- Associations from the power trip of heavy yachts through the sea

- Knowledge and skill count for success, not physical strength

- From then on, sponsored, knobbly "mini-twelve" appeared everywhere in Germany

- Looks like a model boat, but demands the whole sailor

- Ulli Libor, two-time medallist in the Flying Dutchman, is president of the class

- The class wants to get out of the niche - all the way to the Olympics

- Technical data (Charger version)

It's amazing how much the view of the world changes by just a few degrees with a simple change of perspective. When it feels like the jetty is at chin height when mooring and casting off and no one can jump up quickly and rush somewhere to hold the boat or clear fenders and lines. It also quickly becomes apparent on board that it makes no sense to always kick everything full throttle; a gentle tap with the balls of your feet on the steering pedals is usually enough. Welcome to a 2.4mR "yacht", the boom boat of the German class landscape, the unique "inclusion boat" that can be sailed by everyone with a chance of success and guaranteed fun: old warhorses, dinghy freaks, "disabled" people.

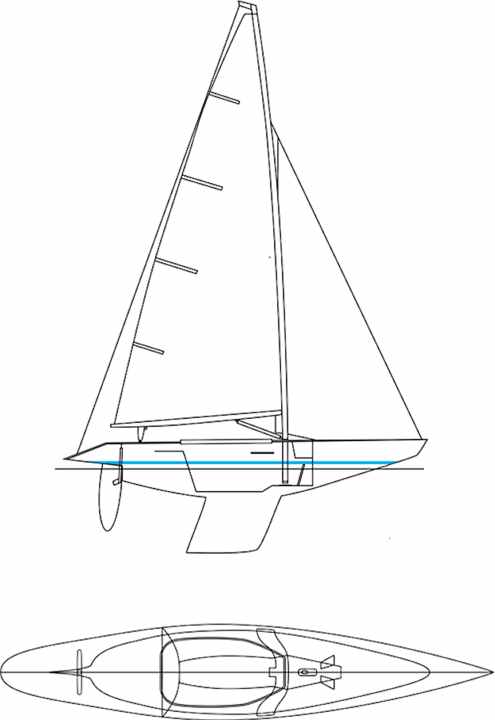

A 2.4 is a - usually foot-steered - true metre-class yacht, a small twelve, so to speak. And it sails accordingly, life begins at 30 degrees. But it also sails lean. Because a 2.4mR ship looks good. Typical: the flat silhouette under foil sails and the long overhangs of the 418-centimetre-long hull. Also typical: the trim sensitivity when the boat is in position and working close to the water. To prevent this from becoming a danger, the boats are equipped with breakwaters and buoyancy sensor-controlled bilge pumps.

Also interesting:

The small keelboat really keeps you on your toes, especially mentally - because everything goes much faster than on large boats and nothing, not even the smallest gust, can cause a surprise. It's pure concentration on sailing. A complete tack takes maybe three seconds (including a 60-degree change of heel), and the mainsail can be flapped from "too tight" to "completely open, fluttering" in half a second at most. It's unusual that the feet are mainly responsible for manoeuvres - and that the hands remain free for clicking the clamps and pulling the ropes. On other boats, someone does one or the other or someone steers and operates everything with their hands.

Associations from the power trip of heavy yachts through the sea

The 2.4 is a wonderfully tactical and sensitive craft that provokes age-old sailing and racing reflexes in regattas. However, simply chilling out with the small boat is fascinating enough. And leaves sailors pleasantly confused. Because priorities have to be reorganised. For example, "retract your head when manoeuvring" is an automatism. However, this is not necessary here because nothing can happen and moments of fright only confuse the foot control. The only thing that can be lost is orientation due to the rapidly changing heel and the low visibility. In this sense, a 2.4 is more of a mental challenge than a physical one.

If something doesn't run smoothly, it's usually because a tense body stiffens in the heels and then nobody is actually steering. And the boats turn well, virtually on a disc. After all, they are small keelboats that have a lot of momentum.

2.4s do not have spinnakers. But nobody needs them there either. The unfurled genoa replaces it as on the Star boat, and the complex mast-folding manoeuvre is similar: an outhaul (with an "inhaul" line to the clew) shoots from the main boom to windward, the backstay shoots off, at the same time a line pulls the rig forward in the deck, the forestay now hangs through like a washing line.

The bulbous power headsail pulls the small craft into wave troughs and the rudder sensitivity comes into its own. In windy conditions, a real long keel displacement wave rushes alongside the stern and makes steering a major task. When does the boat turn or tie up and how? Pedalling a 2.4 downhill evokes associations with the power trip of heavy yachts through the sea, ships about twenty times the size. A train of thought that is quite obvious, as Frenchman Damien Seguin recently proved at the Vendée Globe. It goes without saying that the Frenchman has raced around the world without restraint in his 13-year-old Finot design without foils. But the fact that he has already won two Paralympic medals in the 2.4 and is multiple world champion in the class perhaps does. And without a left hand.

Knowledge and skill count for success, not physical strength

A master of his trade has ensured that the mini metre yacht is sensitive enough to react to even the smallest waves. But who is that actually? Peter Norlin. A good friend of his was once seriously injured in a car accident. Norlin, then a kind of king of six-metre racing yachts, drew a rather ingenious boat in 1983 that fitted into the metre class measurement and at the same time was absolutely up to date in terms of regatta technology - and it could be steered with the feet. Norlin later revised the hull lines of the design for the class and set them in stone; they are still valid today.

So Norlin's friend was able to sail again, and a class was born that would soon have international and Paralympic status and would also compete together at Kiel Week - and a sailing method called inclusion. Inclusion is one of the most ingenious social developments of our time. It simply means "inclusion" and therefore the opposite of "exclusion". Inclusion affects far more people than definitions suggest, because it is about sailing qualities beyond a standardised physique. Physical characteristics are always the crux of success in a class; the absence of a certain physique leads to a technical knock-out. The fact that this constraint does not exist in the 2.4, but only knowledge and skill count, is a wonderfully liberating feeling. "Containment" is therefore one reason for the unusual popularity of the boats, which are even sponsored as a class. And which has a strong protagonist: Heiko Kröger.

He is not only ten-time world champion in the 2.4, gold and silver medallist at the Paralympics, but also something of a forefather of the boom in Germany and virtually synonymous with the class in this country. There will probably never be a more specialised specialist for this type of boat. However, his love affair with the 2.4 started more by chance in Gelting and led via Berlin. Kröger sailed a Laser-DM on the Baltic Sea in the early nineties. And back then, someone towed in a joke of a German "mini-twelve".

From then on, sponsored, knobbly "mini-twelve" appeared everywhere in Germany

In 1981, a group led by shipyard boss Michael Schmidt, the designers Judel/Vrolijk and YACHT editor Erik von Krause founded an America's Cup syndicate. And it is said that during the Admiral's Cup, Schmidt discovered the small, foot-steered, one-man seat gag boat "Illusion", designed by Jo Richards, which resembled a twelve-man model and was intended for advertising purposes, in the harbour of the Cowes venue with his "Düsselboot". And thought: "We can do that too." From then on, sponsored, knobbly "mini-twelve" boats appeared all over Germany to promote the Cup idea. This was also the case in Gelting, where Kröger sat down in the Jux box and did lap after lap - just for fun. Kröger just thought "I hope it doesn't get dark so quickly."

However, a "mini-twelve" has almost nothing in common with a 2.4mR boat. The former is a simple fun boat with shrouds bolted to a beam, the latter is something to be taken very seriously (one metre longer and narrower in relative terms). And Kröger wanted to be taken seriously; after all, the boats already existed in many countries and world championships were held. But there was no exchange or international class - just a building kit from Finland without instructions.

There was only one person who could help Kröger: Bernd Zirkelbach from Berlin, Germany's most successful sailing coach and later team manager of the German Paralympics team, a mixture of Jogi Löw and Miraculix. Because of a Paralympics test, Zirkelbach was invited to the 1996 World Championships in England, from where he brought two boats with him, "Max" and "Moritz". He still competes with "Moritz" today and regularly sails into the top five at championships.

Looks like a model boat, but demands the whole sailor

This is how Kröger got his 418-centimetre-long dream yacht. He proudly showed it round and round to a crowd of people in Strande who wanted to know: "What is this thing?" Nobody had ever seen anything that looked like a cross between a model boat and a modern six-metre racing yacht.

That was the beginning, and not so long ago. Today, more 2.4mR boats meet on the Alster at the YACHT event than there were in the whole of Germany back then. In the meantime, sailing - and therefore the 2.4mR class - is no longer a Paralympic discipline. But the class is still firmly in the saddle because it embodies the idea of inclusion and at the same time offers high-tech. And it continues to make a name for itself with generous campaigns like this one.

The "training" on the Alster continues. Ex-contender and 505-racer Olli Thies starts as a gate-start pathfinder from starboard, the others pass behind his stern. Sailmaker and bard Frank Schönfeldt seeks his luck on the extreme right bank of the Alster - contrary to his popular song "all alone on the left". Meanwhile, dragon ace Peter Eckhard sails a strong cross. However, only the heads of the actors can be seen above the three-cheese-high freeboard.

Because the 2.4s are semi-long keels, which are also often sailed by dinghy freaks, Ollie's unusual boat is called a "lead transporter". The borrowed "Whippersnapper XXS" ("little smart arse") turns out to be fast; no wonder, as it once belonged to the world champion from England. Thomas Jatsch, who sails on the boat himself, is the hire company, surveyor, dealer and one of the engines of the class: Since the Paralympics cancellation, the sponsorship of the official Royal Yachting Association (RYA) amounts to exactly zero euros. That's why there are excellent but almost unsailed boats on the island. Technik-Thomas trades them. He sold one to Frank Schönfeldt. He commented on the photo confirming the shipment and delivery date: "Just three more sleeps", as excited as a child before Christmas.

Ulli Libor, two-time medallist in the Flying Dutchman, is president of the class

The end of the regatta is approaching, as is the jetty. Once again, classic seamanship is required when mooring. After all, quickly stopping the engine or tearing down the sails is out of the question; and we are still dealing with a real keelboat whose mass pushes. And from the ant's perspective, stern piles become over-man-high obstacles that protrude from the water like lighthouses.

How good that Thomas has deployed fenders at the edges of the jetty: Sheer the boat slowly against the wind and secure it. Only then do they rise from the manhole and roll onto the jetty, usually upwards. Nevertheless, the small boats need the same infrastructure as the large keelboats, crane, cradle, trailer and more.

For a few years now, none other than two-time Flying Dutchman medallist Ulli Libor, 84, has been president of the class. And things have been going well ever since, and not just in sporting terms. A welcome development, because "unfortunately the boats used to lead a niche existence," remarks Zirkelbach. But Libor is attracting strong sailors by the dozen. Frank Schönfeldt may be the latest prominent newcomer - but he is far from the only one. Photos from the German Championship show him in a starting duel with FD specialist Heiner Forstmann, with Kalle Dehler in second place. Schönfeldt said that he had "never come back from a regatta so grounded".

However, Libor is concerned about more than just the size of the fields in 2.4mR regattas - it is the image of a "disabled boat" that comes at the expense of an "inclusive boat". Libor has already witnessed unpleasant exchanges between top sailors and renowned club bosses because of this. Preserving one and doing justice to the idea of inclusion at the same time are two different things.

The class wants to get out of the niche - all the way to the Olympics

But inclusion or not, the boat levels out every nuance, no refuge is like this one. Thomas Jatsch puts it in a nutshell: "You can finally be who you are." Incidentally, his boat is asymmetrical because the left-hand side sometimes doesn't want to be like him. Sometimes there are also mini-pins. For everyone, just the way they are.

And for many, that is the greatest gift. The medical description of what "disables" world champion Megan Pescoe, for example, makes nasty reading (neurological muscle problem). But, hey, world champion! Plenty of normal people and men wiped off the board. You have to be able to sail for something like that.

The German class association is now the largest in the world. Libor even harbours hopes for the Olympics. But not necessarily as part of the Paralympics; despite high hopes, sailing was not reinstated as part of the Para Games. But as an individual discipline. Because the central argument is absolutely watertight and irrefutable: a sport in which people of all conditions - male, female, heavy, light, "disabled", normal - compete against each other on an equal footing simply does not exist. The 2.4mR yacht therefore occupies this niche on a world-exclusive basis, spanning all types of sport.

And the scene is rightly quite proud of this.

Technical data (Charger version)

- Designer: Peter Norlin

- Type: Metre class yacht

- Building material: GRP

- Torso length: 4,18 m

- Width: 0,81 m

- Depth: 0,99 m

- Weight: 265 kg

- Ballast/proportion: 180 kg/86 %

- sail area: 7,53 m2

The article first appeared in YACHT 05/2021 and has been updated for the online version.