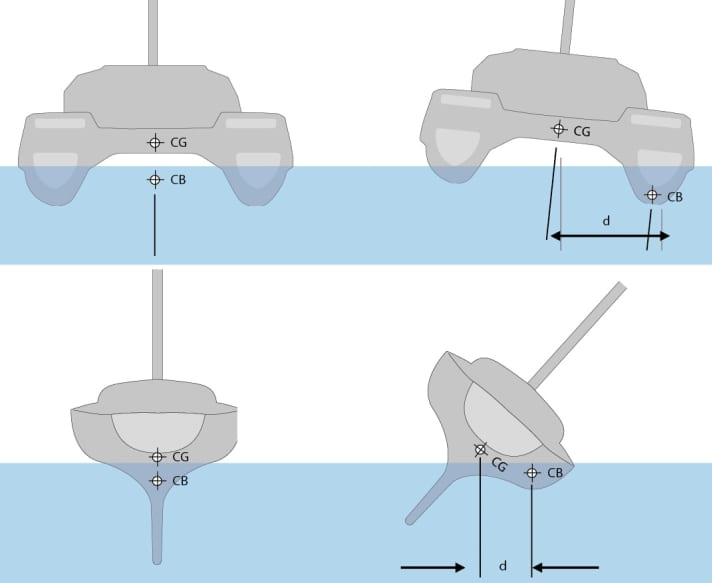

The righting moment (RM) defines how much resistance a yacht has to lateral forces. It is calculated from the product of the weight of the ship and the distance (d) between the centre of gravity (CG) and the centre of buoyancy (CB). In a monohull, both centres of gravity are close together even when heeled. Although the cat hardly heels when sailing, the empty hull is pushed slightly under water by the wind and the centre of buoyancy also moves to leeward. Due to the greater distance between the two centres of gravity, the righting moment of a catamaran is many times that of a monohull.

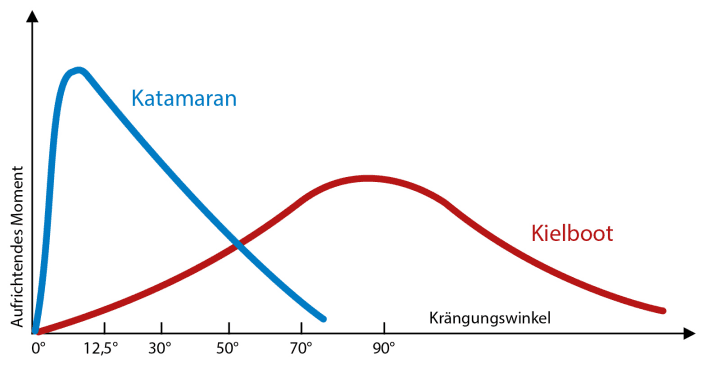

Stability curves

However, the advantage of greater initial stability does not override physics, nor does it replace the need for good seamanship. If the force applied is too great, even multihulls can tip over - not with long notice, but suddenly.

In a monohull, the righting moment increases continuously as the heel increases until it decreases from about 90 degrees and then becomes negative at usually 110 to 120 degrees. In a catamaran, the maximum righting moment is reached at around 10 degrees, after which it decreases rapidly.

This is what happened to the crew of an Outremer 45 in Croatia recently. A squall caused the boat to capsize within seconds. The fact that such a large cruising catamaran can capsize in a comparatively sheltered area such as the Croatian islands revived the debate that has been going on for decades about the safety of multihulls. And it was not the only incident this season.

Although catamaran capsizes are very rare, two other accidents have recently occurred in the Mediterranean and the North Sea. A 13 metre long catamaran capsized at anchor off Corsica in a heavy storm. In mid-September, a smaller cat drifted keel-up onto the coast of Vlieland.

Even if the circumstances and the boats were very different and require a differentiated analysis, the overall picture nevertheless raises fundamental questions:

- Under what conditions can it become critical on catamarans?

- What safety reserves do they offer?

- And how has their design changed in recent years?

Firstly, it is important to categorise the accidents. The catamaran off Corsica, for example, was not an ordinary cruising catamaran, but an extremely lightweight construction from the 1990s. According to the shipyard, the Outremer 43 had an unladen weight of less than four tonnes. By comparison, a Lagoon 42 designed for cruising weighs a good three times as much today. Furthermore, the boat did not capsize while sailing, but at anchor after the wind had reached under the bridge deck with peaks of up to 90 knots.

The cat that capsized off Vlieland was also a lightweight construction, and an extremely compact one at that, with a hull length of just eight metres. The French-built Rackham 26, which was available in a basic and a regatta version until it was discontinued, is more of a sports catamaran than a touring catamaran and does not fulfil the CE requirements for offshore use. In the stormy conditions that were its undoing, it simply had no place in the choppy North Sea.

When does a catamaran capsize?

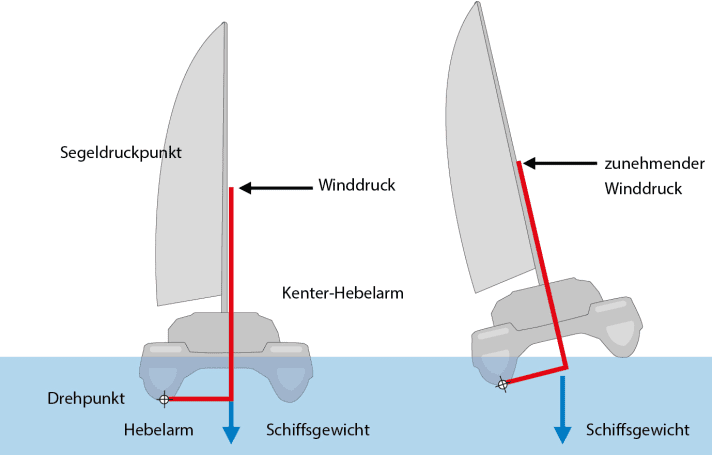

How much wind or wave does it take to exceed the stability limit? The physical background to stability is quite simple to outline: A boat that experiences a lateral force in the rig due to wind pressure always has a tendency to lean to one side. To prevent it from capsizing, it needs a righting moment (RM) that is stronger than the force applied. It can be understood as a kind of built-in static resistance to tipping and describes the product of the ship's weight and the distance (d) between the centre of gravity (CG ) and the centre of buoyancy (CB). Drift also plays a role, i.e. the tendency to counteract the wind pressure by pushing it away.

In order to achieve the necessary righting moment, there have always been two completely different approaches in the development of sailing boats: While Europe is considered the land of "ballast sailors", where the keels of the ships were designed to be as deep and heavy as possible, the Polynesians in the Pacific built boats with outriggers as proas and catamarans, which was more practical in the shallow island groups and atolls. Instead of weight stability, they favoured form stability. In a monohull, the two centres of gravity CB and CG are close together (drawing above). A slightly heeled keel yacht with a weight of ten tonnes and a distance d of half a metre has a maximum righting moment of five tonnes.

In a catamaran, on the other hand, the centre of gravity moves into the leeward hull under wind pressure due to the large beam. If the distance to the midship line is three metres, the righting moment is already six times as great for a ship of the same weight at 30 tonnes. This means that a great deal of force is required in the rig to tip the catamaran on its side. This is why catamaran masts have a much more stable design and were more elaborately braced in the past than those of monohulls.

However, the heeling curve (see above) clearly shows that once the maximum righting moment has been overcome, the capsizing of the catamaran can hardly be stopped. This point is already reached at an angle of just over ten degrees, i.e. much earlier than with monohull yachts, where the stability initially increases as the heel increases.

Cruising catamarans popular for long voyages

Although they can theoretically (and practically) capsize, cruising catamarans are the favourite type of boat among blue water sailors. Every year, dozens of family crews set off on their Lagoons, Fountaine Pajots, Nautitechs, Outremers and other series-produced catamarans on long voyages across the Atlantic or even around the world. No other segment has experienced such unbridled growth over the past 20 years as multihulls. A boom that is no coincidence.

"Our catamarans are all built to carry their crew around the world in comfort. Even when they get into rough weather," says Bruno Belmont, the leading catamaran developer at world market leader Lagoon - experienced like no other. No one has designed more cats than him, no one has followed the evolution of multihulls more closely than him.

"We have learnt a lot over the three decades," he says, recalling the beginnings with the Lagoon 55, the shipyard's first model. At the time, it was developed by the French regatta boat department "Jeanneau Techniques Avancées" rather incidentally, but marked the beginning of an unexpected success story. "At that time, we still had little experience," says Belmont. "For example, there was no dynamic stability calculation, as is standard for every catamaran today."

When calculating the rig, only the force at which the ship tilts was calculated; the mast and wires had to be correspondingly stronger. "Today, however, most cruising catamarans are designed so that the mast breaks long before the ship capsizes," explains Belmont - analogous to a fuse in an on-board electrical system. The idea behind this is that a cat drifting upside down on the high seas can hardly be righted again; under engine or emergency rigging, on the other hand, it can still reach a harbour. In addition, a new mast is far cheaper than the salvage costs after capsizing.

Just how much safety modern mass-produced manufacturers build into their catamarans can be seen from the fact that their rigs collapse at 40 to 50 per cent of the maximum righting moment. This means that even in rough seas, modern designs can hardly tip over.

They have also become quite heavy due to the stricter strength requirements of the CE standard and the growing comfort demands of customers. "For this reason alone," says Belmont, "they can hardly be levered out of the water."

Reefing according to table

In order not to exhaust the stability and avoid unnecessary risks, it is nevertheless important to "meticulously adhere to the reefing tables, which can be found in every owner's manual."

In the case of the Lagoon 46, for example, it reads: "As the yacht does not heel, it can be over-rigged without this being recognised (...) It is therefore essential to constantly monitor the true wind force and to adjust the sail area to this as a priority."

For those switching from a keelboat, this "sailing by the chart" is unfamiliar. But on a catamaran, there is no feedback for reefing by feel. Even more so than with a monohull: if in doubt, it is better to reduce the sail area too early than too late. A reefed cat sails better than an over-rigged one anyway.

The reaction to gusts also differs. If the wind suddenly picks up or there is more wind in a cloud than expected, there are two ways to temporarily compensate for the overclocking: When sailing courses from half to room wind, it helps to drop as far as possible without risking a gybe. Under no circumstances, however, should you jibe under pressure, otherwise the apparent wind will increase even more.

To quickly take pressure out of the sail, luff up on upwind courses, drop in half to full breeze

On an upwind course, on the other hand, it helps to lean a little, because usually only a few degrees are needed to reduce the pressure. The headsail and main may invert noticeably in the luff, i.e. show a counter-belly. On all courses, reef immediately after the gust has passed!

Bruno Belmont recommends always keeping an eye on the boat's speed in heavy weather and not surfing too fast into the valleys in big waves, otherwise capsizing over the bow is possible, especially with light trimarans.

Capsizing over the bow

With heavy cruising catamarans, there is hardly any risk of being undercut by the waves with the bows and going upside down when surfing. Today's boats have sufficient buoyancy in the bridge deck and in the area of the bows to quickly pull the bow tips back to the water surface when undercut. Capsizes over the bow happen more frequently on trimarans, such as the Dragonfly 28 on the Silverrudder 2015, on fast beach cats or extreme vessels such as the 72-foot America's Cupper from Oracle (see gallery above).

In a storm, Belmont advises setting a small storm jib when running off the waves and slowing the boat down with trailing lines, which he usually lays in long loops from stern cleat to stern cleat. If this is no longer sufficient, he recommends turning under a drift anchor.

He himself has only been scared once on a cruising catamaran, and that was decades ago. Back then, he was testing the prototype of the Lagoon 37 TPI in a severe winter storm. The problem: "The keels were still far too long back then, and we always had the feeling that we were about to capsize sideways." Keels that were too deep were a common problem with the cruising cats of the first generations because they had too much resistance leeward and caused the boats to stumble. For this reason, the windward centreboard is used at most on cats with centreboards in storms.

According to Belmont, capsizes are generally very rare. "We may have missed a few cases," he says, "but to my knowledge, only a handful of the 6,400 ships built have capsized."

So something must have gone wrong in Croatia when the Outremer 45 of a Berlin family capsized during a storm in mid-July. "In the storm, it only took a moment for the boat to capsize," the Croatian rescue team announced on its Facebook page. "But it took four long and labour-intensive days to turn the boat back around."

A well-built catamaran is extremely safe. Only a fire or a cargo ship can sink it

Once a cat is upside down, it is difficult to turn it back again. "One of the most fundamental laws of physics is that everything in nature seeks its most stable position," writes American blogger and catamaran fan David Crawford on his website. And admits: "Once a catamaran is upside down in the ocean, it has found its most stable position." As unfortunate as this is, Crawford also sees the good in it: "For a monohull, the most stable position is at the bottom of the ocean." In his opinion, there is no safer ship than a catamaran. "The most that can sink a well-built cat is a fire or a cargo ship."

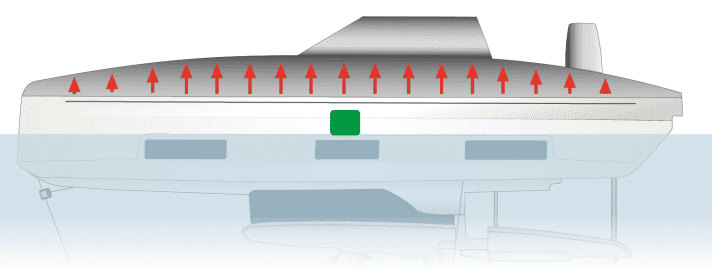

Unsinkable life raft

If a catamaran does go overhead, large air pockets form in the bilge area that is now on top. As long as the catamaran is sealed in the area of the (former) underwater hull, the air cannot escape. The cat can float upside down for many months and is a safe place to wait for help. A capsized Gunboat 55, for example, remained drifting on the Atlantic for 14 months before it was salvaged and restored. The emergency hatches (green) amidships were to remain closed until help arrived. The shipyards often provided U-irons between the hulls so that the sailors could secure themselves with the lifebelts after disembarking.

Where does the bad reputation of catamarans for capsizing behaviour come from?

It is therefore surprising that multihulls still have the reputation of being less seaworthy than keel yachts, despite all their design advantages and technical developments. A few accidents are probably enough to confirm old prejudices again and again. An early report in YACHT is not entirely innocent of this.

On a stormy autumn day in 1968, a test crew capsized on the IJsselmeer with an Iroquois series catamaran and got into serious distress. The editors were still reeling from the shock, so the verdict was: catamarans are not suitable for ocean voyages. After that, they were frowned upon in Germany for three decades.

Burghard Pieske is a man who went on a long voyage with his twelve-metre catamaran back then and had to constantly justify his decision and was even prophylactically thrown out of his sailing club. "The critics were also the reason why we set course for Cape Horn with the catamaran. We wanted to show them," he says.

In his opinion, the question of seaworthiness is not just about the boat, but also about the seamanship of the crew: "If someone knows their boat inside out and knows what it can do, then they can sail safely across the Atlantic, even with a dinghy cruiser," says Pieske. With his "Shangri La", he not only rounded Cape Horn, but even crossed the Atlantic twice in Arctic latitudes.

According to damage statistics, the most common cause of catamarans is not capsizing, but a collision

Nevertheless, catamarans are listed somewhat higher in the insurers' claims statistics and treated separately. "Due to the sailing areas in which they are used and their specific design, sailing catamarans are affected by lightning damage much more frequently than the comparable group of conventional cruising yachts," explains Dirk Hilcken from Pantaenius. Around eleven per cent of all damage to catamarans is caused by overvoltage.

Collisions are by far the most common cause of damage: "Around 32 per cent of damage can be attributed to this. This is followed by groundings and strandings at around 16 per cent." There is hardly any difference between the species. In comparison, however, it is clear "that catamarans capsize more frequently than other yachts, again probably due to their design." According to the statistics, a total of 14 such cases have occurred in the past ten years. "We can say that the general probability of damage occurring in the case of sailing catamarans is around 33 per cent higher than for a monohull yacht," says Hilcken.

Of course, this is not proof of a general safety gap. Nor do the accidents of recent months allow any general conclusions to be drawn. The causes often lie in incorrect use, poor seamanship or external influences, as in the case of a catamaran that capsized in a bottom sea in a harbour approach off Morocco. In such conditions, keel yachts can turn just as easily as catamarans, probably even faster - with the only difference being that one will right itself again and the other will not.