Long voyage: Wind steering system or autopilot - advantages, disadvantages and experiences

Johannes Erdmann

· 24.11.2023

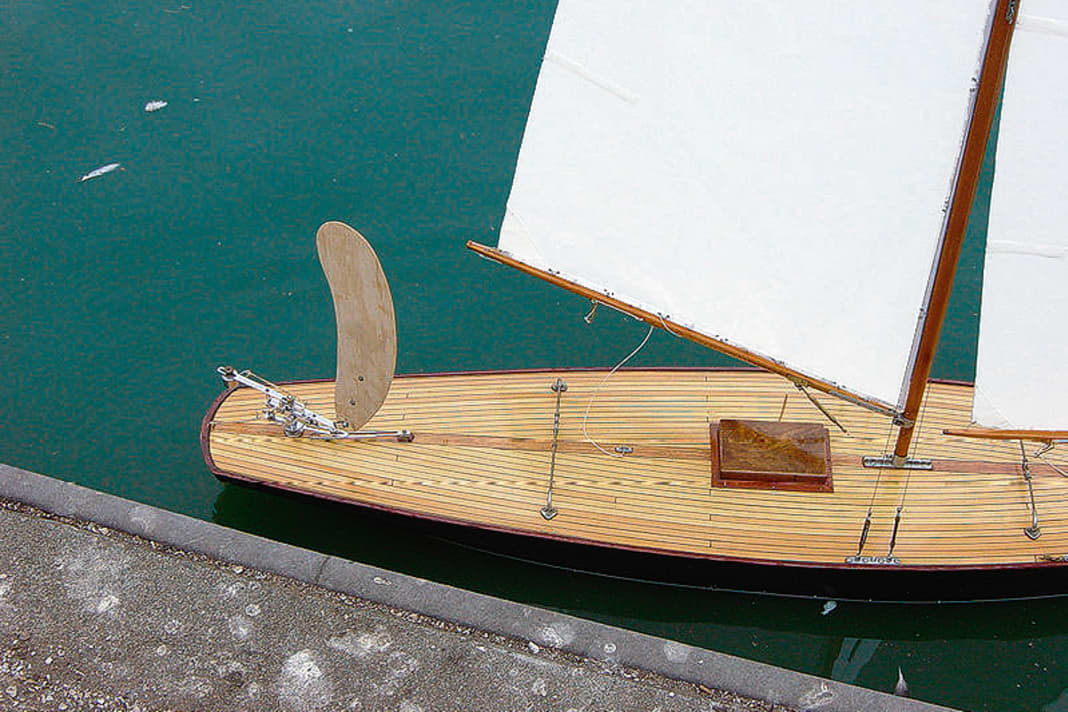

In the past, it was clear that if you wanted to equip a ship for a long voyage or even a circumnavigation, the first thing you needed was a wind steering system at the stern. Similar to the classic millipedes on the shrouds, it was the first step for manytheRecognition signal that a boat is not only intended for the Bay of Kiel, but is ready for long voyages.

There was a reason for windvane steering as a distinguishing feature for real long-distance yachts, as autopilots were not considered reliable enough for long distances at the time. With simple tiller or wheel pilots, the drives were constantly exposed to the weather, and salt water quickly found its way inside, where moisture-sensitive model engines with short-lived plastic gears did their work. Although the systems mounted below deck were protected, they used to be better windscreen wiper motors in terms of their design, which were driven by a bicycle chain on a sprocket on the rudder stock. The electronics were also simple, but power-hungry. The autopilot was given a compass course, which it followed. The course computer only realised that the boat was running off course when it had already passed it. Then the noisy electric motor began to apply the rudder until the boat returned to its old course. It often oversteered in the process. Autopilots were no joy for sailors.

Wind steering systems have their origins in model boats

The wind vane has always represented an extreme contrast to the autopilot. If the ship veers off course, it bobs slightly with the vane and silently turns the rudder, bringing the ship back on course as if steered by a ghostly hand. You can watch her do this for hours. She has a calming effect.

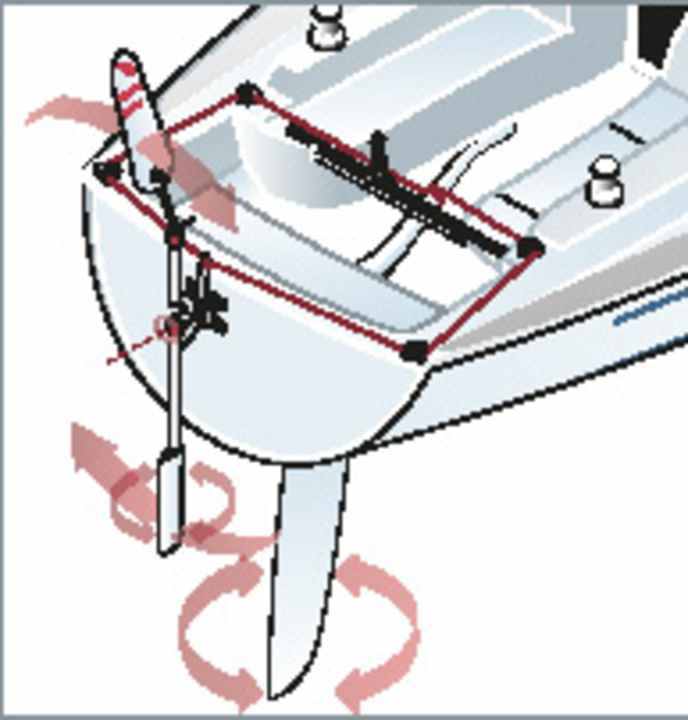

The system was developed almost 150 years ago for model sailing boats, when remote controls were not yet available. A small wind vane was mounted on the stern of the model boat and connected to the rudder stock via two gear wheels. If the vane is set to a half-wind course and the model boat then drops to a space-wind course, the wind vane sets the rudder via the cogwheels so that the boat returns to the old course. In this way, a ship under wind vane always steers a slight lurching course, but reaches its destination. The system was later fitted to yachts, and since the 1960s has also been built in series and modified with a pendulum rudder, which generates even more steering force than the vane alone.

The wind steering system keeps the boat at exactly the same angle to the wind

Of course, windvane steering has always had some disadvantages in terms of function. For example, the cumbersome commissioning (compared to the autopilot) and the fact that if the wind direction changes, the boat continues to sail at the same angle to the wind, but then no longer to the correct destination. This is a drawback in areas with constantly changing wind directions. But not a problem on long journeys in a steady trade wind. There, the yachts reach their exact destination, as the case of single-handed sailor Derk Wolmuth proves: he had to disembark from his Vindö 40 in the Pacific due to illness, but adjusted the monitor wind steering system on his yacht beforehand. Four days later, the boat reached Hawaii completely autonomously.

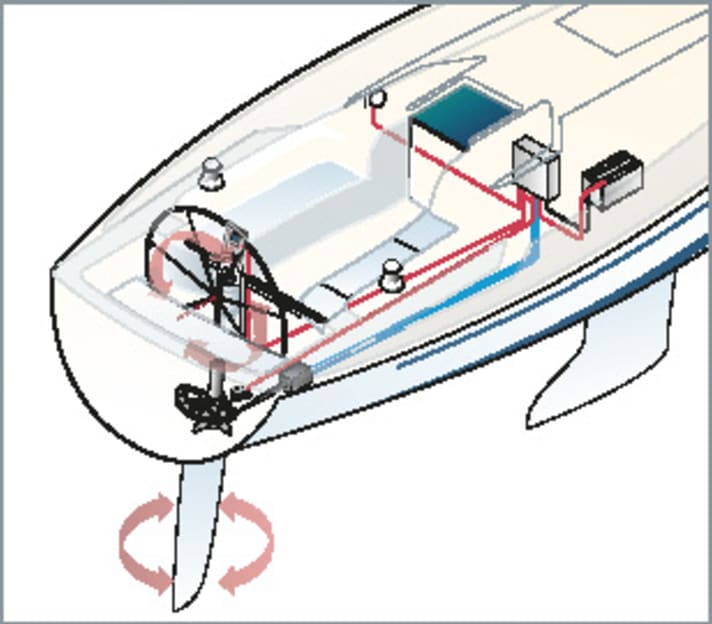

In the meantime, however, the technology has developed fundamentally. Autopilots no longer require as much power as they used to, and the drives hardly cause any problems. Operation is child's play: the boat stays on course at the touch of a button. Thanks to gyro sensors, it no longer needs to go off course for the autopilot to react. The modern systems recognise when the boat has a tendency to run off course due to a wave - and work against it before it happens. Autopilots can also steer by wind direction, not just by compass. Thanks to new solar panels, mobile fuel cells or hydrogen generators, even energy problems are a thing of the past. As a result, yachts can now sail long distances at sea and around the world without any wind steering system.

Can you go on a long voyage without a wind steering system?

In February, YACHT published a contribution with the question of whether wind steering systems still have to be attached to the stern of a blue water yacht.t, which generated a storm of comments. Fans and advocates of wind steering systems bristled at the idea that someone could go on a long voyage without a wind vane, speaking of negligence.

A survey on Instagram revealed that two thirds of the sailors surveyed there still believe that you shouldn't set off on a long voyage without a wind vane. Only a third believe that autopilots are mature enough.

What long-distance experts say

Every season, Philipp Hympendahl cruises long distances through the North Sea and currently on the Atlantic with his "African Queen". His Windpilot Pacific is the best helmsman for the single-handed sailor: "I am always impressed by the silent and harmonious mechanics with which this great device steers my boat, even in strong winds. For cruising sailors and those who value safety and reliability, a windvane is indispensable, at least as a backup," he says.

Andreas Haensch, 78, and Andrea Fuchs, 71, have been travelling long distances on their Hallberg-Rassy 42E "Akka" since 2006. Although the crew have a Raymarine autopilot, they are real fans of the Windpilot Pacific Plus, a wind steering system with auxiliary and pendulum rudders: "For two reasons: It steers us without consuming energy and can even be used as an emergency rudder if necessary," says Fuchs. At the time of their voyage preparations almost 20 years ago, lithium batteries were not yet in sight, so there was no question of relying solely on the electric autopilot. "I don't think it would be any different today, though. We are simply more traditionally minded. For us today, the choice of boat might even depend on the possibility of being able to install a wind steering system," adds Fuchs. Under Windpilot, the main rudder of their "Akka" has been determined; the wind steering system works as an independent system. "We found it very convenient to take the strain off the main rudder on long journeys," she says. In light winds, when the steering impulse on the windvane is not sufficient, the couple used a tiller pilot mounted in the windvane.

Wind steering system or not - that's a question of faith. With my boat, only an off-centre installation would have been possible. So I orientated myself on the skippers in the Vendée Globe - and they all sail with electric autopilots" (Martin Daldrup, "Jambo")

Dieter Blass, 75, from Lübeck also chose a wind steering system when equipping his Amel Sharki for a circumnavigation. "The Amel already had a powerful built-in pilot of the fishing boat type from the shipyard, but it was too imprecise for me," says Blass. Due to the centre cockpit, it was awkward to pull steering lines from the stern to the wheel on the Amel, and Blass also opted for a Windpilot Pacific Plus. "I've never regretted the decision and spending 6,000 euros," he says. The mechanical system only failed once, when he turned round on the way to the Caribbean due to strong winds. "When we wanted to set sail again, there was no more pendulum rudder. The shearing forces from throwing the stern around must have broken the aluminium rudder." Fortunately, Blass had a replacement with him. After that, there were no more problems. "It's often different with autopilots. We met a couple from Munich in Panama who used one autopilot per day on their onward journey and finally had to turn back after three days."

Not all ships have space for a wind steering system

However, it is difficult to install a wind steering system on some types of ship. For example, if a centre mounting would block the bathing platform or the stern of the ship cannot absorb the forces of a wind steering system without major reinforcement measures. Wind steering systems have natural limits on particularly large boats or catamarans.

"Both are wrong, because the Hydrovane is even installed relatively often on large to very large ships and cats, precisely because it is also an emergency rudder," says Thomas Logisch, who has been selling the Hydrovane wind steering system in Germany since 2010. The system is a classic auxiliary rudder system that builds up power through the wind vane without a pendulum rudder and steers the boat with its own rudder. Unlike pendulum and double rudder systems, the Hydrovane can therefore be mounted off-centre if a bathing platform is to remain free at the stern. However, there are, of course, physical limits to such a solution, because if the system is mounted far outboard on a modern wide stern, the boat must be sailed extremely upright and, in case of doubt, even reefed so that the wind steering system rudder does not deflect.

Under such conditions, the system can steer a boat to its destination in an emergency - but it is not a fully-fledged solution. Otherwise, yacht designers could simply screw the main rudder to wherever there is space. If necessary, a catamaran can sail to the next harbour with just one rudder after losing a rudder, but not with the same performance.

The wind steering system as a backup for the autopilot

There are a large number of long-distance sailors who simply screw a windvane steering system to the stern to have a kind of insurance on board, but rarely use it. "I only had the windvane steering system with me because you always read in old reports how important they are," says Turan Jenai. In the winter of 2017, he sailed his Oceanis 373 from Italy to the Caribbean. "But I mostly just used the autopilot," he says, "in the end, the wind pilot was just a backup for me." Klaus Rathjen from Hanover is currently looking for a new boat and has set his sights on an RM 1070. "My gut tells me that a wind steering system would be a good thing," he explains, but he raised the issue with the RM and Pogo shipyards at the Düsseldorf boat show. "In both cases, we were told that a wind steering system would no longer work here."

The new long-distance sailors rely on autopilot

The new generation of long-distance sailors relies on modern autopilots. "On my Bavaria 34 Holiday, a windvane steering system could only be fitted off-centre because of the bathing platform," says Martin Daldrup, 59. "How the forces could then have been absorbed at the transom ... that was too complicated for me. That's why I opted for an electric autopilot and modelled it on the big regatta sailors. In the Vendée Globe, they also sail electrically, and the required power is generated by a trolling generator, which I also had."

Tim Hund, 25, from the "sailing boys" also opted for an electric helmsman: "I find the wind steering systems expensive and complicated to install. They also take up the whole stern." But he also sees advantages: "What's cool, of course, is that they don't use any electricity."

For Frank Winkelmeier with a First 35, the case is even clearer: "My opinion of mechanical self-steering systems is the same as my opinion of analogue photography: it used to be great, but nobody needs it anymore. After all, the power supply is no longer a problem thanks to hydrogenerators and solar power," he says.

Mechanical or electrical is also a philosophical question

Whether to have mechanical or electric steering - "that's a philosophical question," Daldrup categorises, "and we mustn't forget that those who frequently speak out are not a representative cross-section of sailors."

There are few sailors who have had as much experience with both systems as Uwe Röttgering. The 55-year-old first sailed over 50,000 nautical miles around the world with his aluminium yacht "Fanfan" and an Aries wind steering system and then converted to a Raymarine autopilot with linear drive. "My personal eye-opener was the Twostar 2017, which I took part in with a Class 40," he says. "During this transatlantic regatta, the field got caught in a storm with up to 50 knots. We only let the yacht run away from the wind and sea under headsail."

My eye-opener was a storm on the Atlantic. We ran the Class 40 under headsail and autopilot. She was surfing at up to 20 knots. Completely without any tendency to go sideways" (Uwe Röttgering, "Rote 66")

He programmed the autopilot to hold a compass course in order to prevent course changes due to a changing wind angle when surfing down the waves. Röttgering manually set the intensity of the rudder deflections to the maximum value. "With this setup, the yacht often surfed down the waves at over 20 knots without showing the slightest tendency to break away or even cross. This would certainly not have been possible with a wind steering system - even on a cruising yacht."

Nevertheless, Röttgering does not believe that the age of wind steering systems is over: "For long journeys, I would equip a cruising yacht on a tight budget with a pendulum rudder system that acts on the main rudder," he advises, "and possibly also a tiller pilot or a wheel pilot for light winds or motorised sailing." However, if the on-board budget is better filled, he would always opt for an electric autopilot with hydraulic linear drive and gyro sensor. "Plus the identical system as a backup, which preferably has no network connection to the other system."

Pros & cons of wind steering systems

Advantages

- Less susceptible to faults

- No power consumption

- Works almost silently

- Simple installation if a tiller control is available

Disadvantages

- Steers only according to apparent wind

- Is not suitable for fast, steering-sensitive yachts such as modern cruisers/racers

- Pendulum/double rudder creates additional water resistance

- Steering accuracy often low in light winds. Sailing under spinnaker or gennaker often problematic

- Precise steering requires good sail trim. Often the mainsail has to be reefed earlier to achieve the correct trim, resulting in a loss of speed

- In gusty winds, larger course deviations (+/- 20 degrees) occur

- Commissioning is complicated and takes some time (attaching and tensioning the steering lines, trimming the yacht, etc.)

- Often blocks the bathing platform. Davits cannot be used

- The system is exposed at the stern, so there is a risk of damage to some components when manoeuvring in narrow harbours

- Risk of damage to the pendulum rudder from floating debris

Pros & cons of autopilot

Advantages

- Can steer according to true and apparent wind and compass course

- With gyro systems, extreme control accuracy on all courses

- Follows the set course precisely at the touch of a button

- Hydraulic pilots have an extremely short rudder setting time

- Can be operated from anywhere via radio remote control

- Uncomplicated commissioning (important when sailing short distances)

Disadvantages

- Technically more fragile than a wind steering system, spare parts may have to be transported to remote locations at great expense

- High power consumption, which makes it necessary to upgrade the power supply (solar, fuel cell, second alternator)

- Higher costs and sometimes complex installation

- For safety reasons, an equivalent electrical backup system should be installed for long journeys, which incurs double the costs

- Sometimes quite loud, depending on the installation

- Tiller pilots are wearing parts on yachts of around eight tonnes or more on long voyages, not least because the gears are often made of plastic. They also have a long rudder setting time

Development of the wind control system over time