Sailing along the Adriatic once, from north to south and back again: Slovenia-Montenegro-Slovenia, that's the simple plan for the trip. One week, a good 650 nautical miles, and only one stop halfway. It sounds a little frivolous, especially in winter, which can be frosty even in the south and particularly nasty in the bora. On the other hand, the boat, whose log has not yet counted 30 miles, is a promise.

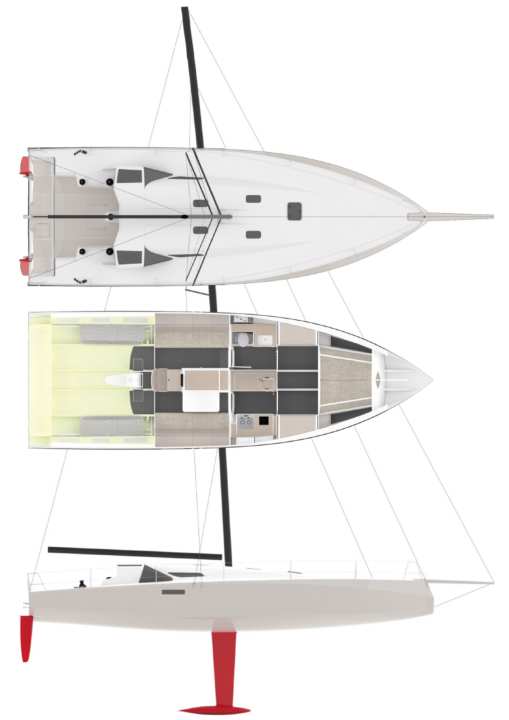

Antoine Cardin and his colleagues at Judel/Vrolijk & Co in Bremerhaven have put all their skill, passion and enthusiasm into this design - a yacht unlike any other currently on the market: 80 per cent Class 40, 20 per cent cruising boat, perhaps 70:30 or 90:10 - only time will tell.

In any case, she has diesel-powered hot-air heating and almost everything else to keep the crew happy and energised on long voyages: eight berths, a galley, wet room, navigation and a saloon in which even ten people would not feel cramped.

But there are only four of us, so we are sailing the J/V 43 two-handed in a waking rhythm. And we are on board not so much because of its comfort features, but because of its performance potential, which exceeds all conventional standards.

J/V 43 is hardly comparable with any other series boat

The yacht weighs just half as much as conventional performance cruisers of its length. Nevertheless, she carries more cloth on her filigree carbon fibre mast: 125 square metres on the wind, more than twice as much on the beam when the large A2 is standing, an asymmetrical spinnaker with an area of 210 square metres alone.

The production boat that doesn't come close, but still comes closest, is the Pogo 44, but even this displaces 20 per cent more: 6.3 instead of 5.2 tonnes - that's worlds apart, especially as the hull shape and cockpit ergonomics also differ greatly. A difference like that between an SUV and a super sports car.

With its sail carrying capacity of 6.5, the J/V 43 is head and shoulders above anything the civilian shipping market can offer. It is only equalled by the professional ocean racing of the current Class 40 generation. Right down to the first decimal place, she resembles a thoroughbred Pogo 40 S4 that is completely empty below deck, such as the "Sign for Com" by Lennart Burke and Melwin Fink.

That's how she looks: broad-shouldered, athletic, but at the same time wiry, even delicate with her hull sides tapering sharply towards the deck and the light, almost floating stern. Only the cabin superstructure that extends to the foredeck and the side windows set her apart visually from Class 40 racers. However, all of this is so smoothly integrated stylistically that you have to look three times to even notice the differences.

Raw, functional aesthetics

As she comes alongside to clear out at the Piran pier, she looks like a UFO from distant galaxies compared to the other cruising yachts moored further inland in the dreamy old town harbour. Her raw, functional aesthetics exert a charm of their own, especially as the white hull contrasts impressively with the gloom of an approaching warm front. Even in the evening drizzle, the sight still attracts the curious. "Ahhh, regatta!?!", surmises the harbour captain during his inspection tour. "No, cruising!" replies the owner, pointing into the cabin illuminated by concealed LED strips. When the captain frowns, he corrects: "Almost cruising!" Both nod. "Very fast," says the official. Then that's settled.

However, the start is rather slow. The wind was initially only six to eight knots from the north-east. In order to get away from the coast and the small fishing boats, we motor-sailed flat off the sheet only under main to the south-west. This is not the J/V 43's speciality.

The insulation of the Yanmar diesel has also been sacrificed in the endeavour to leave out everything that doesn't make it fast. It stands in the centre of the saloon, encased in lightweight sandwich panels with a foam core, which are also used to laminate the rest of the interior. There is no insulation on the inside. Too heavy, according to designer Antoine Cardin, who was already struggling to keep to the maximum weight of just 250 kilograms that he himself had defined for all the fittings and comfort accessories. The plywood bulkheads alone weigh that much in large-scale production.

Start with handbrake

At 2,500 revs, the three-cylinder consequently rattles with the vehemence of 85 decibels, close to the limit of hearing damage. Only jackhammers and chainsaws make a more brutal noise. In the cockpit, however, the sound pressure is reduced to a tolerable level. The boat runs at a good 6.5 knots at cruising speed when there is no wind at all; it is around seven knots for the first few miles with a slight push from aft. And you can marvel at a phenomenon that is unique.

In the rhythm of the swell, which comes from a fresh south-westerly off the Italian coast, the current at the transom repeatedly breaks smoothly for a second or two. It is the first indication of the J/V 43's ability to switch from displacement to planing extremely early - the Holy Grail of modern performance yacht building. And it never gets boring to follow the quiet spectacle in the wake in the days that follow.

It makes up a little for the slow start. Actually, we had envisaged a double-digit speed through the night. One change of watch to Kvarner, the inlet south of Pula, that's how we had imagined the journey, two more to the Kornati islands, Montenegro in two days at most. It was not an illusory expectation. The Class 40's 24-hour record is 428.8 nautical miles.

Of course, the changeable weather demands patience and humility from us - and repeated extra shifts for the engine, which cause the level in the transparent 60-litre tank to dwindle so much that we take the precaution of topping up the reserve canister south of Split.

Sailing behaviour: from walk to trot and immediately into extended canter

In between, however, the J/V 43 is able to show off its remarkable capabilities several times. She doesn't need much to do so. When the breeze slowly sets in on the first night further out at sea, first with 3 Beaufort, later in a front with a good 5 Beaufort, she switches from walking to trotting and immediately afterwards to a stretched gallop.

Before it really starts to bang for the first time, she is already running at a steady nine or ten knots at ten to twelve knots from the east with only half the wind under genoa and main. Ahead, the voluminous bow occasionally rumbles into the sea, while aft nothing remains but two strips of the rudder blades, illuminated by the pale moonlight, and a gentle foaming of the Adriatic Sea, which emerges behind the stern as if freshly ironed. It feels like magic, as if we were sailing across the sea on a magic carpet: gentle, weightless, fast.

As we cross the Kvarner Bay, the wind picks up and curiosity wins out over tiredness and clammy bones. A few minutes later, the gennaker goes up, followed shortly afterwards by the pressure in the air. The boat transforms again, this time into a hungry beast eager to devour miles.

The NKE displays jump from twelve to 16, to 20 knots of wind, and the log follows almost in real time. The 18 can be seen briefly, never less than 15 knots through the water. The explosion in performance is so sudden that you have to recalibrate your own perception.

The full bow corresponds to the current state of the art in ocean racing

In the well-protected cockpit, shielded by the overhang of the cabin roof, the crew ducks away from the spray, which is now flying horizontally. The helmsman, however, sits more exposed, unless the autopilot is steering. Although the scow bow never undercuts, it sometimes shovels hectolitres of green water aft along the cabin superstructure with its bevelled edge towards the foredeck. At the tiller, it is almost impossible to avoid this power and mass, so you should always be well-pitched. Because behind the traveller, the coaming jumps downwards, and anyone who loses their footing there ends up half a metre later in the stream.

The baptism of fire is repeated even more impressively on the second night. We sail for hours between Primosten and Trogir, slaloming through thunderstorm cells that build up off the coast. Flashes of lightning and weather lights illuminate the huge cloud towers from below. And just when it looked as if we would get away unscathed, all hell breaks loose in a squall that brings 35 knots of wind, hail and a new top speed: 21.2 knots, only with a double reefed main and small jib.

It is merely an indication of what this boat will be capable of once it has been extensively tested, sailing on the open sea instead of on a cruise, when the system of six individually fillable ballast tanks, which cannot yet be used during the trial run, helps to improve the trim.

In any case, the first impressions impressively prove what the figures already suggested: that the J/V 43 is travelling in a dimension all of its own, limited more by the skills of the crew than by the laws of physics, which it seems to be able to override effortlessly.

The whims of the weather put the brakes on

The fact that it ultimately takes three days from Piran to the glamorous Portonovi in Montenegro is only due to the vagaries of the weather. But that changes fundamentally one night and a few hours later when we start our return journey.

A heavy storm from the south-west blows us two thirds of the way back to Istria. It gets wet and bumpy with waves of up to two and a half metres and winds of between 18 and 28 knots. Now the time matches our original expectations. If you exclude the diversions and the waiting time for clearing in, the J/V 43 manages the 270 nautical miles to Mali Losinj in just over 20 hours.

In summer, the island is one of the favourite destinations of Adriatic sailors. We choose it as a stopover because the following day a Bora will bring up to 60 knots from the north-east - too much to cross the Kvarner, which acts like a jet for the cold air from the mountains. Once again, our yacht becomes an attraction for the locals. Nobody else goes sailing at this time of year, especially not in such rough conditions. Radio Split has been tracking us via AIS and radar and has already announced our arrival to the harbour captain, who actually accepts our mooring lines on Saturday evening.

Within a few minutes, the J/V 43 is transformed below deck from an organised functional space into a casual hang-out. The bags, which are usually wedged between the engine box and the port sofa, move to benches and the foredeck. Because there are shelves and open swallow's nests, but no cupboards, stowing requires a certain amount of shirt warmth.

Transformation of the J/V 43 into a cruiser

Fully occupied with eight crew members, this would inevitably lead to chaos. But with four people, sleeping bags, clothes, life jackets and headlamps get lost in the wide saloon. The Eberspächer heater pumps dry, warm air into the room under the companionway on the starboard side. The light strips under the cabin roof, switched from white to red, create a cosy atmosphere, and with the first beer in the sudden silence on the jetty, there is simply nothing missing to make you happy.

Well, the cushions are only 40 millimetres high - the weight, you know. With the exception of the wet room, none of the rooms have doors and therefore offer anything like privacy. The owner couple shares the foredeck with its XXL berth with the huge sail bags. And if you want to make yourself comfortable on the tubular bunks, which are located under the cockpit floor on both sides, you have to wriggle past the pipes and stopcocks of the ballast tank system first. Compared to the enormous sailing potential of the J/V 43, however, the compromises in comfort are hardly worth mentioning.

The format also helps here. The fact that the boat is one metre longer than the class to which it is geared not only creates more buoyancy to compensate for the weight of the extension, but also the necessary space for cruising without compromising the lines.

However, it is difficult to quantify how much racer and how much cruiser it contains. It varies depending on the intended use and perspective. On deck it is fascinatingly demanding, below deck it is unexpectedly comfortable despite its functional crudeness.

Moulds of the J/V 43 are designed for a small series

Why this boat? The owner of build number 1 and co-initiator of the small series sees it as "the next generation racer-cruiser - a boat for unfiltered sailing fun". Wind transforms it "immediately into speed". Below deck: "not a cave, but a real living space".

But you still have to want it. The three metre draught. The roaring diesel. The lack of any cleats to tie up the mooring lines. And the strength and effort it takes to keep such a thoroughbred running. And on top of that, such a precision tool costs more than an off-the-peg performance cruiser - a good one and a half times as much as a Pogo 44, to name just one example.

One harbour day later, the wind is still gusting at 45 knots on the northern Adriatic. We prepare the third reef in the main, lash the genoa to leeward on the foredeck and set the working jib, which is attached to a removable textile stay. The wind comes from the north-east and we sail the first 40 nautical miles on a north-westerly course, almost 30 of which are without cover in the unbraked bora.

Half-wind courses are the parade discipline of scow-bow constructions. In the lee of Losinj and the offshore islands, the J/V 43 panthers off as if unleashed: despite the small canvas, she logs 15, 16, 17 knots. However, the sea ahead on the Kvarner is foaming, and the storm is blowing the water horizontally off the three or four metre high wave crests. So, what do you say to an unrestrained blast at the end of the first extensive maiden voyage?

Following good seamanship, we furl the jib in good time. With the main reefed three times, the boat sails as if on rails, with low rudder pressure and still travelling at nine to ten knots. The good spirits at Radio Split, who are no doubt watching us on their monitors again, need not worry. But there is a growing desire among the crew to do it again as soon as possible. The plan is to start in the spring.

Technical data of the J/V 43

- Fuselage length/LWL: 13.10 m/11.52 m

- Width: 4,50 m

- Depth: 3,00 m

- Mast height above WL: 19,80 m

- Weight/ballast/proportion: 5.2 t/2.1 t/43 %

- Sail area downwind/STZ: 125 m²/6,5

- Engine (Yanmar 3YM30): 29 PS

- Contact: info@judel-vrolijk.com

Other special boats:

Jochen Rieker

Herausgeber YACHT